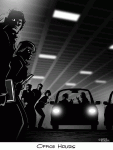

An older man meets clandestinely at night with several young people beside a building in midtown St. Louis. He hauls items from his vehicle to give them. They talk about 10 minutes and then go their separate ways.

A drug ring? A cell of conspirators? An editorial meeting?

It’s the third. The man is Avis E. Meyer, who meets each Wednesday at 8:30 p.m. with some of the section editors of the student newspaper, U. News, at St. Louis University. Professor Meyer brings them snacks and mentors them about story leads, headlines and layout. They return to a long night of work of putting the issue to bed.

Why meet outside instead of in the newspaper’s office?

“It really is odd,” said Meyer, who, for about 30 years, was the official adviser for the weekly newspaper. But for more than two years he’s been banned from stepping foot inside the office. He was replaced as adviser by the administration, but the student journalists have continued to seek advice and editing help from their favorite teacher.

The ban is the result of a longtime feud between Meyer and the president of the Roman Catholic Jesuit school, the Rev. Lawrence Biondi. Meyer says the Rev. Biondi presides over the school like an autocrat and for more than 20 years has been trying to get rid of him. Meyer said he gets blamed for just about anything published in the U. News the Rev. Biondi perceives as negative to him or SLU.

“If I didn’t have tenure, I’d be gone,” says Meyer, who adds that the Rev. Biondi wants the U. News to be more like a public relations bulletin rather than a hard news publication. Some of the stories that annoyed the Rev. Biondi over the years include: the university’s sale of its hospital, big increases in parking fees, an attempt to levy a $75 graduation fee, reporting how a Biondi homily was identical to one given a year earlier by a priest in California.

U. News pays its own way through sale of ads, and staffers pick their own editors. In 2007 the administration revised the paper’s charter to give the school more control over the editors and hired a less-experienced person to be the official adviser. Meyer has taught journalism at SLU for 35 years and worked part-time as a copy editor at the Post-Dispatch for 24 years.

Efforts by the Rev. Biondi’s subordinates to get Meyer out of the editorial page box as an adviser or mentor have been unsuccessful; editors resisted because they were upset that he was pushed out.

Diana Benanti, a former editor of the U. News, had her student stipend cut in half when administration officials came down hard on Meyer and her during a tense period in 2007. She lacked funds to continue and left SLU to attend another school for her senior year.

“I was so disgusted by what they did to Dr. Meyer. It was despicable,” she said. She’s now an editor and writer for the Riverfront Times, an alternative paper in St. Louis. She said she went into journalism “mostly because of Dr. Meyer . . . he is one of my favorite people. He’s warm-hearted and brilliant. To keep him out of the newsroom is ridiculous.”

In 2008, a SLU official ordered Meyer not to set foot in the U. News office. That’s when the editors decided to keep visiting Meyer in his office or outside the U. News office. Many of the paper’s staffers have been students in Meyer’s journalism and writing courses – classes in which students seldom earn A’s. SLU does not have an official journalism program. For 30 years, Meyer and the U. News have been it.

In a St. Louis Journalism Review story in 2007 the Rev. Biondi declined an interview, saying the questions were biased and “I have never been given a fair shake.” That was at a time the student editors thought the U. News would be moved off campus and the charter was being changed.

Meyer, to his regret, sought to incorporate the name of the paper, should it have to operate

independent of the campus. The move never occurred, but the Rev. Biondi instigated a federal lawsuit against Meyer claiming trademark infringement. And even though Meyer had voluntarily relinquished the name, the university hired an expensive downtown law firm to sue him.

While most of the suit was thrown out, it dragged on for 18 months. In a settlement, Meyer admitted registering the name of the paper without SLU’s permission. And though the case never went to trial, the Rev. Biondi sent a message to staff, faculty and students that claimed a victory over Meyer for taking “what never belonged to him in the first place.” It blamed Meyer for the lengthy court case.

U. News in an editorial called the Rev. Biondi’s statement “mean-spirited” and noted he failed to mention that Meyer had relinquished the newspaper’s name six weeks before the suit was filed. The paper ran a cartoon showing the Rev. Biondi taking money from the SLU budget and pouring it into a “frivolous lawsuit.” The editorial said, “Suing a respected professor for efforts to protect students’ free speech is no victory.”

Meyer said defending himself cost over $100,000 in legal fees he still is paying off.

“I’m broke,” he said after the settlement.

Estimates indicate the lawyers SLU hired billed for three times that amount, which presumably came out of University coffers. In a court motion, Meyer’s lawyer said “SLU has been using the court to try to punish Meyer and drain his resources.” Former students and friends held two fund-raisers for Meyer and some alumni stopped donating to SLU in protest.

Past and present editors of U. News say Meyer never tried to influence them into running negative stories about the university or its president. The Rev. Biondi, now 72, gets credit for expanding the campus, shoring up the surrounding area and increasing SLU’s endowment. The Post-Dispatch named him Citizen of the Year for 2005, citing his determination, energy and vision.

Jonathan Ernst, the current U. News editor, said he and others try not to pay attention to the Biondi-Meyer sparring but insist on keeping Meyer’s name as “mentor” on the editorial page. The official adviser looks after business matters, but is not always aware of the stories going into the paper, Ernst said.

Ernst said he gets a call exactly at midnight on Wednesdays from Meyer who checks in with final advice on headlines, “helping us boost them with strong verb choices.” The next afternoon, at Meyer’s office, Ernst gets a critique on the issue and brings back a marked-up paper to instruct other staffers.

“He’s a critical reader . . . he was copy editor at the Post, so he knows a lot,” Ernst said.

“How can you deny somebody who puts his heart into what he does? Dr. Meyer is a big asset in my learning. He’s somebody with a lot of passion for journalism. He helps us grow as journalists, students and leaders. There needs to be more Avis Meyers in the world,” Ernst said.

Meyer and his wife, Anna Marie, hold a picnic at their house for students at the end of each school year. He stays in touch with a lot of his former students, many of whom have gone on to jobs with large media companies or in public relations. He sends them, and gets back, more than 100 Christmas Cards. He recently attended a wedding of two students who met in one of his classes seven years ago and worked on U. News. They remembered he had a dog, so they named their dog “Avis.’’

Meyer, now 68, has a shelf full of teaching and advising awards. He says he’s thankful he has survived as the paper’s adviser, official or not.

“The students made, and continue to make, a difference. They kicked up a fuss,” he said.

Roy Malone, is a retired Post-Dispatch reporter, editor of the former St. Louis Journalism Review and now St. Louis editor of the Gateway Journalism Review.

The thing is, this article flat out wasn’t about the U News operating practices, simply the continuing fallout from the Avis Meyer incident. So if there are problems with when the paper gets out – that’s just part of the job. Student journalism isn’t meant to be 100% perfect all the time. REAL journalism isn’t perfect all of the time. Harsh rules don’t teach anything but unthinking discipline – something we definitely do not want out of our up and coming journalists. Ad hominem (slightly) attacks on the journalists working for the U News are a little bit pathetic. (Just like that ad hominem attack on the previous commentator)

Perhaps Avis isn’t there in the newsroom every wednesday because the university will not allow him to be there. It’s a non-argument. If he’s there every night giving out advice – without being paid to do so, I would imagine – that’s pretty remarkable. To say nothing of the midnight phone calls. I have no idea if the students are “sucking up to their professor” but a man who shows that level of dedication even when it’s not contractually necessary is a man worthy of tremendous respect. He DOES, I assume, have to go into work the next day, just like the appointed advisor. And to top it all off by pointing out that “Avis was never officially the advisor”? And he STILL does all this to help out the paper? Wow. I mean, really, wow. What a good guy.

Hello,

Thank you for your comments. I have forwarded them to our editorial team.

Can you please send me your name, contact information and one or two lines

about yourself? We like to run this with the feedback we receive.

Thanks!

Sam

I have a few comments I’d like to share. Let’s see if they get posted.

“hired a less-experienced person to be the official adviser.”

Less experience? The only way you could hire someone with as much experience as Meyer would be to hire a dinosaur.

Their current adviser works his ass of for the U News, to imply otherwise is hurtful and dishonest. Perhaps he’s not as experienced as Meyer, but truth be told the University isn’t exactly paying him anything close to what he’s worth. Not to mention his hands are tied. He’s a staff member working for the University. Anyone in that position is in a lose/lose situation. Upset your boss and your fired. Upset the student leaders and you’re ineffective.

Nothing is said to the perverse nature of Wednesday nights, where the student ‘journalists’ wait until the last possible evening to work on their stories.

Why should the U News, over any other organization that holds an office in the BSC be allowed to stay so late into the morning? The building closes at 2 a.m. The U News staff is frequently in the office until 3-5 a.m.

What lessons are being taught when the paper has no hard deadline? Wednesday night turns into Thursday morning far too often. And who is there every Wednesday, and is asked to be on time to work Thursday morning? Not Avis.

“And even though Meyer had voluntarily relinquished the name, the university hired an expensive downtown law firm to sue him.”

Do you think they would have hired an inexpensive one?

“The official adviser looks after business matters, but is not always aware of the stories going into the paper, Ernst said.”

Does the EIC let him? Or are they too busy sucking up to their professor? Seriously? The paper complains that the administration meddles too much, but when the appointed adviser isn’t checking each story that goes into the paper it’s a bad thing?

If I recall (I’m sure your superb fact-checking will prove otherwise) Avis was never officially the advisor. He took it upon himself to advise the student group. No one elected him, charged him with the duties or made it part of his faculty position.

The UNews won 4 state awards the first year after their current adviser was hired. In the second year, 17. Best in State last year, beating out Mizzou. The students launched a new website this year that they completely manage (The previous incarnation was hosted by Viacom/MTV). Not to mention the better organization of their staff to increase the number of opportunities for students to get paid and for the paper to run closer to the black in terms of advertising sales.

P.S. Nice journalism with the accompanying illustration btw, very fair and objective. Your choice makes it appear as though this is Deep Throat II, and not some melancholy professor trying to hold on to something that was ‘taken away’ due to the paper spitting out shoddy journalism.