ST. LOUIS — Five years before George Floyd died of “asphyxia-restraint” on a Minneapolis street, 27-year-old Nicholas Gilbert died in a St. Louis police holdover cell with six officers on top of him. He was handcuffed with his legs shackled while gasping, “It hurts. Stop.”

Three years before Breonna Taylor was killed by police in a flawed “no-knock” raid in Louisville, Kentucky, a St. Louis SWAT team killed Don Ray Clark, a 63-year-old Army veteran known as “Pops,” in his Dutchtown neighborhood. The SWAT team of 17 officers, acting on a no-knock warrant based on sketchy evidence, broke down the door and tossed a flashbang into the front room where Clark was sleeping. Police opened fire and Clark, who never had been charged with a crime, was shot nine times by Officer Nicholas Manasco.

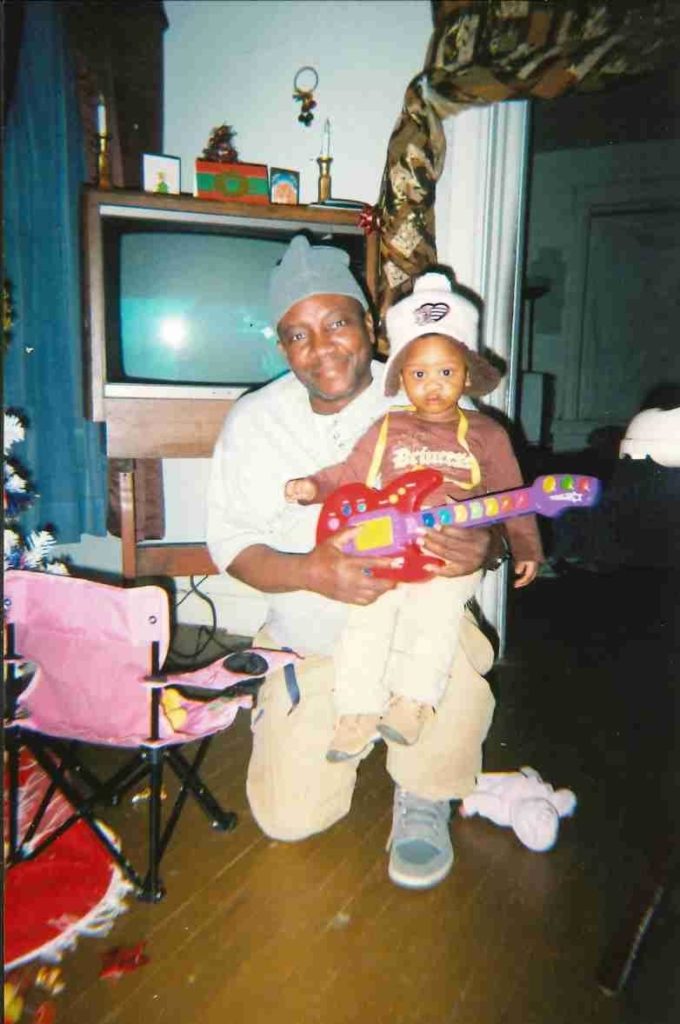

Don Ray Clark, a veteran, was killed in a non-knock drug raid at his home. He was sleeping in the front room so his daughter could have the bed. (Photo courtesy of ArchCity Defenders)

Nicholas Gilbert as a boy. At age 27 Gilbert died in a police lockup, handcuffed and legs shackled and with six police officers on top of him. (Photo courtesy of the family of Nicholas Gilbert)

Floyd’s and Taylor’s deaths were huge news events that brought worldwide attention to police killings. But Gilbert’s and Clark’s deaths only got passing attention. There were no national news stories or protests in the streets. But their deaths highlight both the banality and lack of accountability for such police actions.

Death from “asphyxia-restraint” and no-knock raids are the leading causes of police killings both in St. Louis and nationwide. Across the nation, 134 people have died from “asphyxia-restraint” in the past 10 years with 94 people killed during no-knock raids from 2010 to 2016. The Minneapolis police killing of Amir Locke on Feb. 2, 2022 during a no-knock raid targeting another man has reinvigorated the controversy about police reliance on the deadly tactic.

The families of St. Louisans Gilbert and Clark have brought attention to the killings of their loved ones by suing St. Louis and its police officers for violating their civil rights.

The lawsuit by Jody Lombardo, Gilbert’s mother, has taken on national significance because the U.S. Supreme Court took notice in a surprising June opinion that could eventually make it harder for police nationwide to dodge accountability.

Until now, there has been a disconnect between the city’s legal position on prone restraint and the public statements of its mayors. The City of St. Louis has continued to argue in court that St. Louis police did nothing wrong, even as Mayor Tishaura Jones and her predecessor Lyda Krewson criticized Floyd’s murder and advocated for police reform.

The Gilbert family’s lawyer, Kevin M. Carnie Jr., said in an interview last month that he had been astonished by the disconnect between the mayors’ statements and the city’s strident position in court. “I’ve been shocked that the city has continued to pursue the case. They say they are shocked by George Floyd but they are not upset about what happened in their own backyard.”

But that is changing. When Mayor Jones’ chief of staff, Jared Boyd, was asked about this disconnect in an interview on Sept. 7, he said the mayor was taking steps to reconsider the city’s legal position. The mayor appointed a new city counselor to review the city’s legal position in police abuse cases, with less consideration for the financial loss such cases might mean for the city. The new city counselor is Sheena Hamilton, the first Black woman to hold the job.

Already the city has gone to court to challenge the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights passed on the last day of the legislative session in May. That law creates a new legal roadblock to police accountability by giving officers extra legal protections that citizens don’t enjoy.

The change in the City Counselor’s office is part of a larger reform in which the mayor is proposing an Office of Public Accountability to put civilians with subpoena power in charge of police misconduct investigations, Boyd said.

Carnie, the lawyer, said he was glad to hear the city is reconsidering its legal position. “My client is happy to hear that the city is taking a fresh, closer look at this case. Hopefully the city will implement a much needed change in policy and training as a result.”

Two common legal roadblocks

The Gilbert case highlights two of the steepest roadblocks to police accountability: objective reasonableness and qualified immunity. Objective reasonableness bars judges and juries from second-guessing the officer on the scene. Qualified immunity protects an officer from being held accountable for illegal practices if the courts have not clearly determined them to be illegal.

The two doctrines together give officers across the country the benefit of the doubt in cases of alleged police abuse and killings.

The City of St. Louis has argued in court that both doctrines should protect the officers involved in Gilbert’s killing.

In characteristically proactive language in the city’s legal brief last year, Deputy City Counselor Robert H. Dierker calls Gilbert’s mother’s arguments to the Supreme Court “agitprop” designed to “use published reports regarding the death of George Floyd as a cudgel to try to browbeat this Court into reviewing a case that is a straightforward application of basic Fourth Amendment principles. The only things in common between this case and the reports regarding George Floyd are drug use and heart disease.”

But Carnie, the Gilbert family’s lawyer, said the nation’s horrified response to the death of Floyd under a police officer’s boot shows that police can’t be given the discretion to “put a handcuffed person face-down on the ground and push into him until he suffocates.”

Just before Christmas 2015, police found Gilbert in an abandoned home and discovered that he had failed to appear in court on a traffic violation. They arrested him. In the police holdover cell, Gilbert seemed to be putting something around his neck. Fearing a suicide attempt, officers piled into the 7-by-9-foot cell and were met with a struggle from the 5 feet 3 inch, 160 pound 27-year-old. They handcuffed him, manacled his legs and then pushed him into the floor.

Gilbert tried to lift himself up and yelled pleas for help, according to court records.

“It hurts. Stop.” Those were his last statements. After 15 minutes, during which six officers weighing a combined total of 1300 pounds were on top of him, he stopped breathing. The officers couldn’t find a pulse.

An autopsy found a fractured sternum and contusions and abrasions on his shoulders and upper body. A medical report stated that the “cause of death was forcible restraint inducing asphyxia,” while methamphetamine and heart disease were “underlying factors.”

A district court judge agreed that Gilbert had died from asphyxiation, but threw out the lawsuit based on qualified immunity: that no court had clearly ruled that it was illegal for police officers to put hundreds of pounds of pressure on a prone suspect who was shackled and resisting. Because the officers couldn’t be held accountable, neither could the city, the judge ruled.

The 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis took it a step further. It said it didn’t even have to get to the qualified immunity issue. Applying the “objective reasonableness” standard, it found that no reasonable jury could decide that the officers used unreasonable force.

The U.S. Supreme Court, at the end of its session in June, disagreed with the 8th Circuit and told it to take another look. It cited a “well-known police guidance recommending that officers get a subject off his stomach as soon as he is handcuffed” because of the risk of suffocation.

“Struggles of a prone suspect may be due to oxygen deficiency, rather than a desire to disobey officers’ commands. Such evidence, when considered alongside the duration of the restraint and the fact that Gilbert was handcuffed and leg shackled at the time, may be pertinent” to how much of a threat could be “reasonably perceived by the officers.”

“Having either failed to analyze such evidence or characterized it as insignificant, the court’s opinion could be read to treat Gilbert’s ‘ongoing resistance’ as controlling as a matter of law. Such a per se rule would contravene the careful, context-specific analysis required by this Court’s excessive force precedent,” the court said.

In other words, the Supreme Court is saying that courts can’t say police are always acting reasonably when they apply pressure to a prone suspect who appears to be resisting. It was remarkable the court took the action without even hearing oral arguments.

Justices Joseph A. Alito Jr., Clarence Thomas and Neil M. Gorsuch — the three most conservative justices — disagreed with the Supreme Court’s action. Alito wrote that the court should give the appeals court the benefit of the doubt in its opinion — which would amount to giving the benefit of the doubt to a court interpretation that was already giving the benefit of the doubt to police. The benefit of the doubt on top of the benefit of the doubt.

Significantly, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. didn’t agree with Alito even though he did the last time the court resolved a similar case — the 2015 Kingsley decision involving a pretrial detainee in Wisconsin who had been handcuffed, tased and allegedly knocked into a concrete bunker. In Kingsley, Roberts had joined the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent, which stated, “The Constitution contains no freestanding prohibition of excessive force.” Even the infliction of “objectively unreasonable harm” by officers does not violate the Constitution, he said, accusing the majority of being “tender hearted.”

Not only did Roberts desert the conservatives in the Gilbert decision, but two new conservative justices — Brett M. Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett — joined him in agreeing with the three liberal justices that cases of prone restraint needed more court scrutiny. Roberts is a savvy chief justice and most likely didn’t want to be opening the door to police abuse in prone restraint cases just as a jury in Minnesota was determining Floyd’s death to be murder.

Lombardo, Gilbert’s mother, says the only difference between her son’s death and Floyd’s was that St. Louis police “weren’t videoed.” Former St. Louis Police Chief Sam Dotson backed his officers but did take steps to introduce video in the holdover cells.

Lombardo said in an interview that she is angry that the police “smeared” her son’s name. “Why when the police kill do they have to attack his character?”

Lombardo acknowledges her son had drug problems but says he wasn’t homeless, as police claimed. “Nick was a happy, young man and full of life. He was funny and a jokester. His little sister, 10 years younger, struggles every day about losing her brother. He was learning flooring from his dad and his uncles. They say he was homeless, but they knew my address.

“If Nick’s case had gotten notoriety … it could have saved (Floyd) and could have saved a lot of other people. … I can’t even watch the George Floyd video. I think of my own son.”

Even if the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agrees that police acted unreasonably, the court would then have to consider qualified immunity. Because the 8th Circuit Court itself thought the officers’ actions were reasonable before, it’s hard to see how it could conclude they should have known they were illegal.

But Carnie points out that the Justice Department issued guidance in 1995 to all law enforcement officers to avoid pressing on prone suspects who were restrained for fear of suffocation. He argues that because this guidance is 26 years old, officers in St. Louis should have known it.

In a court filing this August, Carnie pointed to multiple federal appeals courts that have ruled that the law against putting force on a bound, prone prisoner has been “clearly established” and therefore should not allow officers to escape through the qualified immunity loophole.

Dierker’s response for the city was that the Supreme Court had actually “found no fault” with the 8th Circuit’s decision — even though it had sent it back to the appeals court with an opinion expressing disagreement. Dierker said the appeals court shouldn’t spend any more time on arguments before it “put(s) an end to this case.”

A flash-bang and then 9 bullets

No-knock drug raids date back to the Nixon administration’s war on crime in the 1960s. Local officials also began to use the tool of obtaining a no-knock warrant from a judge that enabled officers to break down the door without knocking. The tactic was supposed to be used in “exigent” circumstances where suspects were armed or might flush drugs before officers could seize them. One purpose was to safeguard officers from armed suspects.

A nationally notorious no-knock raid occurred in 1973 in Collinsville, across the river from St. Louis. Twelve law enforcement officers were indicted for a series of raids on 12 different homes, conducted without enough evidence of wrong-doing on the part of the accused.

Clark’s family and lawyers say the fatal Feb. 21, 2017, no-knock raid on Clark’s home was based on false information.

The no-knock warrant obtained by Officer Thomas Strode was the 27th no-knock warrant of the year, all approved by a judge. Many of Strode’s applications used the same boilerplate language claiming unidentified — and unverified — confidential sources said guns and weapons were in the home so it was too dangerous to knock on the door and execute a search warrant.

The warrant in Clark’s case portrayed the 63-year-old veteran in a way his children, Donald Ray Clark Jr. and Sherrie Clark-Torrence, didn’t recognize.

In a video about their father, they spoke of an Army veteran who was a disciplinarian who worked in security before multiple health problems diminished his eyesight and hearing and he required a cane. Clark had recently moved into his daughter’s house so that a younger daughter, 8, could have her own bedroom. Clark went to bed around 8 p.m. every evening on a couch in the front room. Worried about crime, he put extra screws into the front door to strengthen it. Clark had never been charged with a crime.

In contrast, the no-knock warrant portrayed Clark as being central to a three-home drug ring on California Avenue: Clark’s house at 4023 and his neighbors’ at 4025 and 4029.

After searching 4025 and 4029, more than 17 heavily armed officers of the SWAT team lined up to enter Clark’s home, where he was asleep after a difficult day riding the bus to doctor appointments.

The officers broke down the door and Officer Ronald Mueller threw a “diversionary device” into the front room where Clark slept. It went off with a loud flash and bang, disorienting Clark. Police did not identify themselves as they piled in, according to the lawsuit.

Moments later, Officer Nicholas Manasco opened fire with an assault rifle, hitting Clark with a hail of nine bullets. Manasco said he was responding to gunfire, but the lawsuit says Clark was unarmed. Clark fell to the floor and mumbled a few words. Manasco and Officer James Zwilling stood over Clark, pointing their weapons at him while other officers rushed by and searched the house, the lawsuit alleges. None of the officers immediately called for medical assistance. When Clark Jr. got to his father’s house, police wouldn’t tell him what had happened or where his father had been taken. He and his family didn’t receive word of their father’s death until the following day.

Manasco said Clark had fired at him and police said they had found drugs. The lawsuit claims Clark didn’t have a gun and the drugs were brought into the house from a nearby house. Chief Dotson cleared his officers of wrongdoing.

Officer Manasco has killed two other civilians — including Isaiah Hammett a few months later in another SWAT raid for which he and the city were sued. Police entered Hammett’s residence with a flashbang and fired 93 shots, hitting Hammett 24 times. In 2011 Manasco killed Carlos Boles, took pictures of his bullet-ridden body and showed them to another officer. An investigation was announced, but the Boles episode did not remove Manasco from the SWAT team. Manasco retired from the department earlier this summer.

Last fall, Missouri legislators heard testimony from across the state about the abuses of no-knock warrants. But the Missouri Sheriffs’ Association and Missouri State Troopers’ Association, which have powerful voices in the Legislature, claimed they are used so rarely that there is no need for regulation.

Five other states voted to restrict no-knock warrants in response to Breonna Taylor’s death in Louisville, Kentucky.

Editor’s Note: This story first published on Dec. 21, 2021 in the print magazine.

William H. Freivogel is publisher of GJR, a professor of media law at Southern Illinois University Carbondale and a member of the Missouri Bar.