The most important words in the 14th Amendment of 1868 – maybe in the entire Constitution – say no state shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law, nor deny any person…the equal protection of the laws.”

These promises of liberty, due process and equality eventually remade the country, remade the Constitution and by the 1960s, protected the privacy, individual dignity and personal autonomy of every person.

The 14th Amendment was written in the blood of the 750,000 Americans who died in the Civil War. And it took 150 years of political movements to breathe life into the words – the civil rights movement, the women’s rights movement and the gender equality movement.

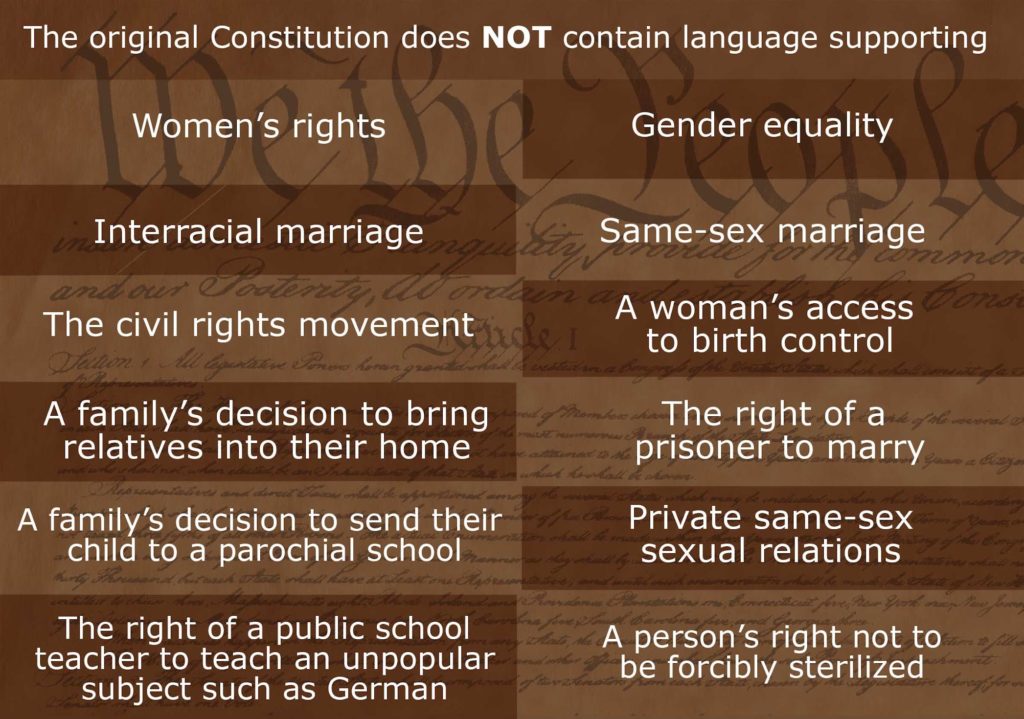

Those few words protect interracial marriage, same-sex marriage, private same-sex sexual relations, a woman’s access to birth control, the right of a prisoner to marry, a family’s decision to bring relatives into their home, a family’s decision to send a child to a parochial school, the right of a public school teacher to teach an unpopular subject such as German and a person’s right not to be forcibly sterilized.

In addition, the Supreme Court has interpreted the liberty protected by due process to incorporate nearly all of the freedoms of the Bill of Rights – the other great wellspring of freedom in the Constitution. Before the 14th amendment, the Bill of Rights only applied to the federal government, not the states. So, states could willy-nilly violate rights named in the Bill of Rights. And they did.

In short, much of the freedom Americans take for granted rests on liberty protected by due process. The abortion right rested on these words, too, until the Supreme Court changed its mind earlier this year.

It took a century of Supreme Court decisions to bring these words alive from decisions about the family, to decisions about women’s rights, to decisions about contraception and reproductive freedom to decisions about marriage.

There is a legal term for the liberty protected by due process. Most people haven’t heard it and it is somewhat confusing. It’s called “substantive due process.” What that means is that due process doesn’t just assure that government procedures will be fair. It also protects the substance of the right – liberty in this case.

Understanding this history is key to understanding the significance of the Dobbs v. Jackson decision overturning Roe v. Wade. Roe was anchored in the liberty protected by due process. One of the reasons that the Dobbs opinion alarmed some legal experts is that it called into question the legal rationale for this century of decisions expanding privacy and personal freedom.

Historically, conservative originalists on the court, such as Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and the late Antonin Scalia, don’t like substantive due process. More liberal justices think it is essential to protecting privacy.

In Dobbs, Alito wrote that, “Substantive due process” can be “treacherous” and lead the court to “usurp” elected officials.

Alito argued that liberty protected by due process should be limited to those freedoms ‘deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition” and ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.”

That language comes from a 1937 decision, Palko v. Connecticut, where the court explained why double jeopardy was not fundamental enough to be included in rights the states had to recognize. The court subsequently also said the right to a lawyer and trial by jury were not fundamental enough either, although the Warren Court reversed all of those decisions in the 1950s and 1960s.

The truth is that many of the liberty rights protected by the court in the past hundred years are not deeply rooted in the nation’s history. There were no legally protected same-sex marriages before the 21st century. Half the states made interracial marriages and contraception illegal as late as the 1960s. The Comstock Act after the Civil War made contraception illegal because it tempted women to be overly lustful.

In Dobbs, Alito hastened to add that the court was only addressing abortion – not these other substantive due process rights, noting that abortion was different because of the potential for human life.

But Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in a separate concurrence that the court should look at same-sex marriage and contraception as well. That is one of the reasons that the Congress moved quickly this fall to protect same-sex and interracial marriage.

In addressing what he considers the abuse of substantive due process, Alito said the nation must “guard against the natural human tendency to confuse what that Amendment protects with our own ardent views about the liberty that Americans enjoy.”

He noted that two of the most infamous Supreme Court decisions in history – Dred Scott v. Sanford in 1857 and Lochner v. New York in 1905 – were substantive due process decisions – and they were disastrous. In Dred Scott, the court said that a slaveholder’s due process right to property was violated by laws against slavery in the territories. And in Lochner, during the Gilded Age around the turn of the 20th century, the court said a state law limiting bakers’ hours violated the liberty of contract protected by due process.

Alito went on to ridicule as too broad the reasoning of the 1992 Casey decision in which two justices appointed by Ronald Reagan and one by George H. W. Bush – Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony M. Kennedy and David H. Souter – joined liberals in reaffirming the abortion right. Those justices said the abortion right was based on freedom to make “intimate personal choices” “central to personal identity and autonomy. At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and the mystery of human life.”

The justices in Casey also injected an equality element to their court ruling. A number of the court’s decisions on personal privacy have linked liberty interests and equal protection – the two ends of that important sentence in the 14th amendment. Both liberty and equality are the basis of the Loving v. Virginia decision in 1967 throwing out laws against interracial marriage and the Obergefell v Hodges decision of 2015 recognizing the right to same-sex marriage.

Alito directly dismissed the equality argument from Casey saying it was overtaken by “modern development” that have helped women – laws against pregnancy discrimination, family leave laws, new attitudes toward unmarried mothers, better health care and more provisions for placing infants left at hospitals up for adoption. Feminists were furious that Alito had used progressive women’s rights legislation as a justification for denying the right to an abortion.

Brandeis’ ‘right to be let alone’

The word privacy does not appear in the Constitution, although there are elements of the Bill of Rights that suggest the Framers were concerned about privacy. The First Amendment protects the right of association. The Third Amendment says people can’t be forced to quarter troops in their homes. The Fourth Amendment says, “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated.” The Fifth Amendment says suspects have the right to remain silent. And the Ninth Amendment protects the rights not enumerated in the others.

Still, the word privacy isn’t used.

The person who first wrote about a legal privacy right was Louis Brandeis, who published the most famous law review article in history, “The Right to Privacy,” along with his law partner Samuel Warren. (Brandeis, by the way, began his legal career in St. Louis where he was admitted to the bar in 1878 in the Old Courthouse where the Dred Scott case had been argued.)

Brandeis and Warren were upset by what they thought was the crass way the press, toting portable cameras, covered upper class social events.

Warren, a Boston blue blood, had married Mabel Bayard, the daughter of a senator and friend of President Grover Cleveland’s young wife, Frances Folsom. The press covered the wedding in 1883 in great detail. The Washington Post story was headlined: “A Ceremony in the English Style Attended By the Blue Blood of Delaware and Boston.” It commented that the wedding was one “for which there had been hopes and fears, heart flutterings, and silent longings.”

In the years that followed, the press covered the Warren-Bayard social gatherings in Boston and the visits between Mabel Bayard and the young First Lady. Grover Cleveland’s female friends had been the source of a great deal of comment in the press. Cleveland acknowledged fathering a child out of wedlock with another woman and his courtship of the young Frances Folsom, 28 years his junior, was much covered. The New York Times had reported on the relationship between Cleveland and Folsom in an 1886 article headlined, “The President’s Sweetheart.”

In a speech at Harvard in 1886, Cleveland criticized the press as “purveyors of ‘silly, mean, and cowardly lies that every day are found in the columns of certain newspapers which violate every instinct of American manliness, and in ghoulish glee desecrate every sacred relation of private life.’”

These press reports, along with the new technology of the movable camera, inspired Brandeis to develop the new legal theory of privacy.

Brandeis and Warren began their article by observing that the common law had recognized protections for liberty and property through history. But they said times had changed. They found a right to privacy in the “right to life.” “The right to life,” they wrote, “has come to mean the right to enjoy life, – the right to be let alone”

Brandeis and Warren left no doubt that they were responding to newspapers and that era’s advance in technology – the movable camera that allowed photographers to take photos of people without permission. They wrote:

“Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; and numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.’”

Brandeis and Warren noted that E.L. Godkin, founder of the Nation, had criticized sentimentalism in the press. He had written about a case brought by a dancer, Marian Manola, against a photographer who had secretly photographed her from a theater box as she was playing a role requiring her appearance in tights.

“The press is overstepping in every direction the obvious bounds of propriety and of decency,” wrote Brandeis. “Gossip is no longer the resource of the idle and of the vicious, but has become a trade, which is pursued with industry as well as effrontery. To satisfy a prurient taste the details of sexual relations are spread broadcast in the columns of the daily papers. To occupy the indolent, column upon column is filled with idle gossip, which can only be procured by intrusion upon the domestic circle.”

They wrote that gossip, “both belittles and perverts. It belittles by inverting the relative importance of things, thus dwarfing the thoughts and aspirations of a people. When personal gossip attains the dignity of print, and crowds the space available for matters of real interest to the community, what wonder that the ignorant and thoughtless mistake its relative importance.”

First cases

By the time that Brandeis was on the Supreme Court, the new technology that was raising privacy questions was wiretapping. In Olmstead v. United States in 1928, the court concluded that wiretapping did not violate the Fourth Amendment because it did not involve trespass into a person’s home. “There was no search of the defendant’s houses or offices,” the court wrote.

Brandeis dissented. He did not mention his law review article but his words resonated with the same views, including his phrase about the right to be let alone. “Subtler and more far reaching means of invading privacy have become available to the government.” he wrote. “Discovery and invention have made it possible for the government, by means far more effective than stretching upon the rack, to obtain disclosure in court of what is whispered in the closet.”

Brandeis said that the Framers “knew that only part of the pain, pleasure and satisfaction of life are to be found in material things. They sought to protect Americans in their beliefs, their thoughts, their emotions and their sensations. They conferred, as against the government, the right to be let alone – the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men.”

Development of constitutional right to privacy

During Brandeis’ first decade on the Supreme Court, the right to privacy came up in contexts that did not involve the media but rather in the rights of individuals to control their bodies, families and other private decisions.

The cases involved the right of a school teacher to teach German, the right of Catholic parents to send their children to parochial schools and the right of a woman with a low I.Q. to have a baby. These decisions involving the autonomy of the individual and the family became the constitutional basis of the right to privacy.

Robert T. Meyer was arrested on May 25, 1920 for teaching German to 10-year-old Raymond Parpart. He was sentenced to 30 days in jail and a $25 fine.

Nebraska and 21 other states had passed laws against foreign language instruction in reaction to immigration, in bitterness toward Germans after World War I and in reaction to the Russian Revolution. The Nebraska law said only English could be taught to children before eighth grade so that English would become their “mother tongue.” The state claimed it had the power to “compel every resident of Nebraska so as to educate his children that the sunshine of American ideals will permeate the life of the future citizens of this Republic.”

The Supreme Court threw out the law. It said that the “liberty” protected by the 14th Amendment was more than freedom from bodily restraints. It also included “the right of the individual to contract, to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.”

The same angry political atmosphere in the United States led to Oregon passing a law in 1922 requiring that all children between 8 and 16 attend public schools. Gov. Walter M. Pierce said that if “the character of the education of such children is to be entirely dictated by the parents of such children,…it is hard to assign any limits to the injurious effect from the standpoint of American patriotism.”

The Catholic Society of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary challenged the law arguing they could teach patriotism just as well as the public schools.

The Supreme Court again struck it down writing, “The fundamental theory of liberty upon which all governments in this Union repose excludes any general power of the State to standardize its children by forcing them to accept instruction from public teachers only.” The child is not the “mere creature of the state,” the court said.

The court was not so protective of privacy rights, however, in the shameful case involving the sterilization of Carrie Buck. Buck was a young woman in Virginia who was sterilized because she did poorly on an I.Q. test. Half of the white males were categorized as morons under the test.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, famous for his decisions championing free speech, wrote the decision upholding the sterilization. He noted that Buck, her mother and daughter all were mentally defective and declared, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” Holmes left out mention that one of Buck’s daughters made the honor roll.

Holmes later wrote a friend that it “gave me great pleasure” to uphold the sterilization law because of his worries about overpopulation and fears that whites would be overwhelmed by brown and yellow races.”

By 1942, the Supreme Court was ready to turn away from its Buck decision. Oklahoma law permitted the sterilization of habitual criminals and a judge had ordered a vasectomy for Jack T. Skinner, whose three felonies included stealing chickens. Justice William O. Douglas wrote, “We are dealing here with legislation which involves one of the basic civil rights of man. Marriage and procreation are fundamental to the very existence and survival of the race.”

Griswold v. Connecticut

One of the most famous privacy cases in Supreme Court history was Griswold v. Connecticut in which the court ruled that laws against providing birth control to married women were unconstitutional.

The decision was handed down in 1965, but the controversy had begun in the 1920s. Katherine H. Hepburn, the mother of the famous actress, was one of three organizers of a public meeting in 1923 that led to the formation of the Connecticut Planned Parenthood League to fight the law. First attempts failed.

Subsequently, Dr. C. Lee Buxton, head of the Yale Medical School’s obstetrics unit in the 1950s was shocked to discover that he could not prescribe birth control devices for his married patients. He joined forces with Estelle Griswold and Yale law professor Fowler V. Harper to bring a lawsuit.

Griswold, a Junior Leaguer, opened an eight-room birth control clinic in New Haven in 1961. She knew she was likely to be arrested. That was the point. She wanted to challenge the state law. Griswold was arrested and charged. The criminal complaint said her crime was that she “did assist, abet, counsel, cause and command certain married women to use a drug, medicinal article and instruments, for the purpose of preventing conception.” Both Griswold and Dr. Buxton were convicted and fined $100 each. On June 7, 1965 the Supreme Court voted 6-2 to overturn the convictions.

The court’s decision recognized a constitutional right to privacy for the first time, but no five justices had the same rationale for where in the Constitution they found that unenumerated right.

Justice Douglas, who wrote the main opinion, reasoned that “specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.”

He said that five amendments in the Bill of Rights created these “zones of privacy.” They were the First Amendment’s freedom of association, the Third Amendment’s limits on quartering troops, the Fourth Amendment’s freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures, the Fifth Amendment’s right against self-incrimination and the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people.

“The present case then,” wrote Douglas, “concerns a relationship lying within the zone of privacy created by several fundamental constitutional guarantees…We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights – older than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage is coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to a degree of being sacred. The association promotes a way of life, not causes; a harmony in living, not political faiths; a bilateral loyalty, not commercial or social projects. Yet it is an association for as noble purpose as any involved in our prior decisions.”

Three other justices said they agreed with Douglas but issued their own opinions. Justice Arthur Goldberg expanded on the role of the little used Ninth Amendment. He quoted from James Madison’s speech to Congress stating the importance of the Ninth Amendment in protecting rights not enumerated in the Bill of Rights. “To hold that a right so basic and fundamental and so deep-rooted in our society as the as the right of privacy in marriage may be infringed because that right is not guaranteed in so many words by the first eight amendments to the Constitution is to ignore the Ninth Amendment and to give it not effect whatsoever.”

Two other members of the majority – Justices Byron R White and John Marshall Harlan – said they could not agree with either Douglas or Goldberg. They said that the law violated a liberty protected by the 14th Amendment.

In retrospect, Douglas’ opinion about constitutional penumbra – the light, outer part of a shadow – may have done more harm than good. It was often ridiculed and turned out not to be a convincing constitutional home for protecting privacy.

Loving v. Virginia

A little after midnight in July, 1958, Caroline County Sheriff Garnett Brooks and his deputy invaded the bedroom of Mildred and Richard Loving, demanded they get out of bed and hauled them off to jail.

“They were standing over the bed,” Mildred Loving recalled in an interview we had in 1987 in her rural Virginia farmhouse. “They told us to get up and get dressed, that we had to come with them.

“I was crying. I was scared and confused – and angry that they would walk into our home without so much as a knock. The sheriff asked Richard why did he marry me. Richard got kind of smart and asked him why did he marry his wife.”

Brooks put the Lovings in the police car and carted them off to jail, drinking whiskey along the way.

The criminal charge was simple: “Richard Perry Loving being a white man and said Mildred Delores Jeter being a colored person did unlawfully go out of the State of Virginia for the purpose of being married” and were “cohabiting as a man and wife against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth.”

Virginia was one of 17 states at the time that criminalized inter-racial marriage. Missouri was another.

“I am sure now the sheriff was joking when he asked a black trusty if he wanted to spend the night with me. It scared me so, I hate to think about it,” she recalled.

The Lovings were found guilty in January, 1959. Judge Leon M. Bazile said, “Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.”

Bazile levied a one year sentence but said he would suspend it if they got out of the state and stayed out for 25 years.

The Virginia courts later upheld the state law saying that its purpose was to “preserve the racial integrity of its citizens” and prevent “the corruption of blood,” “a mongrel breed of citizens” and “the obliteration of racial pride.”

After the Lovings were convicted, they moved to Washington for a time and Richard worked as a bricklayer, but they missed their families and hometown and moved back.

Mildred lay awake at night because she was afraid the police would come.

“I had all parts of thoughts at night,” she said. “Is this the night the police will come? What can we do if they come? Maybe if I keep a light on they would think we are not asleep and go away. How did we get into this mess? Is it worth the hassle? Why didn’t we stay in D.C.? God help us please.”

Virginia defended its law saying marriage was traditionally a state matter. The court should stick to the original intent of the authors of the 14th Amendment, the post-Civil War amendment. The authors had no notion that equal protection of the law or protecting people’s liberties would include interracial marriages.

Congressmen had said during the debate that the amendment would not affect laws against interracial marriages.

The Supreme Court threw out the Virginia law on June 12, 1967. The law violated both the equality and liberty promises of the 14th Amendment, the court said.

“The freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men,” wrote outgoing Chief Justice Earl Warren. “To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications…so directly subversive to the principle of equality at the heart of the 14th Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty without due process of law.”

Roe v. Wade six years later and Obergefell v. Hodges, 48 years later, cited this same reasoning – this marriage of liberty protected by due process with equal protection – in support of the personal decisions to have an abortion and to marry a person of the same gender.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Loving was perfectly timed to the changing social mores. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, about the marriage of an interracial couple, came out six months after Loving and was a box office hit, even in the South. The Black protagonist, Sidney Poitier, was a Nobel prize winning doctor.

Roe v. Wade

In 1972, the court expanded Griswold by ruling that states could not ban the distribution of birth control devices to unmarried persons. Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote, “If the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child.”

The Griswold decision set the stage for the most important privacy decision of the 20th Century – Roe v. Wade.

Sarah Weddington, a young lawyer in Austin, Tex. in the late 1960s, often heard that pregnant women were traveling to Mexico from that university town to have abortions. Many women came back with infections

Norma McCorvey, of Dallas, brought Weddington the test case she was looking for. McCorvey was unmarried and pregnant with her second child. Her first child was being reared by her mother. McCorvey, a high school dropout, couldn’t hold a job and feared she’d lose her job waitressing if her pregnancy became known.

Justice Harry Blackmun wrote the opinion for the court striking down the Texas law. Blackmun was a Nixon appointee and expected to vote along with Chief Justice Warren Burger. They were called the Minnesota twins. But Blackmun surprised everyone.

Father of three assertive daughters and husband of a forceful wife, Blackmun spent the summer of 1972 in the Mayo Clinic researching abortion. The research led him to the trimester formula. During the first trimester of pregnancy, the abortion decision should be the woman’s in consultation with her doctor. During the second trimester, the state could regulate abortions consistent with the health of the mother. After the fetus was viable – could live outside the womb – the state could prohibit abortion unless the life or health of the mother was at stake.

Blackmun concluded that a woman’s “right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision, but…this right is not unqualified and must be considered against important state interests in regulation.”

The 7-2 decision lacked a clear statement about where the court found the unenumerated right to privacy. Blackmun used equivocal language: “The right of privacy, whether it be founded in the 14th Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or…in the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.”

In Dobbs, Alito maintained this equivocal language left the right in doubt.

Firing pregnant teachers

The court again relied on both liberty and equal protection in protecting teachers from pregnancy discrimination.

In 1970, Jo Carol LaFleur, then 23, became pregnant while a teacher at Patrick Henry Junior High School in Cleveland. School board policy required pregnant teachers to take unpaid leave five months before birth. They could reapply for a position the school year after the baby turned three months but would be subject to a physical exam and wouldn’t get a job unless one was open. The schools said pregnant women often couldn’t perform required duties during the last five months of pregnancy and that the policy was intended to protect the health of the mother and baby.

LaFleur was forced to resign in March when her due date wasn’t until July. The Supreme Court ruled in 1974 that the policy violated LaFleur’s liberty protected by the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment.

“Freedom of personal choice matters of marriage and family life is one of the liberties protected by the due process clause,” the court decided.

Taking in a grandson

When John J. Moore Jr.’s mother died before his first birthday, he went to live with his grandmother, Inez Moore, who owned a 2/1/2 story frame duplex in East Cleveland.

Inez Moore had raised six of her own children. She became John Jr.’s legal guardian and the boy fit in easily with the large extended family in the duplex.

Trouble began six years later when the City of East Cleveland decided that there were two families living in the house because another grandson of Inez’s, Dale, also was living in the duplex. The two boys were cousins and Dale was like a younger brother to John.

But to East Cleveland, which was trying to stem the migration of Blacks from Cleveland proper, two families in one house was a violation of the housing code. It fined her $25 and sentenced her to five days in jail.

In 1977, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that Inez Moore had every right to bring her extended family under one roof.

Justice Lewis Powell, a Nixon appointee, relied on substantive due process, writing that the court “has long recognized that freedom of personal choice in matters of marriage and family life is one of the liberties protected by the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment…”

When Moore died in 1983, she had a special provision in her will requesting that her home be maintained as a place of refuge for her children and grandchildren.

Gay sex is illegal in 1986, but not in 2004

An Atlanta police officer, Patrolman Keith Torrick, was serving a warrant at Michael Hardwick’s home in 1983. After stepping into the apartment, he looked through an open bedroom door and saw Hardwick in a bathroom having oral sex with a man – then, a crime in Georgia.

The Supreme Court upheld the law 5-4 in a controversial 1986 decision, Bowers v. Hardwick. Justice Byron R. White wrote the decision announcing that none of the court’s previous privacy cases “bears any resemblance to the claimed constitutional right of homosexuals to engage in acts of sodomy…No connection between family, marriage or procreation on the one hand and homosexual activity on the other has been demonstrated.”

Justice Powell later acknowledged that he had switched sides after having initially voted to strike down sodomy laws.

Blackmun, the author of Roe, had to change his draft majority opinion into a dissent. He quoted from Brandeis about the “right to be let alone” being the most comprehensive right of man.

It appeared at the time that the Supreme Court would soon be heading farther to the right with the nomination of Robert Bork to replace Powell moving toward the Senate. But Bork was defeated because he told the Senate straight out that there was no right of privacy. Anthony M. Kennedy was elevated to the court instead.

In a twist that no one predicted at the time, Kennedy became the most important advocate of same-sex rights on the court, writing a string of 5-4 decisions extending constitutional protect to same-sex sodomy and same-marriage.

Lawrence v. Texas in 2004 overturned Bowers v. Hardwick only 18 years after it had been decided. Then, the court threw out the Defense of Marriage Act and in 2015 recognized a constitutional right to same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges.

Kennedy breathed new life into the 14th Amendment’s protection of what he called “equal liberty.” Kennedy relied on the Loving interracial marriage decision and the LaFleur pregant teacher firing to merge liberty and equality.

Kennedy didn’t use the word privacy. He talked about liberty, a word that is in the Constitution. He wrote in the 2015 same-sex marriage decision that “the right to personal choice regarding marriage is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy…Like choices concerning contraception, family relationships, procreation, and childrearing, all of which are protected by the Constitution, decisions concerning marriage are among the most intimate that an individual can make.”

Justice Alito made clear in Dobbs that he doesn’t think much of Kennedy’s high-flown language. But he also made clear that he was limiting Dobbs to abortion where another potential life is involved.

Except for Justice Thomas, the conservative majority on the Supreme Court doesn’t seem to have any plans to apply its reasoning to same-sex marriage or relations or interracial marriage. Congress and the president decided this month not to take any chances and passed a law requiring same-sex and interracial marriages be recognized across the country.

Click here to support Gateway Journalism Review with a tax-deductible donation. (GJR was founded as the St. Louis Journalism Review.)

William H. Freivogel is a professor and former director of the School of Journalism at SIUC. He is the publisher of Gateway Journalism Review.