In the fall of 1976, as a young reporter at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, I was in the early stages of researching a project on nuclear waste. A source told me of key leads contained in an article that had appeared several years earlier in The Rocky Mountain News. To get a copy of the article entailed, first, asking an editor for permission to make a long-distance call; and second, persuading the News reference department to dig the story out of its morgue, make a photocopy of it, and send that copy to me by mail. A week or so later I had the information I sought.

Getting that bit of research was slow, to the world of today, but there was also the expectation, in 1976, that the information I got had been carefully reported and edited, with a premium on accuracy. I also knew that I had the luxury of time, in what became four months of travel, visiting every significant nuclear waste site in the United States and in the United Kingdom and interviewing nearly a hundred experts in the field including two Nobel laureates who had been part of the Manhattan Project.

We’ve come a long way since.

Holding a universe of knowledge—and rank disinformation—in the palm of our hands. The ability to call anyone, anywhere, for free. The collapse of journalism gatekeepers, the politicization of higher education and K12, the proliferation of silos fueled by algorithms to parrot our own worst prejudices. The degeneration of big-tent political parties into polarized factions dominated by the extremes.

As terrible as all that is — and much of it is terrible indeed — these past few decades have also seen the democratization of journalism (anyone can be a publisher), new strategies for raising the voices of marginalized communities, a once taboo willingness to collaborate across platforms and outlets, and the remarkable emergence of innovative ways of engaging broad communities in the issues that affect us all.

I want to highlight a few signposts along the way, and lessons learned, from moments in my own career that encapsulate these trends, beginning with three decades at the Post-Dispatch and then nearly 20 years at the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, the non-profit journalism and education center I founded in 2005.

Post-Dispatch core values

I’ll start with ambition and independence, two core values at the Post-Dispatch when I came to St. Louis as a 22-year-old in 1974 that are just as essential to quality journalism today as then.

We were taught to think big, aim high, swing for the fences—and to be fiercely independent.

The nuclear project was a case in point—a seven-part series exposing the unsolved challenge of safe permanent disposal of nuclear waste at a time when Missouri’s biggest utility was embarked on building the state’s first nuclear power plant.

In the early 1980s I spent nearly two years investigating defense contract fraud at McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics, at that time the two biggest defense contractors in the country and both of them headquartered in St. Louis. Together with Bill Freivogel and other colleagues we produced some 400 stories, including one especially memorable report on the leak of incriminating documents and tape recordings from a top General Dynamics executive in Greece, on the run from an indictment, that I dictated to Bill in Washington with a Post-Dispatch lawyer in St. Louis vetting the language as we wrote.

In 1986, as the Duvalier dictatorship was crumbling in Haiti, all commercial flights into Port au Prince were canceled and photographer J.B. Forbes and I were stranded at the Miami airport. The only way in was to charter a Lear jet, at the then exorbitant price of $3000; I remember calling Jim Millstone near midnight and how impressed I was that he said go ahead—and that he would take the heat if anyone at the office complained. “Get the story,” Jim said. “And it had better be good.” (A fear years later Margie Freivogel, then the nation/world editor, had much the same reaction when I called from the wartime Balkans, saying that Avis had agreed to give me a rental car only after I put a $20,000 deposit on my Post-Dispatch American Express.)

Long before my era, the Post-Dispatch had opted against opening foreign bureaus, on the quite sound reasoning that those dollars could be more effectively deployed on deep-dive coverage of issues as they arose, across the nation or around the globe. That strategy resulted in extraordinary original reporting, from Southeast Asia to the Middle East to Central America. From my own experience what sticks out are three months-long assignments:

Summer 1989 in Eastern Europe, as that region was miraculously breaking away from the Soviet Union. In Prague I got to interview dissident Vaclav Havel in the kitchen of his apartment, just after his release from prison. He was debating with colleagues whether to stage a march commemoratings the August 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. Havel said no, that a march would only expose their thus-far limited public support, especially in contrast to the Solidarity movement then on fire in next-door Poland. Four months later Havel was president of the country.

Summer 1990 in South Africa, in the months after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison and the suddenly dawning thought that the country’s future might be something other than racist apartheid forever. I was paired with Post-Dispatch photographer Odell Mitchell Jr. Our biracial team gave us access to, and insight on, townships and white enclaves that would have been impossible for either of us traveling alone. One Conservative Party couple in the Transvaal reneged, after seeing Odell, on an invitation to spend two days on their tobacco farm. They eventually agreed to limited access, grudgingly—so long as Odell didn’t enter the house. The result was a memorable feature story and photos on the “white dinosaurs” of South Africa. The couple didn’t like the story but four years later, when Odell and I returned to cover Mandela’s election as president, they invited us to dinner.

Fall 1991 in the Soviet Union, traveling across Russia, Ukraine, and the three Baltic states as the republics that made up the Soviet Union began to break away. The series of articles were titled “Awakenings” and they told the story of people coming alive to their own histories—and to possibilities they had dismissed for decades as unachievable. The report from Kiev, notable in hindsight given the realities of 2025, ended with a Ukrainian parliamentary leader telling me not to expect Ukraine “to march in lock step with Moscow. That day is gone.”

The National Press Club named each of those projects as winners of its prize for best foreign reporting. They succeeded, in my view, because the Post-Dispatch allowed months of preparatory research ahead of travel. It gave us what was essential—time on the ground ahead of filing to assure command of the material. It encouraged us to capture not just the big political news of the moment but the social, historical, and economic contexts behind societies in profound transition. That approach was rare in the 1980s and 1990s, rarer still in the journalism of today.

Press failures after 9/11

In my mind the biggest test of journalism independence, bigger even than the challenges we have faced under the presidencies of Donald J. Trump, came in the months between the 9/11 terrorist attack in September 2001 and the U.S. invasion of Iraq in March 2003. It’s a test that journalism, by and large, failed. The lessons from the experience had a huge influence in structuring what became the Pulitzer Center, as a trusted source of the multiple perspectives that are the essential prerequisites to informed debate and sound policy.

Amid the fractured politics of today it is hard to recall how united this country felt, in the awful days after those hijacked jets crashed into the World Trade Center towers, the Pentagon, and that field in Pennsylvania. President George W. Bush’s approval ratings hit 90 percent after the attack, the highest recorded since polling began, and remained at 60 percent or above through the spring of 2003.

Bush used that popularity to push through a war of choice, the invasion of Iraq, based on what turned out to be the false assumption that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction. He was joined in that assumption not just by his own Republican party but also a majority of Democrats, experts from the Clinton administration, and think tanks from the right and left.

Yet the fact that there was a consensus didn’t make the consensus correct—and journalism very much let us down, public and policy makers alike, by not pressing harder to test those pre-war assumptions. Instead of probing for inconsistencies, testing the evidence, we became an echo chamber—reflecting uncritically the views of administration officials, Iraqi exiles and others with a vested interest in bringing on the war.

Worse still, it was the most prestigious of our media outlets and personalities that led the way. Judy Miller’s uncritical reporting of bogus claims as to Iraqi weapons programs will forever shame The New York Times—yet Thomas Friedman’s beating the drums for war in his columns, coverage by the Associated Press, and editorials in The Washington Post weren’t much better.

There were exceptions, reporting that burrowed into the lower ranks of the CIA and Pentagon and State Department where there were deep misgivings about the prevailing view. Among the best were stories in the fall of 2002 from the Knight-Ridder Washington bureau, contending that the case for Saddam Hussein’s ongoing weapons programs was extraordinarily weak, for the most part based on defectors long absent from the country and evidence that was by then years old.

But again, these were the exceptions, and rare. Far more common, and influential, were stories like that which appeared on the New York Times front page in September 2002, asserting that Saddam’s “dogged insistence” on pursuing WMD had brought the two countries to the brink of war—and warning, in the words of an unnamed administration official, that “the first sign of a ‘smoking gun’ may be a mushroom cloud.” Condoleezza Rice and Dick Cheney both used that phrase, and were later criticized for gratuitously inflaming public opinion—but it was The New York Times, our best newspaper, that put those incendiary words in circulation first.

If you look back at media coverage of Iraq in 2002 and early 2003 it’s a blur of comparable exaggeration, mixed in with breathless reports of war preparations, escalating rhetoric, and a thoroughgoing demonization of Saddam Hussein as a totalitarian megalomaniac on the scale of Stalin and Hitler. What you didn’t see was much in the way of reporting from Iraq itself. No American journalists were based in the country during 2002 and few were even allowed to visit, with the exception of one- or two-day excursions on the occasion of Saddam’s birthday or for the sham plebiscite in which he received a nearly 100 percent endorsement.

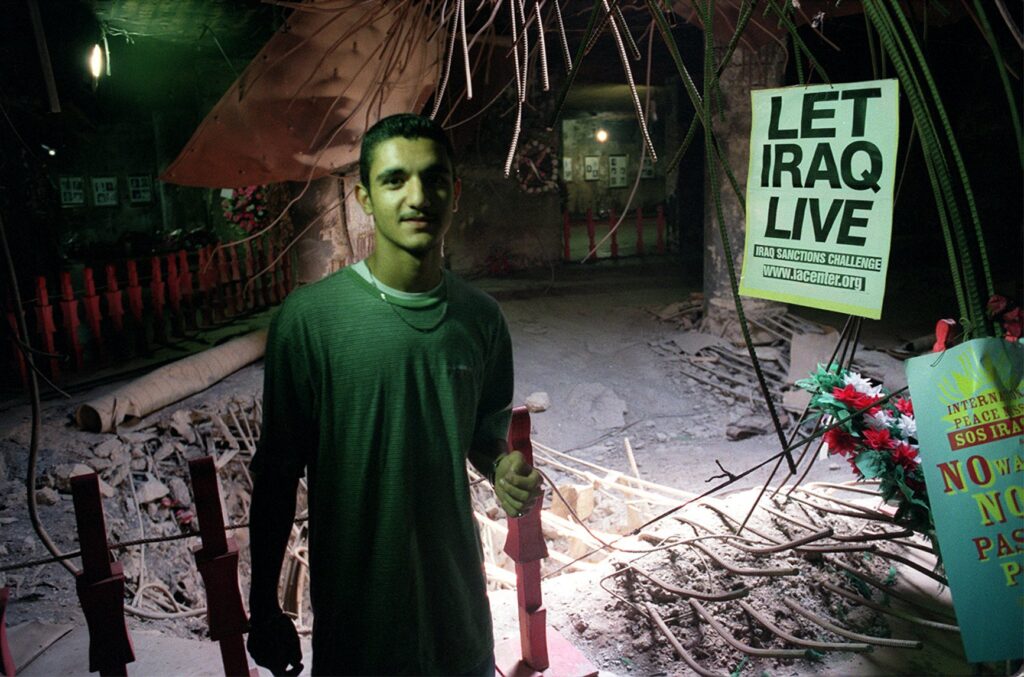

The situation in Iraq looked rather different on the ground, as I discovered in May 2002 when I had the opportunity to spend 10 days traveling in the country. What I found was sharp criticism of Saddam, even contempt, but also deep concern that a U.S. invasion would be a disaster—for the people of Iraq, for the broader Middle East, and for the United States. In subsequent reporting trips that fall and in early 2003, from Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Lebanon, as well as a follow-up trip to Iraq, I heard and reported the same. And yet the war came, at untold cost in lives and dollars and to America’s standing across the globe.

The lesson to me was that we could not count on elite news media outlets to give us the comprehensive reporting we need for truly informed debate. Major regional newspapers like the Post-Dispatch, for decades a reliable source of independent reporting and a vibrant supplement to the national media, were in rapid decline. To get the full range of perspectives required us to act proactively, to create a new approach. Thus the kernel of the idea that drove the establishment of the Pulitzer Center, and of like-minded non-profit news organizations across the country.

From a donated desk to a $1 million budget

For the Pulitzer Center it started in January 2006. There was a donated desk and half an office at the World Security Institute, a Washington non-profit led by my friend Bruce Blair. There was also $1.2 million in seed funding—from Emily Rauh Pulitzer and David and Katherine Moore, members of the Pulitzer family and major shareholders in Pulitzer Inc., the publishing company that had been sold the previous year to Lee Enterprises.

The seed funding was intended to cover four years of support, with the hope that by then we would have established proof of concept and be in position to attract additional foundation and individual support. By December 2009, the end of that period, we were well on our way: 100 reporting projects, a full-time staff of 11, and our first annual operating budget in excess of $1 million, nearly half of it from non-Pulitzer family sources.

Starting from scratch we had the advantage of learning as we grew: Setting up accounting and audit systems, hiring staff, incorporating as an independent 501(c)3, and embracing the two most important rules of operating any non profit: that the job of raising money never ends and that every “No” is prelude or practice to an eventual “Yes,” at some point somewhere down the road.

In the years that followed our own growth accelerated, thanks in part to major multi-year grants from the Kendeda Fund (including a matching challenge grant toward creation of a reserve fund), the Gates Foundation (in support of our global health reporting), and the MacArthur Foundation (a five-year commitment in general operating support). In 2016 Emmy Pulitzer made a major challenge grant, matching $12 million in donations from others toward creation of an endowment; it took us five years but we got there, with significant support from our board members Betsy Karel, Joe Pulitzer, William Bush, and Richard Moore, who succeeded his mother Katherine on the board after her retirement. Two additional challenge grants from Emmy Pulitzer since have further buttressed our endowment, giving us a stream of guaranteed annual income and financial reserves that are rare among journalism non profits. In 2024, my last year as CEO and president, we reported an operating budget of $12.3 million, more than 200 reporting projects, and full-time staff totaling 60 individuals in 16 countries.

How did that happen? When I look back I think of certain key traits that became characteristic of the Pulitzer Center, traits like collaborative, opportunistic, innovative, engaged, and adaptable. Many of them were evident on our very first project, a reporting trip I did in early 2006 from the civil war then raging in Sudan’s western province of Darfur.

The World Security Institute at the time was producing “Foreign Exchange,” a PBS program hosted by Fareed Zakaria that was precursor to his show on CNN today. The program was primarily interviews by Zakaria but also included short video reports, mostly by free-lancers, that were commissioned and edited by WSI.

I had obtained a travel permit to Darfur at a time when almost no western journalists were getting in. Steve Sapienza, a Foreign Exchange producer (and today a Pulitzer Center colleague), told me the reach of the reporting would be much greater if I did video as well as print. He helped recruit Abdul Nasser Abdoun, an Egyptian cameraman based in Khartoum, to make the trip with me, and then spent many hours working with me to turn 20 hours of footage into a four-minute segment for Foreign Exchange and a 20-minute documentary version.

Having that video material made a huge difference, especially at a time when Darfur was a major issue on American college campuses. We organized a special screening and panel discussion at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum that featured the ambassador from Sudan, senior government officials, and Samantha Power, author of the best-selling book on genocide, A Problem from Hell. We also arranged to air the presentation live at more than two dozen universities across the country that had access to broadcast-quality internet connections.

It was the first video I had ever made. The outreach across multiple campuses and cities was light years ahead of anything we had done on previous projects at the Post-Dispatch. It brought an important story to tens of thousands of people. And it was accomplished, on the outreach side, at virtually zero cost.

Small wonder, then, that video and photography became an integral part of the Pulitzer Center model, from the early work with Foreign Exchange to the dozens of projects since with PBS NewsHour and documentary projects across the globe. Or that several of the universities who invited me to speak that spring became charter members of the Campus Consortium we launched three years later, with universities covering the costs of bringing Pulitzer Center journalists on campus and giving students the opportunity to work with the Center on their own reporting projects. The high school discussions we led in St. Louis became the forerunner of a K12 engagement program that has now reached every state.

I don’t think any of us had any inkling, back in 2005, of the role the Pulitzer Center would come to play. Projects supported by the Center have won every major journalism prize, with topics ranging from migrants making the desperate crossing of Panama’s Darien Gap and civil war in Yemen to China’s suppression of its Uyghur minority and the global fight to end HIV-AIDS.

More important than prizes is the way we’ve broken new ground.

Importance of multimedia

The short video reports that blossomed into full-length documentaries. The idea of making poetry a medium for our reporting, first on HIV-AIDS in Jamaica and then on post-earthquake Haiti. Those projects mushroomed into multimedia web presentations, the commissioning of original music, performances in Port au Prince, and at the National Black Theatre Festival — and also our first Emmy, for new approaches to news and documentaries.

Those new approaches have been a hallmark of Pulitzer Center work since—from college reporting contests with YouTube to circus performances by Indigenous Canadians, the 10-city tour of the play we produced on solitary confinement, art exhibits in Bangkok, comic books introducing Congolese high schoolers to the reality of climate change, and the curricular resources we deployed in thousands of schools for “The 1619 Project.”

On 1619 our role was strictly on the outreach side, as the education partner recruited by The New York Times Magazine to help engage student audiences with the landmark set of essays led by Nikole Hannah-Jones, reimagining the role and impact of slavery in American history. Six years after its initial publication (and after release of two companion books plus a documentary series) it remains a topic of fierce debate, the focus of critiques by eminent historians, and attempts by Trump and others to make it a cultural wedge issue as to what can and should be taught in schools.

The 1619 Project wasn’t perfect, as The Times itself has acknowledged. Journalism rarely is. But the larger point, slavery’s central role in the shaping of America and its continuing legacy today, is beyond dispute. So too the egregious misrepresentations of slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow that were the stuff of standard history textbooks in this country for generations.

One of the most moving experiences for me was the opportunity to interview Hannah-Jones in a school assembly at R.J. Reynolds High School in Winston-Salem, N.C. In preparation for the visit students from history, art, dance, and other classes had engaged in the lesson plans we had written; on the day of Hannah-Jones’s visit they lined up to share their work.

“To say that moment was powerful doesn’t do it justice,” said Pam Henderson, the arts magnet director at Reynolds. “Our silent students, our quiet artists, our outspoken activists—they flocked to her, as she was a voice that spoke loudly to them. They created art inspired by her work and by the work of others taking part. They had conversations with family and friends, broaching topics often glossed over. They were brave because they were witnessing bravery and unapologetic inquiry.”

I was a student at Reynolds in the late 1960s, at a time when Black students numbered in the low dozens. My mother, as a member of the local school board in the 1970s, helped lead the fight to bring true integration to that school system, thanks to a mandatory busing program that at its peak included nearly 40,000 students.

Within a decade the busing initiative was dead, the victim of white backlash, conservative court rulings, and a federal government that turned its back. Today’s Reynolds is a predominantly Black school, and the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County schools are among the most segregated in North Carolina.

On the evening of her appearance at Reynolds, Hannah-Jones spoke to an overflow and diverse audience of nearly 1,000 people at Winston-Salem State University. She gave them an appalling litany of discrimination today, especially as to the yawning gap in advanced-placement and other educational programs between predominantly white schools in my hometown and those that are predominantly Black.

“Part of this conversation may make you feel uncomfortable,” Hannah-Jones said that night.

“I certainly hope it does.”

The 1619 Project and the curricular materials we’ve produced are not the final word in a debate that will no doubt go on. But against the backdrop of so much mis-teaching of American history they are a welcome corrective, and overdue.

Another period of expansion, globally

The 2019-20 period also marked a major expansion, and pivot in approach, for the Pulitzer Center.

First came the biggest institutional grant in our history, a five-year commitment for work on threats to rainforests worldwide from the government of Norway. It was this support that allowed us to hire accomplished editors, educators, and outreach specialists from each of the rainforest regions—and to begin the transformation of the Center into a truly global organization. (It helped hugely that in the first year of the rainforest initiative we recruited executive editor Marina Walker Guevara; as managing director at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists she had led the Panama Papers project, the biggest global reporting collaboration in history.)

Second was the Covid pandemic of 2020-21, a global health catastrophe that led to office closures, travel bans, and a complete upending of business as usual. We put out a special call for reporting on Covid, funding some 75 projects over the course of the year and many of them in partnership with journalists and news organizations based in countries that because of the pandemic were no longer accessible to reporters from the United States. With our own staff now working remotely we also embraced a policy of recruiting for talent worldwide; between 2020 and 2023 our staff nearly tripled, from 23 individuals all based in Washington to 60 individuals working across the United States and in 15 other countries.

In 2020 Norway doubled its support, funding the creation of a Rainforest Investigations Network that has given full-time stipends to nearly a dozen journalists a year, each of them working for separate outlets on their own projects but on the lookout for collaborations and together taking advantage of data-scraping and other research tools as taught by Pulitzer Center staff and outside partners. Norway has since funded a similar initiative on oceans, transparency, and governance.

We followed the same approach, with funding from others, on the AI Accountabilty Network we launched in 2022 and on StoryReach U.S., a fellowship launched in 2024 for journalists at local and regional outlets with an emphasis on both enterprise reporting and creative strategies for audience engagement.

For the past decade, of course, we have attempted to steer our journalism and engagement venture through the fraught and fractious time of Trump.

I mentioned earlier that I am less anxious about restrictions on press coverage today than I was in the early 2000s. That may appear counter intuitive, given Trump’s aggressive attacks on journalists as “enemies of the people,” the restrictions he has imposed on press access at the White House and the Pentagon, and the multi-million dollar settlements he has extracted from media conglomerates unwilling to contest libel suits that were laughably thin. Yet those restrictions notwithstanding we continue to get robust watchdog reporting, some of it from still-strong legacy news outlets and an ever-increasing amount from new outlets (Politico, Semafor, etc) and from the many individual journalists who have found a home, and followings, on platforms like Substack.

The difference in the early 2000s, in the national trauma of the post-9/11 months, is that back then it was journalists themselves, for the most part, who chose not to challenge consensus views: that Iraq was a war of necessity, for example, or that railroading young American Muslims through slipshod trials was an acceptable price to pay for ensuring national security. It wasn’t until the war itself began to go south, and until Democrats re-emerged in opposition, that journalism resumed, in general, a more critical stance.

The challenge today is different—that so many journalism outlets, legacy and new platforms alike, are pegged to one political side or the other. The business models are based on playing to, and inflaming, the pre-existing biases and prejudices of their own chosen choir. It’s a model that works, as far as building a large (and angry) audience. In terms of building bridges, promoting policy solutions, finding common cause? Not so much.

Crossing bridges of partisan division

The Pulitzer Center was built on the premise that we can cross those bridges, surface multiple perspectives, use art and theater and educational institutions as the springboard to conversations that inform and engage. Placing our stories in hundreds of different outlets, from the biggest global brands to community radio in the Amazon and Congo basin, is part of that strategy. So too an audience-centered approach to engagement focused on finding people where they are.

It helps that we are global in scope, with colleagues on staff who are engaging with authoritarian trends in their own countries, suffering from comparable collapse in old news-media models, and equally subject to epochal challenges like climate, AI, and more. They help us root our work in their expertise, their life experiences, their insights into potential policy solutions that might actually work.

One last big, and personal, lesson from the past half century plus in journalism: Coming to the realization that if you’re truly committed to the long-term sustainability of an organization then at some point you have to step aside—making way for new leadership and giving those leaders the freedom to set their own course. In my case that meant an end, as of June 2024, to day-to-day management responsibilities at the Pulitzer Center. I stay engaged, as the Center’s senior advisor, but only as a sounding board to Lisa Gibbs, our capable new CEO, and to the board of directors.

In the months since the Center has gone from strength to strength. It remains a global leader in reporting on climate, the oceans and other environmental issues. It has established an unparalleled program of grants, fellowships, and training for reporting on, and with, artificial intelligence. Our global team of engagement specialists pair our journalism with art exhibits, university partnerships, and K12 curricula, from Bangkok to Manaus and from Kinshasa to St. Louis.

I don’t pretend that the Pulitzer Center will or could, by itself, solve the immense challenges facing journalism, let alone the larger crises we face. I do think we are engaged in the effort—testing new approaches, forging new alliances, and hopefully serving as model and inspiration for all the groups working so hard to bridge the many divisions in our country and world. We are out there, trying.

I’m reminded of an early attempt at writing a news feature, at the Post-Dispatch. We were still working on typewriters, with clerks running the copy a few paragraphs at a time to editors across the newsroom.

The feature was about a mid-winter excursion to the Illinois River in Peoria, testing use of a British hovercraft to break up ice and get an earlier start on the shipping season. My lede on the story was one of the lamest ever, something along the lines of “The experience of being on a hovercraft when the engines roar to live and the vessel lifts above the river is something that’s impossible to describe.”

A few minutes later the copy boy brought my lede back across the room, this time with a big red grease-pencil circle around the offending graf. “Jon,” the scrawled note said. “It’s our job to try.”

Jon Sawyer founded the Pulitzer Center in 2006 and served as its CEO and president. He became the center’s leader after a 31-year career with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.