BOURBON, MO. — The Bourbon public library is small, with only one room housing a table with a puzzle, another with a few desktop computers, and three others for children’s activities and browsing. There is no LGBTQ+ section, no women’s studies, and a thin offering on racial studies. There is, however, a plethora of religious texts and Christian fiction.

The library doesn’t overtly censor books, and when I first walked into the building, one of the first titles I saw was the frequently banned graphic novel “Maus.” A Bible is propped up on display in the religion section, but so is the Quran.

Still, this library became the epicenter of a statewide scandal after a librarian was fired for refusing to remove a “Read with Pride” display featuring queer stories and authors.

Bourbon is a small town in Crawford County, Missouri, that spans 1.3 miles with a population of 1,694 people. Most of the town’s businesses — including a bar/restaurant, a thrift store, a health food store, and a police station — lie along one main road. The library is just off this road, past the police department.

The library prides itself on being inclusive, with a diversity and inclusion policy in place from 2018. An excerpt from this policy reads: “Diversity and inclusion go beyond simple tolerance to embrace and celebrate individuality by developing practices that recognize and respect all people and their points of view.”

Despite the picture of tolerance the library paints with this policy, the district fired Rachel Rodman for creating the pride-related book display.

Rodman worked for the library for nearly a year, during which time she was the primary librarian in charge of creating seasonal book displays for both children and adults. A few of these displays included one for Lunar New Year, Diwali, gardening, and a few recognizing local authors. Out of all the displays she created, this was the only one that faced any issues.

Rodman said the Pride display wasn’t over the top and wasn’t meant to call so much attention to itself. A photo of the display, which Rodman provided to the Gateway Journalism Review, shows a piece of printer paper on a bookshelf with the words “Color our world with Inclusion” in large letters, followed by “Read with Pride” in a smaller font. The display contained several works of fiction that don’t appear overtly LGBTQ related on their covers but that feature queer plotlines and characters.

Among the books were “The House in the Cerulean Sea” by T.J. Klune, a fantasy novel tells the story of a magical orphanage with found family tropes; Romance novel “Red, White & Royal Blue” by Casey McQuiston that follows the prince of Wales and son of the President of the United States as they fall in love; And “Fourteen Days”, a collaborative novel of stories told between neighbors amid the pandemic lockdown, edited by Margaret Atwood.

“I didn’t go ‘Look at me! Look at me!’ and put it in anyone’s faces, because out here in rural areas, censorship is already really strong, and people have very strong opinions against a lot of things that are controversial all over our country right now,” Rodman said. “But in areas like Sullivan or Bourbon, Missouri, there’s a lot more that are anti- (things like) LGBTQ (rights), and it’s really disheartening to be in a community like that because you love your community and your small towns but at the same time, you know, some of those people just don’t value the same things that you do.”

Rodman noted that the display was for adults and not children, who had a completely separate and unrelated children’s display located in a separate part of the library.

To her knowledge, Rodman said no complaints were made about the display by patrons of the library, and a few of the books flew off the shelves. A few days after she put it up, however, she was left a note by her branch manager telling her to take it down, writing in parentheses something to the effect of “one death threat per lifetime is enough for me,” Rodman said.

This references an incident in the library’s past — before Rodman’s tenure — where the facility received threats over its content. Rodman was aware of this and said it was why she made the display understated and only for adults.

“I was trying to be inclusive to everyone, while also being respectful of the fact that there are strong opinions, and I knew that the library had problems in the past,” she said. “Four years ago, they got death threats after having a children’s story time reading a book promoting pride by way of, I believe it was about the parade itself, with two parents who were same sex parents.”

Rodman refused to remove the display and said the request made her livid, considering it was against the library’s own diversity and inclusion policies.

“I was hurt because I’m also an openly bisexual person, and I’ve been open about that in the entire year that I worked at this library; they were very aware that I was very pro LGBTQ. I was not quiet about how any censorship of this specific thing would make me feel, to my branch manager (or) to my program director,” Rodman said. “I couldn’t be complicit in something that meant so much to me and so much to so many other people in the community.”

Rodman grew up in rural communities, having been raised in Saint Clair, Missouri, and now living in Sullivan, Missouri. Still, she was surprised at the political pushback she received for the display.

“Before working at the library, I didn’t realize people really, truly tried to ban books,” she said.

Her firing from the library has made finding work difficult, and to work at another library, she’d have to uproot her family, which includes six boys, five of whom are now teenagers. As she looks for her next opportunity, she is studying Social Work at Maryville University.

“I am not going to stop fighting for people’s rights,” Rodman said. “For every person this has impacted in a negative way, I’m so sorry, and I hope one day things change. But in the meantime, I want to keep fighting for it.”

Facebook posts dug her grave

Rodman posted about the incident on Facebook, which she says likely dug her own grave. The next day, the Crawford County Library’s new director walked in and demanded that Rodman remove the display and asked her to resign. Rodman refused, and the director told her the issue would go before the library’s board.

Instead of the public meeting Rodman expected where the board would vote on whether or not to keep the display, the director showed up three hours later, asked her again to remove the display, and when Rodman refused, handed her a letter of termination.

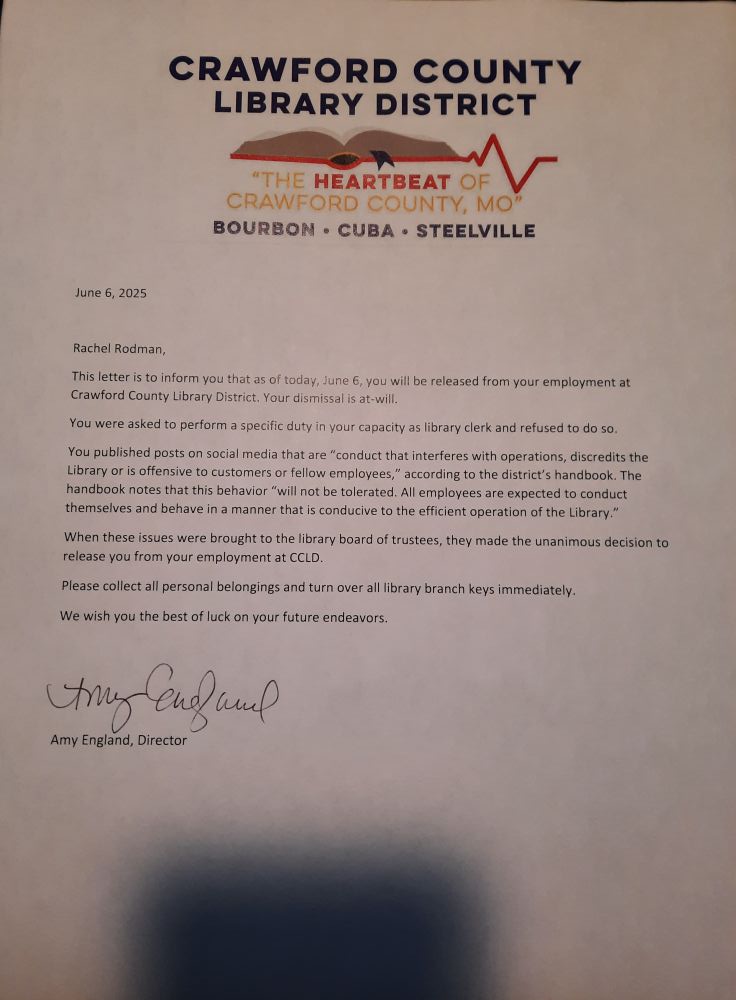

“You were asked to perform a specific duty in your capacity as library clerk and refused to do so,” an excerpt from the letter stated. “You published posts on social media that are ‘conduct that interferes with operations, discredits the Library or is offensive to customers or fellow employees,’ according to the district’s handbook.”

The letter said the Board of Trustees unanimously voted to fire her.

Amy England, the director of the Crawford County Library District, refused to comment on Rodman’s termination and instead issued a brief statement to GJR saying:

“We can assure you that we remain devoted to our policy of creating an inclusive, welcoming, and respectful organizational culture that appreciates and supports individual differences,” England said. “We will continue, within the constraints of the Library district budget, to select a diverse range of materials in a variety of formats to support the informational, educational, cultural and recreational needs of the population we serve. The Library provides a general collection of circulating materials embracing broad areas of knowledge, literature, and genres. Purchases are made to represent as many sides of current political, social, and cultural issues as possible. Included are works of enduring value and timely materials on contemporary issues. Collections are reviewed and revised on an ongoing basis to meet the needs of our community. We also will continue to embrace and celebrate individuality through our practices that recognize and respect all people and their points of view.”

Rodman’s firing brings to light the question of free speech rights for public employees, which has its roots in Illinois. While private employers have more freedom to fire employees for speech they disagree with, public employers are bound by the First Amendment.

In Pickering v. Board of Education, a Supreme Court case originating in Illinois, the court weighed whether a teacher was wrongly fired over his letter to a local newspaper criticizing the school board’s allocation of funds.

In an 8-1 decision, the Supreme Court reversed a lower court’s decision that had sided with the school, setting the precedent that public employees do not relinquish their free speech rights when accepting government-funded employment.

While the decision in Pickering helped establish the test courts use today to determine whether a public employee’s speech is protected, it doesn’t necessarily protect Rodman.

“The Supreme Court in Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006), ruled that public employees do not have a First Amendment protection for speech issued as part of their official duties,” according to the Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University.

While Pickering’s case was decided in 1968, a wave of new free speech concerns has come into the limelight for public employees following the assassination of right-wing political pundit Charlie Kirk.

While influencers on the Right as well as public figures with more moderate or left politics mourned Kirk’s death, others highlighted his problematic past, resulting in Vice President Vance encouraging an effort by right-wing influencers to dox and fire those critical of Kirk. One of the websites started for this purpose, “Expose Charlie’s Murderers,” has been taken offline after soliciting tens of thousands of dollars in Cryptocurrency, Reuters reported. Hundreds lost their jobs or faced other discipline from their employers for posting criticism of Kirk on social media and the U.S. State Department revoked the visas of at least six individuals who spoke up against Kirk.

In an interview with Fox News, Vance falsely stated that this criticism of Kirk should not be protected by the First Amendment, CNN reported after the interview.

“The First Amendment protects a lot of very ugly speech,” Vance told Fox News. “But if you celebrate Charlie Kirk’s death, you should not be protected from being fired for being a disgusting person.”

When determining whether a public employee’s speech is protected under the First Amendment, courts weigh whether the employee is speaking as a private citizen or in their official capacity.

Free-speech advocacy group FIRE said “Pickering and its balancing test applies when the employee speaks as a citizen on a matter of public concern.”

“The Supreme Court instructed in Connick v. Myers that it is anything ‘relating to any matter of political, social, or other concern to the community,’” according to FIRE. “And courts will decide this issue based on ‘the content, form, and context of a given statement.’”

Midwest the center of nationwide censorship

Over the past several years, a rise in book banning attempts in libraries and schools across the country has made headlines and fueled heated school board meetings in districts both large and small. Experts say the viral nature of this issue and increasing societal polarization has led to many schools and libraries pre-emptively censoring their shelves.

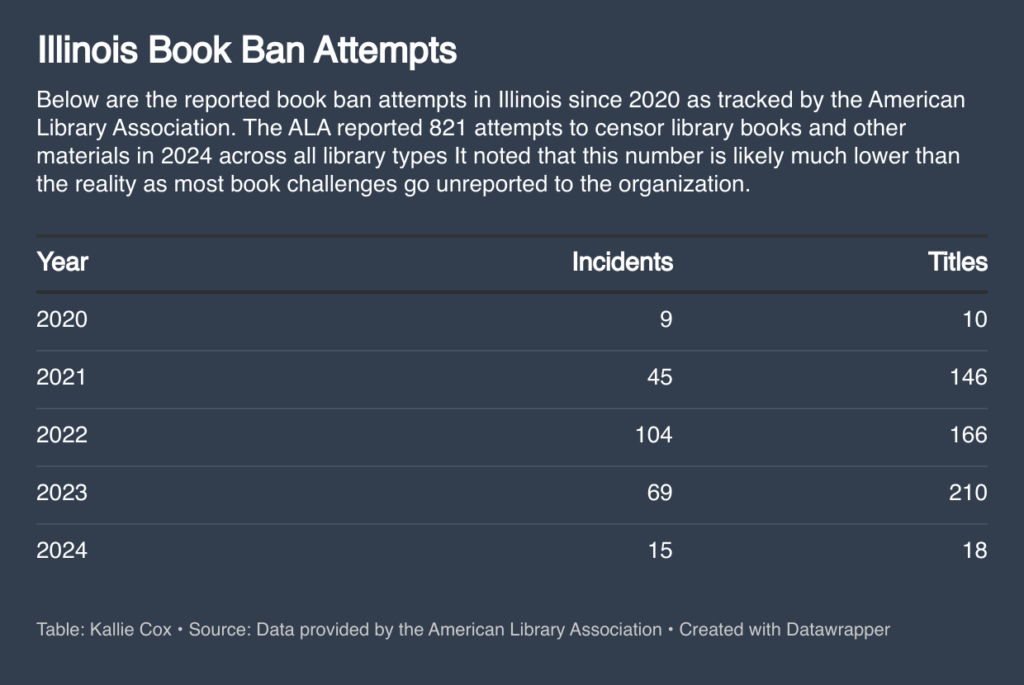

Although 2024 saw a slight decrease in reported censorship attempts, the number of challenges remains historically high.

Reports sent to the American Library Association documented 821 attempts to censor library books and other materials in 2024 across all library types, a decrease from 2023 when 1,247 attempts were reported, the organization stated. It noted that this number is likely much lower than the reality as most book challenges go unreported to the organization.

ALA President Sam Helmick said 2025 is on par to match 2024 in-terms of censorship attempts as of the organization’s latest data.

“We’re really shocked to see that this number continues to be significant in consideration to all of the attempts that have been taking place in the last three to four years,” Helmick said. “You would think that there would be a break or a crest in the wave, and the wave just sort of keeps coming.”

Helmick said there seems to be a consistent pattern in the titles that are targeted for censorship.

“Authors of color, stories about queer characters and then topics that are sometimes divisive in our nation — so things such as climate action or social justice — are being targeted,” Helmick said. “And the problem with that is that they’re also by pattern, followed by attempts to dismantle or defund libraries as publicly funded institutions.”

This threat of funding cuts hangs especially heavy over the heads of small and rural libraries. One of these libraries in a small Missouri town recently came under scrutiny after it fired a librarian for refusing to remove LGBTQ books from display.

The chilling effect

The Crawford County Library District is just one of many institutions that is complicit in what experts call “obeying in advance,” which means pre-emptively censoring books and displays before they can be challenged.

Helmick said this chilling effect is causing librarians to think twice about the titles they choose to order and display. The ALA calls this “censorship by exclusion,” where librarians are prohibited from purchasing certain books. Censorship by exclusion, alongside underreporting and legislative restrictions, are three of the reasons the ALA suggests overall ban numbers may be down year over year, but the challenges to library materials remain prolific.

“With library workers increasingly harassed or castigated or characterized in very unattractive and cruel ways, you’ll see that there’s like this form of self censorship or chilling. You start to worry that if you purchase books that you would have purchased before, you may unwittingly cause a dispute or some chaos in your home community,” Helmick said. “So it makes you think twice about the work that you were called to do, to amplify and uplift and champion all kinds of stories to give your community the most robust and wide variety of information possible.”

PEN America, a writer’s organization, said the impact of state-sanctioned school book bans are difficult to calculate because of a lack of reporting and different terms and restrictions used when removing books from a school shelf. Still in the 2024-2025 school year, PEN recorded 6,870 instances of book bans across 23 states and 87 public school districts.

The states that led the nation in these bans were Florida (2,304), Texas (1,781), and Tennessee (1622).

Although these numbers are higher than they would have been several years ago, some courts are protecting access to books. Recently, in Missouri, a Jackson County Circuit Court Judge struck down the state law “criminalizing school employees for supplying ‘sexually explicit material’ to students, ruling it unconstitutionally vague and overbroad, according to the Missouri Independent. Advocates challenged the law after hundreds of titles were removed from shelves.

Illinois protects books

As of 2023, Illinois Public Act 103 “bans book bans” and prohibits the banning or restriction of specific titles and resources from public libraries. The law was set to take effect in 2024 and Capitol News Illinois reported it as a “first-in-the-nation law,” that tied state funding to the adoption of the ALA’s Library Bill of Rights.

By contrast, as of 2023 when Illinois was adopting its landmark law, Missouri had the 3rd highest number of banned books nationwide, according to a report by free speech organization PEN America.

Christine Emeran, the Youth Free Expression Program Director for the National Coalition Against Censorship, said many of the books that are facing challenges across the country can be tied back to state laws and conversations surrounding Diversity Equity and Inclusion or Critical Race Theory. They are also tied to claims of appropriateness and obscenity, a conversation that often overlooks that parents have always had the right to opt out of specific reading material within their school’s curriculum.

“It started (in) 2017 when Trump had an executive order against indoctrination, and from that point on, it trickled down into states creating laws that were combating (…) what we call now DEI, or (…) CRT, and those basically were books from people of color talking about issues, political, social issues,” Emeran said.

These stories ranged from discussions of policing to being part of the minority in a majority white school, she said.

“Those types of stories were being challenged for removal because it made the majority uncomfortable,” Emeran said. “It made the adult majority uncomfortable, less so than probably the children.”

Students are concerned about the bans because they feel ready to tackle the social issues that the books delve into, Emeran said.

“Not talking about it, it brings shame, embarrassment, especially if you are from those communities or the topics impact you,” Emeran said. “It gives you the impression that there’s something wrong with you.”

In the beginning, Emeran said that challenged books would return to the shelves about fifty percent of the time. Now, coordinated attacks challenging hundreds of titles at a time are completely changing the censorship landscape.

“It really is a completely different phenomenon, because these are lists of books that people are receiving through the internet and they’re using similar tactics to challenge these particular books,” she said.

This is in line with what the ALA is observing and the organization reported 72% of reported censorship attempts are from pressure groups and government entities.

The viral nature of these bans that have exploded in coverage thanks to conservative organizations such as Moms for Liberty — who ignored several requests for comment on this story — is causing librarians to fear for their safety and mental health.

Librarians are being harassed and falsely called “groomers,” and “pornographers,” for working in libraries that contain books patrons feel are inappropriate, Emeran said.

“What’s difficult is that libraries are increasingly being called to support the information gaps that exist in our society,” Helmick said. “At the same time, the work that they’ve done to inform our society and to uplift our democratic republic is being attacked with a vitriol that is actually unmatched. I think this far exceeds the McCarthy era at this point.”

Despite the increasingly polarizing world of book bans, Helmick and Emeran are seeing signs of hope in communities that choose to push back against censorship.

“When students and community members go to board meetings and talk about the value of these particular titles, the books, they are more likely to have success in overriding the challenger to the book,” Emeran said.

Rodman also sees the value in creating a community free of censorship, even though with six kids to raise it cost her her job.

“The entire point is that we are supposed to create communities. We’re supposed to support those people in those communities, and not just some of them, but all of them. And if it’s a taxpayer’s money paying for it, then I’m sorry, but all taxpayers count, regardless of what orientation they have, what religion they have, what race they have.”

Kallie Cox is a St. Louis-based journalist and a graduate of Southern Illinois University Carbondale. They are a contributing writer for the Gateway Journalism Review and a member of the Trans Journalists Association.