Unintended consequences often prove fruitful.

Sports Illustrated’s recent series of articles chronicling cheating at Oklahoma State University were meant to reignite a long-running conversation about the seedy culture of big-time college athletics. Instead, Sports Illustrated started a conversation about credibility and perceptions of bias that overshadowed its original plan.

Sports Illustrated’s series consisted of five parts. Part one alleged illegal cash payouts to football players; part two alleged academic fraud; part three detailed reports of illegal drug use; part four concentrated on stories of sex between hostesses and recruits; and part five examined the lives of athletes discarded by Oklahoma State. The writers are Pulitzer Prize-winner George Dohrmann and Oklahoma native Thayer Evans. The investigation claimed to have lasted more than 10 months and included interviews with more than 60 former Oklahoma State football players.

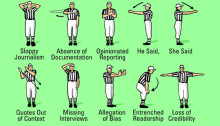

Sports Illustrated trumpeted its series with boasts of a searing look at the underbelly of a major football program. The results were something else. Backlash started almost immediately after the first part ran. Evans’ former co-worker and ESPN national sports columnist Jason Whitlock sent out numerous tweets disparaging Evans’ credibility.

He even went on Oklahoma radio and called him a “hack.” Former Oklahoma State quarterback Brandon Weeden accused Evans of a bias against Oklahoma State and relayed an interview he did with Evans, when Evans asked when his team would pull another “Okie Chokie.”

Then players who had been interviewed started recanting their stories. Multiple players told Oklahoma news sources they had been misquoted, or that their quotes had been taken out of context. Oklahoma media started poking holes in the Sports Illustrated series by questioning Evans’ credibility, and by reporting on the number of players recanting what was said (even though many said at least some recanting would be expected). News sources reported many of the players interviewed were players who had been kicked off the team, or left for multiple reasons. The focus of the series shifted, at least on the Internet, from Oklahoma State to Evans and Sports Illustrated.

More stories reported what was wrong with SI’s reporting than praised its efforts. National news media sources joined the chorus. ESPN and Deadspin both found mistakes in Sports Illustrated’s stories by doing some simple fact-checking and calling the school’s registrar to ask questions. They found that none of the professors in programs accused of academic fraud had been interviewed. A former SI fact-checker went on record saying that Sports Illustrated’s fact-checking was lacking.

At the same time, Yahoosports.com ran a story about Southeastern Conference football players receiving illegal benefits, complete with documentation and names. (http://sports.yahoo.com/news/ncaaf–documents–texts-reveal-impermissible-benefits-to-five-sec-players-202513237.html) This led to another hole in the Sports Illustrated story. The Sports Illustrated story took 10 months and had interviews with more than 60 people, but it had no documentation. It was one large “he said, she said” piece.

Compared to the article written by YahooSports, the Sports Illustrated series didn’t measure up. Interviews are crucial to an investigative piece, but there must be some form of documentation to support those interviews. Sports Illustrated never backed up its assertions, making the story completely about its own credibility.

This allowed opinion to become the major factor in deciding whether to believe the story or not. Evans defended his lack of a bias against Oklahoma State in an interview with Sports Illustrated.

Bias and perception of bias played a key role in the story. Readers who read the piece (and reporters who wrote about it) carried their own perceptions and bias into the story. Will Leitch wrote on www.sportsonearth.com that our perceptions have become so entrenched that the story seldom makes a difference on our opinions. In a story titled “Shock and Yawn” Leitch wrote (read his entire story at http://www.sportsonearth.com/article/60758436/): “One of the major lessons we’re learning about journalism in this day and age is that, no matter how high-quality the piece (a level of quality that far exceeds this one), you’re just not going to change anybody’s minds anymore. We are all entrenched. Something like this enters the public sphere, we all come out of our corners, take turns whacking at it, and then retreat to our corner. We always stay in our corner.”

Leitch’s argument that the audience is so entrenched in its own opinions and unable to change its mind is troubling. The Oklahoma State series serves as an anecdote that can be used to support Leitch’s opinion. Whitlock, who inserted himself into the narrative early by bashing Evans on Twitter (and later on Oklahoma radio), chimed in with his longtime argument that big-time college sports needs to change the entire “plantation” system that profits off the backs of athletes and discards them. The stories of cheating, through Whitlock’s eyes, miss the point altogether.

Others took what they wanted out of the piece and used that for their arguments. Some looked at the story with the jaded eyes of those who have seen this story done ad nauseum over the years and simply say, “So what?”

The efforts by Oklahoma media to discredit the story, or to point out major flaws in it, certainly played to readers with a pro-Oklahoma State point of view. While many in Oklahoma reported that at least some of the story must be believed, the stories were written for an audience that tilted pro-Oklahoma State. If a reader wants to take the time to look at all the articles written about this story, everything seems to come with a point of view. That includes the original Sports Illustrated piece.

That piece was not a nuanced story about a big-time sports program. The story came with an opinion and failed to mention the millions of dollars oil investor T. Boone Pickens invested in the program during the years Sports Illustrated was investigating. Too much was missing from the Sports Illustrated piece.

Sports Illustrated set out to tell a story about all that’s bad about big-time college football. YahooSports did the same thing by using travel documents to verify violations in NCAA football. Sports Illustrated took the wrong approach. Selling the argument that Oklahoma State became a big-time program through hundred-dollar handshakes, grade fixing, drugs and sex wasn’t going to work. It had all been said and written before.

What Sports Illustrated really did was open up a conversation about investigative journalism. Credibility still ranks as the most important tool a journalist can have, and damaging that credibility with a series that was opinionated (and old news to start with) was not in the best interests of journalism as a whole. Risking credibility to become the centerpiece of an argument that already has entrenched opponents leads to an unhappy ending. Risking that credibility at the same time another organization brings out a similar piece with documented proof is even worse.