On April 19, 1945 the New York Times published an obituary for nationally known war correspondent Ernie Pyle who “died today on Iejema Island, just west of Okinawa, like so many of the doughboys he had written about…killed instantly by Japanese machine-gun fire.” Pyle, the Times added, had become World War II’s beloved “chronicler of the average American soldier’s daily round, in and out of foxholes in many war theatres.”

On April 19, 1945 the New York Times published an obituary for nationally known war correspondent Ernie Pyle who “died today on Iejema Island, just west of Okinawa, like so many of the doughboys he had written about…killed instantly by Japanese machine-gun fire.” Pyle, the Times added, had become World War II’s beloved “chronicler of the average American soldier’s daily round, in and out of foxholes in many war theatres.”

He had also become the role model for journalists covering a war. After 1945, American reporters pursued that ambition in Korea in the 1950s and in Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s. But when Great Britain and Argentina squared off in their 1982 squabble over the Falkland Islands and during America’s first war in Iraq in 2003, government restrictions and censorship made it impossible. Thus reporters’ dreams of heroism on the field of battle or in the field of journalism came to an end.

“The age of the war correspondent as hero appears to be over,” Phillip Knightly, reporter for the London Sunday Times, wrote in his book “The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth-Maker from the Crimea to Iraq.” (2004 edition)

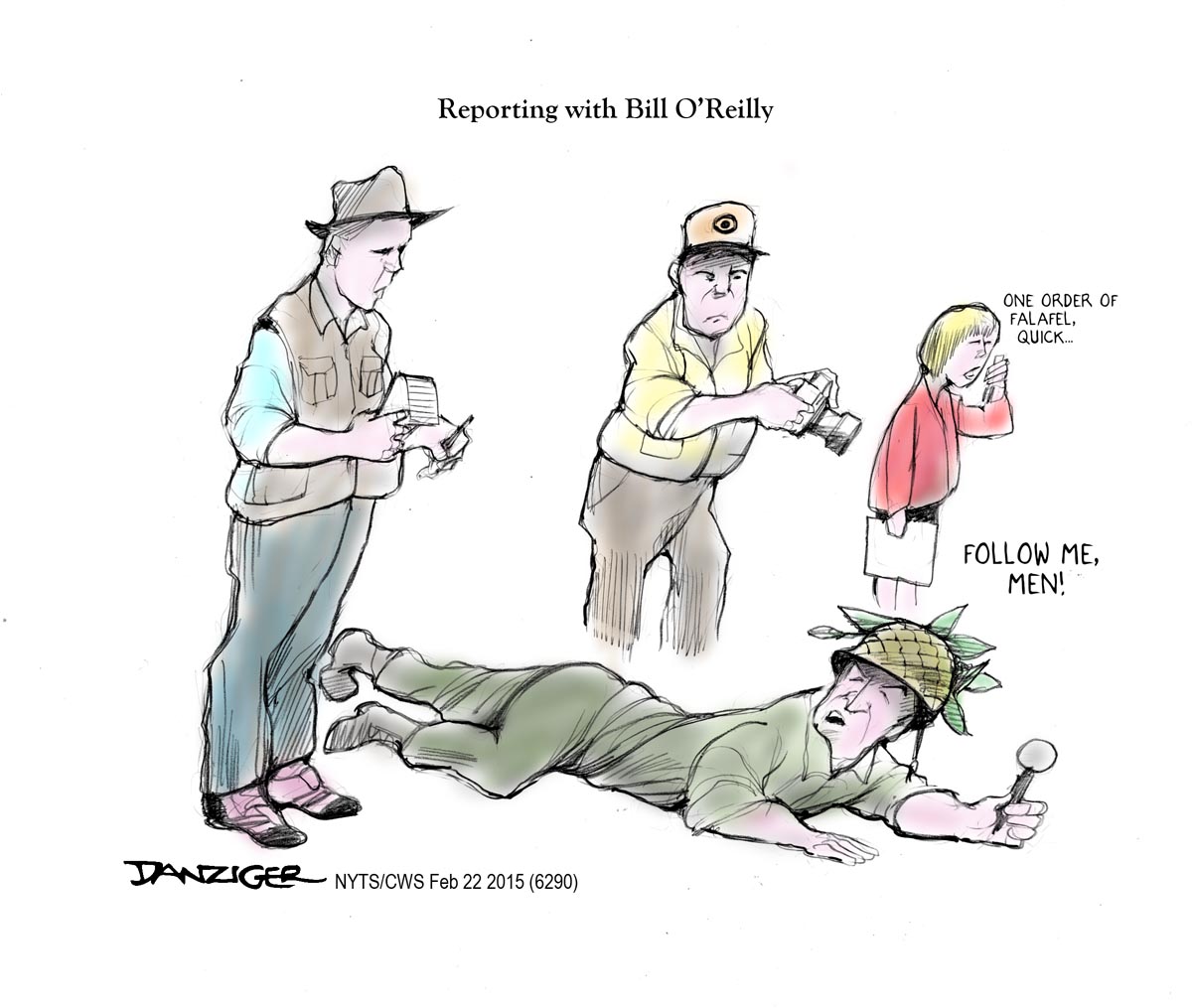

This is not an excuse for the embellishments of the experiences Fox News’ Bill O’Reilly made to his reporting on the Falkland Islands war or NBC’s Brian Williams to his stint in Iraq, but as context around their original claims, lost in much parsing of the phrases or terms with which they initially described their encounters with the dangers of covering frontline carnage.

The Vietnam War, Knightly wrote, was “better reported than any of the other wars examined here” (in his book). Drew Middleton, who covered the military for the New York Times, attributed that to the absence of censorship. As a result, there was a great deal of original reporting. Moreover, access to the population of Vietnam allowed reporters to capture the human aspects of the war’s “complete tragedy” for both sides. Seymour Hersh won the Pulitzer Prize for his stories about the My Lai massacre, Sydney Schanberg for his dispatches from Cambodia carpet-bombed by United States Air Force B-52s.

Reporters were free to write the first draft of history in Vietnam, and David Halberstam of the NYT expressed this in a letter to Knightly. He suggested that each story from the war there should have included a third paragraph that read: “All of this is shit and none of this means anything because we are in the same footsteps as the French and we are prisoners of their experience.”

The United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defence, a decade later, wanted to make sure reporters would not come to a similar conclusion about the Falklands conflict. Only a group of selected British correspondents were allowed to accompany UK forces to the battlefield on the islands, leaving “no room for impartial reporting.” O’Reilly and all other reporters covered the conflict from Buenos Aires, 1,180 miles from combat, based on press releases prepared in London.

The British government, Knightly observed, followed three rules: control access to the fighting; exclude neutral correspondents; censor your own. The American government found another way to prevent war correspondents from undermining its Iraq operation by the ways they might report it: it embedded reporters within units of American forces. They thereby saw to it that a bond was established between the members of the unit and the correspondent assigned to it; they controlled just what embedded reporters got to see and what they would not see.

Questions about the “big picture,” about the government-proclaimed progress made in the war were often brushed off during press briefings: “This is a f___ing war, asshole. No more questions for you. Why don’t you just go home.”

Reporters were embedded, caged in the experiences of their units, unable or unwilling to report on the plight of the Iraqi victims of the fighting. The media at home decided that the public was not interested, in 2003, in people just like those responsible for 9-11. The government had won the battle for the hearts and minds of the American people, even if lies about Iraq were necessary.

And for correspondents such as Brian Williams, the dangers a freely roaming reporter like Ernie Pyle faced in war zones, were unavailable, so he added them to his reporting repertoire.

What O’Reilly and Williams did was not necessary. The former is a leading talk show host, the latter a successful nightly national news anchor. Their climbs to those positions were, we assumed, supported by solid news reporting in the past, and if possible by the “heroism” of facing great danger to capture what the wars on the Falkland Islands and in Iraq were like for all touched by them, and what they were all about.

There has been little of that kind of reporting since it was squashed in the Falklands and in Iraq.

War reporting had become collateral damage of war.