Thirty-seven years ago, on Jan. 13, 1988, the U.S. Supreme Court announced a devastating blow to student speech and the student press when it ruled that the principal of Hazelwood East High School could remove controversial stories about teen pregnancy and divorce from the school newspaper over student objections.

The court’s decision in Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier was one of the most far-reaching decisions restricting free speech in the past half century. Even as the Supreme Court has recognized expanded free speech rights for corporations, makers of violent video games and fundamentalist picketers at veterans’ funerals, it has continued to limit the free speech rights of students in the public schools.

With today’s social media, Hazelwood’s restrictions on student speech can follow students back to their homes. Some courts have ruled that principals can punish students who write ribald comments or parodies on a home computer, if the comments disrupt the school.

Indiana University’s recent attempt to bar news from the storied Indiana Daily Student was a reminder that the decision still hangs over student journalists.

Will Creeley, legal director of The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression FIRE, said recently that Hazelwood remains one of most troublesome and restrictive Supreme Court free speech decisions and that some courts have tried to extend it to college media.

Gregory P. Magarian, the Thomas and Karole Green Professor of Law at Washington University law school, says Hazelwood “remains a very important speech-restrictive decision.”

“The court has put much more energy into expanding the free speech rights of politically or economically powerful speakers while largely disdaining the First Amendment concerns of politically and economically disempowered speakers,” Magarian said. “Through this lens, Hazelwood represents perhaps the most important instance of the court’s steady retreat from protecting students’ free speech rights.”

Mitch Eden, former adviser to Kirkwood High School’s Call newspaper, says “advisers all know of the damage done 25 years ago with the Hazelwood decision. There are too many schools today in which scholastic journalism is simply a public relations tool for the administration or, worse, being cut because journalism is not part of the ‘common core,’ the latest educational buzzword. Well, journalism is a field where the goal always has been … focused on excellence, on independent thinking and on leading, not following the crowd.

Eighteen states have passed New Voices laws to restore and protect the rights of student journalists. Those states include all of those surrounding Missouri – Illinois, Arkansas, Kansas and Iowa. Illinois has two separate laws, one protecting high schools and one colleges. The Missouri Legislature has considered the New Voices bill many times, but it has not passed.

Last-minute decision

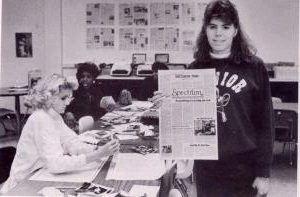

The Hazelwood East case began at the end of the school year in 1983, when the Journalism II class, which produced the Spectrum, compiled two full pages of stories under the headline: “Pressure describes it all for today’s teenagers. Pregnancy affects many teens each year.”

Principal Robert Reynolds objected to two of the six articles. One was an account of three Hazelwood East students who had become pregnant. The article made references to birth control and sexual activity and reflected the positive attitude of the girls toward their pregnancies. The other article was an account of a student whose parents were divorced. The student complained that her father often was absent, “out late playing cards with the guys.”

The names of the pregnant girls had been changed, but Reynolds was concerned that they could be identified from other information in the articles. The Spectrum planned to delete the name of the student in the divorce article, but the real name was on the proof read by Reynolds. Reynolds thought it unfair that the father did not have a chance to respond. The principal ordered the two pages removed from the Spectrum, excising four unobjectionable articles along with the two controversial ones.

Three students on the staff, led by Cathy Kuhlmeier, challenged Reynolds’ action. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union of Eastern Missouri, the students won in the federal appeals court in St. Louis. But the lawyers handling the case botched the argument in the U.S. Supreme Court, according to the recollections of former ACLU leaders.

The late Fred Epstein, past president of the ACLU, said in an interview a decade ago: “As I recall, Hazelwood was argued by a couple of incompetent lawyers who would accept no advice from the ACLU or other lawyers who had Supreme Court experience. Worst of all, the two ACLU lawyers handling the case would not even let friendly lawyers conduct a mock court to prep the two lawyers handling the case.”

Justice Byron White, who wrote a number of decisions hostile to the press, wrote the 5-3 majority opinion in which he said high school newspapers were part of the school curriculum, not public forums for the exercise of free speech.

“Educators do not offend the First Amendment by exercising editorial control over the style and content of student speech in school-sponsored expressive activities so long as their actions are reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns,” White said.

In dissent, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. said, “The mere fact of school sponsorship does not … license … thought control in the high school.”

Brennan added: “The young men and women of Hazelwood East expected a civics lesson, but not the one the court teaches them today.”

Weaker protection of the press

The Supreme Court’s weaker protection of free student expression is consistent with weak support on the court for the press in general, Magarian says.

“The idea of press rights, as a specific, separate category of free speech rights, has all but died on the vine,” he wrote. “That has more than anything else to do with changes in media economics and technology. But even before the Internet, the court had largely embraced an attitude toward press rights that was indifferent at best. Hazelwood is part of that.”

So are decisions where the court refused to extend constitutional protection for journalists to protect confidential sources and held newspapers responsible for abiding by reporters’ promises of confidentiality to sources.

Adds Magarian: “It is striking that the limitations on student rights and press freedom have come over a time when the court has expanded other First Amendment rights.”

But, he adds, “First Amendment speech rights haven’t simply expanded over the past 25 years. Instead, First Amendment speech rights have changed shape. The court has put much more energy into expanding the free speech rights of politically or economically powerful speakers while largely disdaining the First Amendment concerns of politically and economically disempowered speakers. On the other side of the ledger, we can see the court’s expansion of commercial speech rights – and, especially, its conversion of campaign finance regulation into a First Amendment preserve.”

In an interview with the Freedom Forum a decade ago, Kuhlmeier recalled a girl coming up to her at a symposium on the case and calling her a “freedom fighter” while asking for her autograph.

“I never thought of myself as a freedom fighter,” she said. “But I guess I did at least try to make a difference. Students don’t have enough First Amendment freedoms. There are a lot of very intelligent kids out there, and we should listen to them more. Maybe, if we did, the world would be a better place.”

William H. Freivogel is the publisher of GJR, the only journalism review left in the country that still produces a quarterly print magazine.