On July 4, 2023, Samuel Davis, a 26-year-old officer for the Northwoods Police Department in North St. Louis County, took Charles Garmon into custody at a Walgreens. After handcuffing Garmon, Davis drove him to a remote intersection outside of a Pepsi bottling plant in Kinloch, a now-largely industrial city of under 300 residents, some four miles and five municipalities from Northwoods.

Outside of the Pepsi plant, Davis pepper sprayed Garmon, beat him with a baton — breaking his jaw — and “told Garmon not to return to Northwoods,” according to a federal civil rights lawsuit Garmon later filed.

Rather than then transport him to any kind of facility where he could then receive treatment, Davis left Garmon in a field on the side of the road for someone else to find, leading to a 911 call, Davis’s identification, a warrant being issued, and his eventual arrest on felony assault and kidnapping charges two weeks later. (Davis’s supervisor, Michael Hill, was also arrested, and both have also since been indicted on federal civil rights charges.)

Within a few weeks, local TV station KMOV found that in his short career, Davis had already jumped to the Northwoods police from the North County Cooperative Police Department, something reporters found using a roster from that department.

“Tracking other departments Davis may have worked at isn’t easy in Missouri,” the station noted. “The state doesn’t have a central system for the public to see if an officer has moved around. The only way to know is to ask each department if an officer worked there.”

It is true that, unlike many other states, Missouri doesn’t have a system for the public or press to see if an officer has moved around. However, the Missouri Department of Public Safety’s Peace Officer Standards and Training Commission (POST), which licenses police officers in Missouri, is also required by law to keep track of their employment changes, which it does in an internal database.

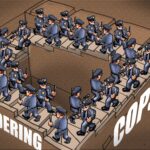

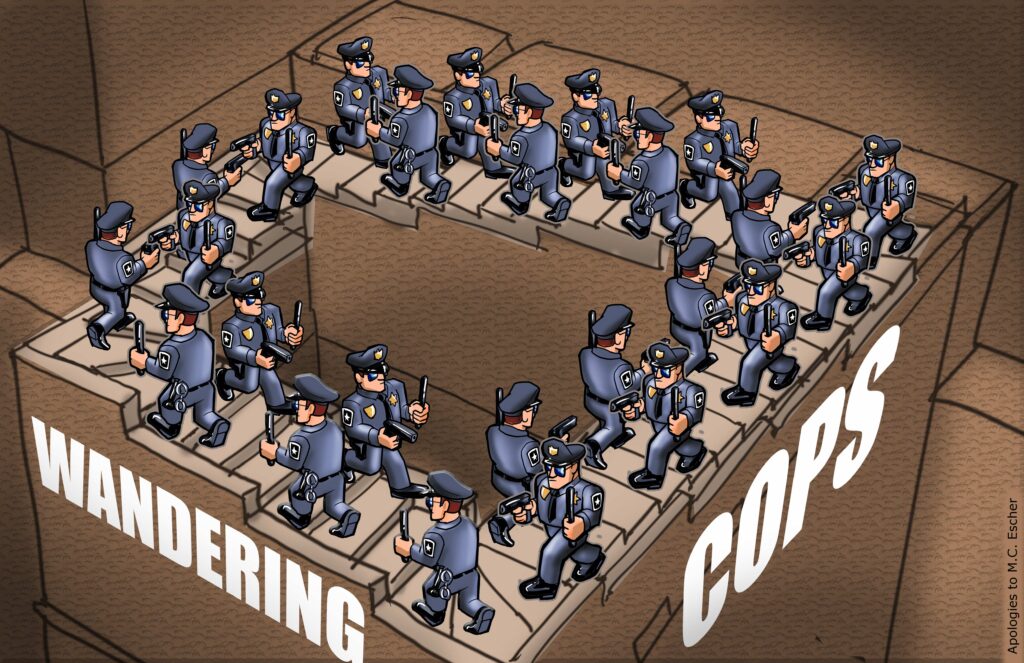

It’s a system that was instituted in large part due to a troubling history of department-hopping by officers in the St. Louis metro region, and a failure of oversight by the state — a problem often referred to as “wandering cops,” or locally as the “officer shuffle” or “muni shuffle.”

The shuffling of problem officers between departments has played a recurring role in police misconduct scandals in the St. Louis area since at least the 1970s, according to a review of official studies, newspaper investigations and archives, and interviews with experts.

While not unique to St. Louis, the region’s strikingly harsh history of using municipal borders and law enforcement to severely maintain racial segregation as Black residents began to move out of the city core led to particularly acute examples of violent cops being shuffled from one tiny department to the next — rather than being held accountable.

This practice became so infamous by the 1980s that it prompted a local law professor to successfully push for state police training boards across the U.S. to exercise greater oversight of local cops.

Many of those state training boards — 26 total — now release data showing the employment history of officers to allow for use by the public, press, researchers, attorneys, and others to quantify the problem of wandering officers that was first fully exposed in Missouri.

States around the country have released this basic data to a nationwide collaborative reporting project, including nearly all of Missouri’s neighbors. Illinois even publishes a simple lookup tool for police employment history.

Missouri, however, interprets state law as barring the release of the historical data that would show the public and press which officers qualify as wandering cops. Missouri POST restricts the data it releases to snapshots of what officers are active in Missouri and their current agencies at the time the information is requested.

Experts have called on the state to reconsider its withholding of this basic information.

“It’s hard to imagine data that would be more important or relevant for the public to have,” said Christy Lopez, a former Department of Justice official who led the federal consent decree investigations in Ferguson and Chicago, “and where the state would have less of an argument that that information shouldn’t be shared.”

Root causes

When news broke of Davis’s employment history before being hired by the Northwoods Police, John Bowman Sr., president of NAACP St. Louis County, placed him along the larger arc of policing in the St. Louis metro region.

“This has shined a lot on several things,” he told KMOV. “The fact that small municipalities are totally dependent on reject officers.”

A root cause of the “officer shuffle” is the same as many that plague the St. Louis region: the original sin of the contested 1876 vote that split the City of St. Louis from St. Louis County with a fixed border, and eventually allowed for the agglomeration of the tiny postage stamp-sized municipalities with the power to create their own ordinances, and police departments to enforce them. (Webster Groves was incorporated in 1897 after a murder, and “among the city’s first acts,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch writes, “was hiring a hard-nosed veteran of the St. Louis Police Department to clean out unsavory elements.”)

As early as the 1920s, the county was characterized by a sociologist as being made up of a “considerable number of small communities,” each “separate from the metropolitan city and… aloof from its neighbor.” At the same time, the Black population of St. Louis grew exponentially as part of the first Great Migration.

Over the course of the following decades, as Black residents began to move out of the North St. Louis neighborhoods they had largely been confined to into parts of North St. Louis County, local white leaders in the suburbs explicitly used municipal incorporation, zoning and police to ensure continued separation. Similarly, as white suburbs like Kirwood or Ferguson incorporated throughout the west and southern stretches of the county, their boundaries came into tension with small Black enclaves like Meacham Park and Kinloch.

At the same time, a long-extant but slow-emerging crisis in policing was revealing itself: an almost complete lack of standards that departments needed to follow, and criteria they needed to set, when seeking new officers.

While by no means the first of its kind, a 1977 scandal in the tiny city of Maplewood revealed the extent of this problem, especially when those controlling the municipalities hiring armed law enforcement officers were a handful of elected officials representing a few thousand residents.

A Post-Dispatch series early that year detailed how officers with the Maplewood force had conducted warrantless searches and beat and abused detainees, including with one-sided games of Russian roulette that had killed one arrestee.

Beyond the killing, which led to a manslaughter conviction and one-year prison sentence for that officer, the series exposed the lax hiring standards that Maplewood officers were subject to. Two officers were hired despite their own criminal backgrounds.

Lt. Raymond Heberer told the Post-Dispatch that he had repeatedly visited the house of a third officer, Lt. Joseph Sorbello, on complaints of abuse from his wife and children before he was hired onto the force. Sorbello denied the allegations and threatened to sue both Heberer and the newspaper reporters.

Maplewood police did not require any kind of psychological testing for new hires, unlike the St. Louis metropolitan and county police forces, the Post-Dispatch reported. The final step of the process — the only part required by state law — involved sending already-hired officers to the Greater St. Louis Police Academy. The academy’s director told reporters that he had to take everyone who had been hired by the area’s tiny municipal police forces.

“There are some departments that have excellent standards,” he said, advocating for statewide uniformity. “There are others that do not take care in hiring.”

Lt. Sorbello was charged in March 1977 with assault for a beating that had occurred three years earlier exposed in the Post-Dispatch series. But just a month later, a grand jury declined to indict him. In the following days, allegations would continue to emerge that Sorbello had lied under oath to a jury and forced a high school senior to play another one-sided game of Russian roulette after detaining him on suspicion of cannabis possession.

The police chief, who had supported Sorbello, was forced out by the city council and replaced by Heberer, who quickly fired Sorbello for refusing to submit to a lie detector test in an internal investigation.

Sorbello wanders to Bridgeton Terrace

Less than two years later, Sorbello returned to Post-Dispatch headlines for killing a man whom he alleged was attempting to steal his car by shooting him in the back. Though he was off-duty at the time, Sorbello was now serving as an officer for the tiny Bridgeton Terrace police, which patrolled some four blocks of around 400 residents before the municipality was largely destroyed for an expansion of Lambert-St. Louis International Airport in 1988.

He’d been hired by Chief John McGowan with full knowledge of his record. “He was never found guilty of anything,” the chief told the newspaper. “Our policy here is that if the man comes to us qualified, we take it from there and make our own judgment. Since he’s been here, he’s been a damn good cop.”

McGowan added the only thing preventing him from hiring Sorbello on full-time was budgetary constraints. Otherwise, he’d hire Sorbello “with no hesitation whatsoever.”

Over the coming weeks, a county grand jury investigation was opened into McGowan’s failure to ensure his officers had state-required training, and the Post-Dispatch reported that at least seven of the department’s 18 officers — including Sorbello — had previously been fired or were accused of significant misconduct while at previous departments.

McGowan, too, had himself resigned from the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department when he was suspended on accusations that he and another officer sexually assaulted a woman after arresting her. He was acquitted of sodomy charges before being hired by Bridgeton Terrace.

Law professor notices

Roger Goldman was a law professor at Saint Louis University who, while serving as the director of the ACLU of Eastern Missouri, had commented as an expert in the Post-Dispatch about the illegality of Sorbello’s warrantless searches in Maplewood.

How was it, Goldman wondered, that Bridgeton Terrace would have hired someone with Sorbello’s record, and how could he even still have been eligible to be certified as a police officer under Missouri law? Other professions — from medicine to law to cosmetology — took steps to remove bad actors. Why not the police, who had life and death control of people’s lives?

It turned out Missouri law did not even provide for officers to be automatically stripped of their state training certifications upon conviction of a felony. There was little chance that Sorbello, with his criminal acquittals, would ever be legally prevented from wearing a police uniform.

“At that point I got interested in this question that has haunted me ever since,” Goldman, who passed away in 2023, recalled in 2016. “How could we have allowed someone who did what he did in Maplewood to be hired by another department? And that set me on this 35 years of work to try to prevent the Sorbellos of the world from getting that second chance.”

Hancock amendment

In 1980, the year that part-time Bridgeton Terrace Officer Joseph Sorbello killed his would-be car thief, as he claimed, the tiny municipalities in the St. Louis metro became significantly more dependent on their police departments for revenue.

That same year, what became known as the Hancock Amendment was passed on a statewide ballot. It was intended to limit the size of government by requiring any property tax increases by a municipal government to be put to a vote of residents — rather than city councils or village boards — but it ended up instead encouraging the increased ratcheting up of fines and fees, especially after a subsequent Missouri Supreme Court decision found those types of revenue did not have to be put to the same vote.

All of a sudden, the inner ring suburb bedroom communities that were designed to rely on property tax revenue to sustain their existence had to look elsewhere. Though some were able to encourage commercial development, in many others, like Ferguson, white flight occurred as Black residents moved into the inner ring suburbs, and property values declined further.

“Just at the time” that Goldman and others were starting to take a hard look at the issues of police accountability that had been created by the rapid incorporation of the St. Louis suburbs, “those communities are undergoing this dramatic racial transition,” said Colin Gordon, a historian at the University of Iowa. “The impulse to sustain the color line is that much more powerful.”

Over the following decades, as Gordon shows in his 2019 book Citizen Brown: Race, Democracy, and Inequality in the St. Louis Suburbs, municipalities leaned more and more heavily on the fees and fines that they could freely levy on residents and travelers — some to the point of over 20 percent of their total local revenues.

Because the use of police to bring in revenue, rather than fight or prevent crime, is “aimed at enforcement of trivial violations of the municipal code,” Gordon writes, they rely on “a long litany of ‘failure to comply’ offenses that make it easy to manufacture an arrest out of virtually any police stop.… These laws are designed and enforced to extract revenue rather than to moderate or change behavior.”

The municipal fragmentation of North County also led municipalities to compete with each other to provide the best sales tax program to poach businesses from one postage stamp to another, according to anthropologist and historian Jodi Rios.

This, too, had a direct impact on the style of policing in each suburb. The cities that were able to win the sales tax battles could pass the benefits of the additional tax revenue onto their residents by relying less on fees and fines; in the other municipalities, sometimes right next door, an inverse effect happened.

“Not surprisingly, the majority of the cities that do not rely on sales tax because of a hollowing out of their tiny commercial districts are located in North St. Louis County,” Rios writes in Black Lives and Spatial Matters: Policing Blackness and Practicing Freedom in Suburban St. Louis. “The same cities that have lost the sales tax war are at the top of the list when it comes to per capita predatory policing practices.”

These marked shifts in policing begot the other phenomenon also sometimes referred to as the “municipal shuffle.”

In this shuffle, rather than mostly white police officers escaping accountability by exploiting loopholes to remain in positions of authority, the power was inverted.

Here, poor, mostly Black residents of the various municipalities or unincorporated areas of St. Louis County racked up the petty fines and fees that made up a significant portion of the municipal budget for whatever postage stamp they happened to have run through a stop sign in (if that).

They’re called into municipal courts, but often miss court dates. Even if they make their court dates, over time, the fees and fines increase, deferred or late payments result in warrants being issued, and a not insignificant amount of St. Louis County residents end up in modern-day debtors’ prisons.

St. Louis County’s history “primed” the region for these shuffles, Rios said in an interview. “It really paints a very extreme picture of things that are going on everywhere, but you really see it in that geography.”

Professors push new law

Roger Goldman began his fight by publishing an op-ed in the Post-Dispatch in 1984 proposing a decertification procedure in Missouri, and then began working with Steven Puro, a political scientist at SLU. The two found in a 1987 paper that 37 states had procedures for decertifying officers, but few used them. Missouri was one of the 13 outliers without any process at all.

Goldman’s research made its way to Clarence Harmon. Before he was the SLMPD’s first Black commissioner and the city’s second Black mayor, Harmon led the police department’s Internal Affairs Division from 1983 to 1988.

While in that position, “I was frequently called by potential hiring departments and asked to reveal the ‘real scoop’ behind the departure of an officer from our department,” he later wrote.

“Such a request for information would occur even when the officer was being criminally prosecuted, in which case I would be asked additionally to assess the probability of the officer being convicted. Such a question was an indication that, barring conviction, the department making this inquiry would be at least willing to hire this officer, and likely would do so.”

He and Goldman worked with Rep. Sheila Lumpe to propose the creation of Missouri’s POST commission, which passed the state legislature in 1988.

Goldman later recalled, “I’ll never forget Harmon testified… that in 90 percent of the cases where (city police) would leave under fire, they would be out working for a St. Louis County police department.”

The 58 small police departments in St. Louis County had an incentive to hire these St. Louis officers who quit under a cloud because the county departments could avoid paying for their training, hire immediately since they had their training certificate, and not have to pay a high salary since good departments would not hire officers with such a record.

Now, in theory, the newly-created state POST commission, installed within the Missouri Department of Public Safety, could strip the certification away from any who shouldn’t be working for any agency in Missouri, including for subjective reasons short of being convicted of a crime.

And, for the first time, there would now be central information tracking officers from department to tiny department.

In a 1997 study, Goldman and Puro praised the “broad” Missouri decertification system, comparing it favorably to others that only allowed POSTs to strip certifications after an officer had been convicted of a crime. But it also quickly became clear that, for however many problem officers the state was catching in its new net, many others were escaping accountability.

In 2000, an anonymous letter sent to St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Robert McCullough and later obtained by the Post-Dispatch exposed a scandal at the Webster Groves Police Department.

Officers from the department in the west suburbs had been having “hot tub parties” with teenage girls, where they supplied the girls with alcohol, the newspaper reported. Three officers were fired, and a fourth resigned.

Two of the officers, however, turned around and took jobs elsewhere in the St. Louis metro within weeks — one in Berkeley, the other in O’Fallon. The city failed to report any misconduct to POST about the officer who resigned, who took the job in O’Fallon.

The city’s failure to report, and the Post-Dispatch’s reporting of it, prompted POST to create new rules in 2001 requiring departments to notify them when officers leave under investigation, in addition to when they’re terminated.

POST director Chris Egbert said that he’d already tried to address the problem informally. “It is enough of a concern,” he told reporters, “that a number of years ago, we went around the state encouraging law enforcement agencies to send this very kind of information to us and not send their dirty laundry down the road to be cleaned.”

In response, Webster Groves Mayor Gerry Welch said she didn’t know why her department had failed to report the officer to POST — but, perhaps making Egbert, Goldman, and others’ point, insisted that “the important issue here is that the police officers accused of doing these things are not with the Webster Groves Police Department.”

Other communities, she said, “make their own choices” about what officers to hire.

“Without a state agency with the authority to collect information on past performance and prevent the officer from continuing in law enforcement by a procedure such as revocation,” Goldman and Puro wrote in a law review article about the case, “the movement of unfit officers among departments seems to be inevitable.”

“It is clearly unrealistic to expect local police departments and municipalities to solve [these] problems,” they continued, “because they are often not concerned about whether an unfit officer remains in law enforcement once that officer has left the force.”

Half a century after Great Divorce

Within half a century of the Great Divorce that split St. Louis city from county, and subsequently led to the proliferation of armed home rule municipalities, efforts to reunify began. Voters and legislators repeatedly rejected the proposals — in 1924, 1930, 1959, 1987 — and some pointed to concerns over local control over their police as a key reason.

In 1954, when the St. Louis County Council created the St. Louis County Police Department, the council had rejected the idea that the department would, by default, police the entire county. “Many of the municipalities would balk at relinquishing their police powers,” an official history of the department reads.

A 1988 study by the federal Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations asked local officials in smaller St. Louis County municipalities if they would be interested in disbanding their departments in favor of contracting with another city or the county police — as a handful of others already had.

Several of them “indicated that they may favor such a change, but were quick to add that citizens of their

communities would be reluctant to give up their local police,” the study’s authors wrote.

“Their assessments are consistent with the expressed sentiments of county residents reflected in a

poll conducted in 1982 by Market Opinion Research. In that poll, more than 80 percent of those

interviewed said that ‘direct local control’ of police was ‘very important’ to them.”

By 2011, different considerations ruled municipal decisions — in some places.

The system still existed, by all means. “There are a plethora of towns in North County — all of which share in common bad leadership, small departments, an emphasis on traffic enforcement, and poor pay,” an anonymous St. Louis County Police officer said in an interview with a SLU sociologist for a study released that year. “A lot of the officers… they’ll get fired from one and move to another.”

Still, circumstances had forced some local lawmakers to make difficult choices. That year in Jennings, the inner-ring North County suburb disbanded its police department and contracted with the county police after endemic police corruption, use of force, racial profiling, and a particularly bad incident in which a white cop shot at a moving car with an unarmed Black woman and her child in it.

“You’re dealing with white cops, and they don’t know how to address Black people,” Rodney Epps, a city councilmember, later said.

But all the same, disbanding the force did nothing to prevent those same white officers from moving on to police other mostly Black St. Louis County suburbs — municipalities that could “make their own choices,” in the words of former Webster Groves Mayor Gerry Welch.

One of them was Darren Wilson, who, on August 9, 2014, killed Michael Brown while serving as an officer with the neighboring Ferguson Police Department.

Wilson had been attempting to stop Brown, he claimed, for one of the many petty offenses that cities like Ferguson built their municipal budgets around: walking in the street.

Despite Goldman and Harmon’s efforts decades prior, POST was in no position to have addressed or prevented Wilson from ever ending up in the position where he had the ability to kill Brown and get away with it.

Decertification help in Ferguson

Even if the unconstitutional style of policing in Jennings had been fully exposed, especially upon the department’s disbanding, POST operates largely on reports from agencies about their own officers’ misconduct. Jennings never reported any discipline of Wilson; it’s possible he committed no misconduct there, but it’s also possible that it was never reported to the department or never investigated fully.

Beyond that, POST was historically underfunded. The Post-Dispatch reported in 2003 that it relied on just one investigator, who had 90 cases at any given time. Departments got out from under the reporting requirements put into place after the Webster Groves scandal by simply deciding to not complete internal investigations upon an officer’s separation, the newspaper found.

A state audit conducted two years later found the system, often described as one of the strongest in the country on paper, all but in shambles, failing to maintain or ensure that departments submit accurate records.

“POST officials are not effectively using the information contained in their officer database to manage the POST program,” the audit found, recommending that the agency analyze the employment history data for trends in individual officers or departments. “The POST officer database is an important tool for the POST program and should be used effectively to improve program performance.”

In 2013, the chief executives of both St. Louis city and county, along with other local power brokers, launched the latest government consolidation initiative, which they termed Better Together. Less than a year later, Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown, and the Better Together leaders hired the Police Executive Research Forum to look into creating a “regional approach” to policing.

PERF’s report, released in April 2015, made clear that, again, little had changed at POST.

“The term ‘muni shuffle’ is ubiquitous in the St. Louis region,” the report’s authors wrote. “Nearly every constituency that we met with used the phrase at least once.… The fact that the muni shuffle was the subject of a St. Louis Post-Dispatch investigative series back in 2003, yet remains a common occurrence today, is cause for concern.”

The report identified one of the “primary enablers” of the shuffle as “a severely underfunded and understaffed monitoring and investigative system operated by the state’s POST program.” PERF found that POST’s investigative team had doubled in size; now, two investigators handled the 100 or more active complaints at any given time.

As a result, the group found, “the system still relies on the reporting of local law enforcement executives.”

The strong, broad system of oversight and decertification pushed for by Goldman, Harmon, Rep. Lumpe, and others — and potentially achieved on paper — had clearly not been realized on the ground in Missouri.

Extreme secrecy

The 2005 audit also noted that extreme secrecy had also somehow been built into the Show-Me State’s system. “State law prevents POST program officials from revealing employment history to prospective law enforcement agency employers,” auditors noted.

Both the auditor’s office and POST interpreted a state law passed in 2001 as blocking the agency from releasing employment history information to either the public or other law enforcement agencies.

The law states that “the name, licensure status, and commissioning or employing law enforcement agency, if any, of applicants and licensees pursuant to this chapter shall be an open record. All other records… pertaining to any applicant or licensee shall be confidential.”

The audit noted several cases of wandering officers that POST could have notified agencies of, if it thought it was able to. “We agree that [the law] should be changed to permit this office to inform law enforcement agencies of a prospective employee’s former employers,” POST wrote in its response. It couldn’t provide a timeline to implement this change, as “legislative proposals must be presented to the Governor.”

Regardless of if changes ever were presented to the governor, the law remained unchanged through the reforms proposed and passed after Michael Brown’s killing, after George Floyd’s murder, and on to today. The same law is now cited by the Missouri Department of Public Safety, on behalf of POST, to block the release of the state’s employment history data to reveal the still-extant wandering officers.

“It’s quite clear and it’s a statutory exception to the Missouri Sunshine Law. We have provided all the information that is open under state law,” Mike O’Connell, the director of communications for DPS wrote in response to a 2023 records request.

He also refused to release the former employing agency of officers that POST had decertified. In response to a follow-up, he wrote, “You correctly state that ‘Decertified officers had a commissioning agency.’ That is no longer the case. DPS applies the statute which requires closure.”

It’s unlikely that the current political or legal climate in Missouri would prove particularly friendly to a legal appeal of DPS’s denial.

Records about police misconduct previously deemed public by Missouri courts were barred entirely from public access by the legislature in 2021, in the same law that also required local agencies to indemnify their officers from civil lawsuits unless they’re convicted of a crime. The legislature has also moved to block public access from myriad court records previously available, including the names of arresting officers in criminal cases. Even basic reforms to track police misconduct and use of force without revealing officers’ names have failed.

Reforms fall short

The Better Together initiative, ultimately put forward in 2019 after years of study, proposed consolidating local police as a central plank of its efforts. Rather than nearly 60 departments, mostly concentrated in North County, there would just be one, also combined with the St. Louis County and Metropolitan Police Departments.

The group’s report noted that some small steps towards consolidation had begun to occur. Jennings, for one, had disbanded its department and contracted with the county police in 2011.

Pushback to the Better Together recommendations, including from many police groups, was immediate, and within a few months, the plan to list the initiative on a statewide ballot was withdrawn.

A year later, after the murder of George Floyd, the Post-Dispatch again revealed examples from the depths of the “wandering officer” crisis, and again, POST responded with incremental reforms. The North County city of St. Ann, with one of the only elected police chiefs in the region, attracted scores of officers with histories of misconduct in other departments.

For one, Ellis Brown, one of the SLMPD officers who killed 25-year-old Kajieme Powell in 2014 days after Michael Brown’s killing, landed in St. Ann after a separate case in which a car he and his partner were tailing crashed and lit on fire — which they failed to report. He was eventually promoted to lead St. Ann’s department’s detectives bureau.

In December 2020, the POST Commission passed recommendations for some modest administrative reforms — most significantly proposing that would-be officers should sign a waiver allowing their new agency to obtain their previous employment file from POST, which finally comprehensively addressed the internal law enforcement transparency issue identified in the 2005 audit. It also, in turn, required police departments to actually obtain that file and sign a form attesting that they reviewed it.

The recommendations also called for departments to be required to conduct background investigations, though they were silent on how extensive those should be.

Jefferson County Sheriff Dave Marshak, a POST commissioner, made clear at the time that these were just an incremental step forward, the Post-Dispatch reported. POST still employed only two investigators to add reports to that state employment file that departments were now required to access. At the time of the Post-Dispatch story, they had a combined caseload of 180.

It’s unclear if the recommendations were ever implemented, though a bill that provided departments with immunity for releasing disciplinary records to other agencies did pass in 2021. Still, officers in Missouri continue to wander.

In the following years, there have been a few other minor attempts at tackling the larger issue of the officer shuffle — a successful push to allow POST to decertify for off-duty actions, a proposal from a Kansas City-area Republican lawmaker to force departments of a certain size to consolidate or contract out that went nowhere.

But the amount of departments in St. Louis County has decreased, slightly. The most prevalent impetus for the reduction has been the same as what prompted them to rely on predatory policing in the first place: money.

In 2015, the state legislature placed limits on the amount of revenue that municipalities could bring in through their police. Courts have bounced back and forth about whether these limits were legal, but the uncertainty about whether they could proceed policing as they had prompted some local communities to reconsider.

Since Jennings contracted with the St. Louis County Police Department, several other municipalities have disbanded or merged their police departments. Sometimes, that happens haphazardly. In March 2024, after financial hardships and a failed vote to contract with Hillsdale, the Velda City Police Department’s entire three-person force resigned, resulting in the Pagedale police taking over for the 2,000 residents of Velda City and Flordell Hills, which the three officers also patrolled.

A month later, nearby Bel-Nor announced that its department would be disbanding, too, with the Board of Aldermen citing budgetary issues. They contracted with St. John, prompting the chief in neighboring Normandy to question why his department wasn’t allowed to bid for the contract.

In June, Flordell Hills left the Pagedale contract to join what’s been the most purposeful consolidation effort: the North County Police Cooperative (NCPC).

In 2015, the Vinita Park Police Department took over services for Wellston and renamed itself as the NCPC. “This is not going to be Vinita Park coming in and taking over. It can’t happen that way,” said Tim Swope, the Vinita Park chief who would be helming the new agency. “This is all of us joining together and having some skin in the game.”

Since then, it’s taken over for the departments in Pine Lawn, Hanley Hills, Beverly Hills, and Uplands Park, and as well as the county police’s contract with Dellwood.

In 2016, Swope discussed the new, stricter hiring standards that he had set. “Some people were left out,” he told St. Louis Public Radio. “That’s not good for them, but it’s good for all the communities.”

Left unsaid is what happened to those who were left out, or later cast out by Swope — let alone those who make it through those higher standards and still commit misconduct. Though it’s not known why Samuel Davis, the former NCPC officer who is now under state and federal charges for his actions with Northwoods, left the cooperative, serious questions have been raised about the NCPC’s hiring process in a different case.

Marcellis Blackwell was an NCPC officer who joined “to be a part of the change,” he told a reporter when he graduated from the academy.

Within a year, he was under state and federal charges for sexually assaulting male detainees. An investigation by Riverfront Times found that Blackwell, who had legally changed his name, had been sued for defrauding an Illinois insurance company, and had his wages garnished in Indiana for failing to appear in court.

“To find out that he was hired on by any police force is complete negligence,” his insurance fraud victim told the RFT. “Anyone and everyone who knows anything about people should have just Googled him.”

The haphazard disbandings and consolidations present another issue to ArchCity Defenders, communications director Z Gorley said, because POST’s refusal to release anything except snapshot-in-time data means that it’s all but impossible to see who the officers being passed around in that process are.

“It’s especially problematic,” they said, “because there’s just no public record of these big changes that are happening institutionally, within local governments, and that is what a lot of taxpayer money is spent on.”

Push for more consolidation

Even with the reforms passed in recent years, and the continuing efforts of groups like ArchCity Defenders to push the municipal court system to consolidate, North County municipalities are still heavily reliant on predatory policing to sustain themselves — and the “officer shuffle” continued unabated, and unmonitored.

There’s an unfortunate irony, given that the depth of the problems in St. Louis County have prompted reforms elsewhere — reforms that North County residents still largely don’t feel the privileges of.

Getting the bill that created Missouri’s POST Commission through the legislature in 1988 was “my proudest achievement in police decertification,” Roger Goldman later wrote. He noted that he had directly assisted efforts in a handful of other states, but in some of those, the laws that were enacted were weaker than Missouri’s because “leadership in those efforts need to come from residents on the ground in the state, not an outsider.”

His ideas and scholarship, however, have helped to push state-level police oversight across the country.

Though its final report didn’t go as far as his recommendations, he sat on President Barack Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. At least 17 states created decertification provisions in the years after his successful public advocacy in Missouri. One of his articles, published in 2012, outlines what he views as the necessities for a “strong decertification law.” In recent years, it has been cited by advocacy or reform groups to push for stronger oversight in Illinois, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C.

Notably, two of those jurisdictions make public what Missouri can’t, or won’t: police employment history.

The Illinois Law Enforcement Training and Standards Board published a lookup tool for officer data in recent years, which allowed for the quick reporting that Sean Grayson, the former deputy sheriff charged with murdering Sonya Massey, had worked for six departments in four years. Massachusetts POST is releasing data on certifications and misconduct as its system is being created, after years of there being no police certification system in the state at all. (D.C. still has no decertification function, but publishes current and historic district-wide salary data.)

Wandering officers are — because decertification systems are ultimately still so weak — endemic in American policing. Due to actual or perceived hiring shortages in many departments across the country, wandering officers may now have an increased opportunity to continue wandering as they never have before. Ultimately, it never was a problem unique to St. Louis or Missouri.

But it was a problem so acute there that it led a reformer to spend the rest of his professional life pushing for, ultimately, officers to stop being allowed to wander. And still, almost monthly reporting in the St. Louis metro shows that they continue to wander.

What is different in Missouri — especially when compared with its neighbors Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Nebraska, and Tennessee — is that the state entity responsible not only refuses to study or quantify the problem, but also refuses to allow the public or press to do so, either.

Rather than impose additional oversight and scrutiny on policing after Michael Brown’s killing, state policy has gone the other direction, said J.P. Clubb, a former assistant attorney general who works on Sunshine Law issues.

“Missouri has granted broad immunity to police officers for their criminal and tortious behavior, while at the same time passing laws that restrict the public’s access to public records documenting police officers criminal behavior,” he wrote in an email.

“These laws only serve to help bad cops transfer from department to department throughout Missouri and Missouri citizens deserve to know who is policing their neighborhoods.”

Ultimately, without larger national reform, there is little that will prevent the movement of officers between departments, and ultimately, between states.

When Samuel Davis, the former Northwoods police officer who had beaten and left Garmon outside of a manufacturing plant, was brought in on state assault and kidnapping charges, he had been applying to a new job in policing — in North Carolina. He was taken into custody by the Fayetteville Police Department there after recruiters reviewing his application to that department saw there was a warrant out for his arrest. Had criminal charges not been brought by state and federal prosecutors, he could very well be working as a police officer in another state.

Sam Stecklow is a journalist for the Invisible Institute. He works on the Civic Police Data Project, investigations throughout the organization, and II’s initiative to expand its police data and journalism work throughout Illinois. Sam has been lead FOIA journalist since 2018. William H. Freivogel is publisher of GJR. This story first appeared in the summer 2024 print issue of Gateway Journalism Review.