Carlo Rotella knew when he set out to write a journalistic memoir that he’d have to be conscious of the different roles he’d play as investigative reporter, writer and storyteller.

Not only does his book, The World is Coming to an End, focus on the greater divide between economic and social classes all from the perspective of South Shore residents, a small neighborhood on the south side of Chicago–but it also represents how journalistic training can spread far beyond news clips and headlines.

For Rotella, an English professor at Boston College who regularly contributes to the New York Times magazine, the key is in knowing the boundaries of both writing a memoir and writing a piece of journalism while emphasizing that line whenever it is unclear.

“When I was moving in those different settings or modes, I had to play by the rules of that mode,” said Rotella who grew up in the South Shore neighborhood and is co-editor and founder of the University of Chicago Press’s “Chicago Visions and Revisions” book series. “But my overarching rule is the rule of the essay, and the rule of the essay says that you can put very unlike things together as long as they’ve got a singular purpose.”

The purpose? Showing how our neighborhoods live inside all of us, which is particularly important for communities like South Shore that are often lumped together in a media-driven narrative that defines the South or West sides of Chicago as violent and dangerous.

This idea, often emphasized by politicians and the Trump Administration, creates a false divide between community members of different socio-economic levels. However, neighborhoods like South Shore do not reflect this.

“There are things that we all agree on and come together, and it doesn’t matter what we disagree about,” said Val Free of the Neighborhood Network Alliance. “Most people who write about South Shore from the outside don’t understand that.”

Free continued saying that the predominantly black community is never publicly divided; if they are not in agreement then they remain neutral, which does not necessarily make for enticing news. In this sphere, Rotella’s book builds a bridge between the idea of a Chicago neighborhood and the reality of its residents.

While exploring the idea of the meaning of neighborhoods, Rotella, a former op-ed columnist for the Boston Globe, also worked to flush out the differences between neighbors that might work to divide or unite them, and South Shore was the prime backdrop to highlight these themes.

“There are very few communities in Chicago where they are, say, integrated by class,” said Bradford Hunt, vice president for research and academic programs at the Newberry Library, when reflecting on how older neighborhoods such as South Shore are unique because of their range of housing and furthermore diversity of residents’ socio-economic levels. “I would probably put South Shore in this group as it has this huge range from the Highlands to those apartment buildings.”

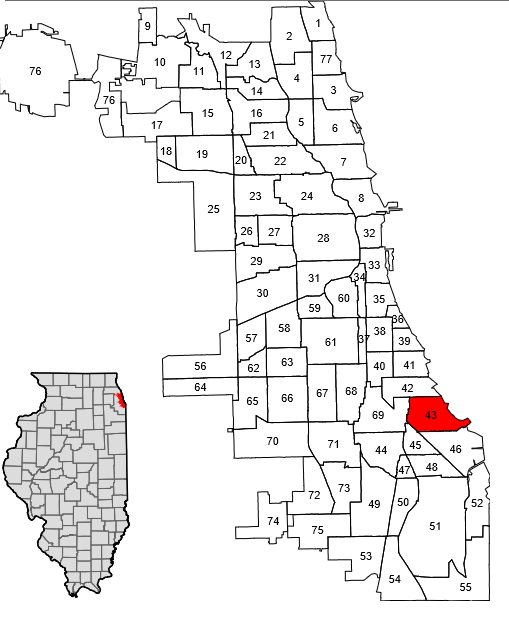

Many of Chicago’s neighborhoods have been historically divided by racial and class lines, while South Shore has tended to be more of a mix, Hunt said. The neighborhood has been home to European immigrants in the late 19th century and then African Americans during the Great Migration, creating a collision of identities that is still seen amongst its residents. South Shore is located along the lakefront just south of Jackson Park, where the Barack Obama Presidential Center is planned.

Pulling in examples from his own life in South Shore and experiences of community members, Rotella’s mix of reporting and personal narrative create a complex image of South Shore defined by its mix of race and class.

Yet, this bridge was not built in a day. Rotella only felt prepared to take on the 10-year project that would become his book, published by the University of Chicago Press in 2019, after having years in journalism under his belt and a stable day job as a professor.

Despite writing about personal experiences and changes that he witnessed in the South Shore community, Rotella said that his work in journalism aided him in interviewing other community members and incorporating their perspectives.

“One of the techniques that I used in assembling the materials of this essay was journalism. But I would not… claim that all of it, everything that I did in the book, meets the standards of objective journalism because it’s not true.”

Because his book was not simply a memoir or simply a piece of investigative journalism, Rotella said it was important to make the line between objectivity and subjectivity very clear and say, “Okay now I am stepping over on the other side. Now I’m going to tell you about this fight I got in with Alfred… when I was six years old. This is not news, and I’m not pretending that it is news.”

But Rotella contributes much of his ability to write and be edited to his journalism training. Despite never studying journalism in college, Rotella learned how to report by being edited, a process he called “reverse engineering.”

“I learned by doing basically. I knew that I wanted to write for magazines and do journalism in one form or another—that is magazine or book length.”

He first started working at DoubleTake, which Rotella poetically described as a photography magazine where “the pictures don’t illustrate the writing and the writing doesn’t describe the pictures.” There his passion for storytelling took hold.

“I wanted to tell stories of people living the consequences of history or some bigger structural change, or some kind of big-picture thing that was happening to them,” Rotella said. “There are many ways to do that; you can do that with footnotes and call it scholarship, you can do it in a magazine and call it journalism, but to me it’s all one thing that is showing how people live the consequences of bigger changes, bigger transformations of the world.”

He found quickly that there were many ways to tell people’s stories, particularly in entry-level positions. It was clear to Rotella that you do not need to be a world-class journalist to write impactful articles.

As for exploring how the objective nature a journalist must inhabit and the subjective nature of being a human being, Rotella is still working on how the two collide within the industry.

In one sense, Rotella stated that the personal connections reporters have to their stories will always be present in their writing. “There’s a way, not only in writing the story but in reporting the story and even in pitching the story to your editor where you do use your authority as a person who was there, who knows that neighborhood, who knows that kind of neighborhood to say ‘I have a take here and this is my take’.”

This authority and experience on the part of the journalist shows in everything from the people interviewed to the choice of an adjective.

“Through who their sources are and what they know, and their confidence that they can see beneath the surface of what they’re seeing down to its essence and all that is often connected to their experience.”

In another sense, Rotella addresses the caveat that not every piece of journalism should be subjective in its creation and execution. His book, for example, is not what Rotella would call “only a work of journalism”.

While subjectivity and a journalist’s experience can create a more in-depth coverage of a story, Rotella explains that the aspects of his book that reflect his years in journalism are present in his interviews of other community members.

Contrary to his journalistic practices, writing a memoir required Rotella to dive deeper into his past and analyze every experience he had in his neighborhood in order to see the changes and trends of South Shore. Part of this was identifying and confronting the ways that his actions reflected or rejected his social and economic privileges. In a way, this became the foundation for the book.

“In a place like South Shore you are always, always reminded about the basic fact of life that those who have more want to hang on to it and those who have less want more. You can’t walk down a street in South Shore without being reminded of that.”

Despite adding to the conversation of objectivity versus subjectivity that many journalists are debating, Rotella’s hopes for the book is simple: to contribute to a long history of written works focused on Chicago’s neighborhoods.

“I think the literature of people’s relationship to place is a great and a deep literature, and in no place is it deeper than in Chicago,” Rotella said. “There is a Chicago tradition of making literature out of your neighborhood, and if the book is a contribution to that tradition then I’m happy.”

Marin Scott is a correspondent for GJR based in Chicago, where she is a student at DePaul University and vice president of the student SPJ chapter. You can connect with her on LinkedIn.