Missouri, Arkansas, Iowa, Tennessee, Wyoming, Texas and Florida remove hundreds of books despite the First Amendment

NIXA, Mo. – When Glennis Woosley entered Nixa High School, she found herself at the center of a book banning controversy that attracted national and international attention. Woosley joined Nixa’s Students Against Book Restrictions SABR, attending a June, 2023 school board meeting to resist a campaign by adults to remove books from the library shelves.

The Nixa students found themselves talking to reporters from around the world who were reporting on the controversy in this small town in Christian County in southwest Missouri. Reporters from The New Yorker, the Christian Science Monitor, the Washington Post, the Jerusalem Post and local Springfield media interviewed the students.

“I was like ‘Oh my gosh, this is actually happening in the world and it is happening to us,’ Woosley said in one media interview.

“We are in high school,” she said. “We can put context to those books because we have been taught how to do that by those people around us who are acting like we can’t.”

Thomasina Brown, then a senior and a member of SABR, told the Christian Science Monitor, “We felt that we weren’t being heard.”

Nixa had become a focus of national debate when the Missouri Legislature passed SB 775 making it a crime to provide “explicit sexual material to a student.”

States in the Midwest and South have been passing similar broad laws that apply the same sexual material standard to high school students as kindergarteners. That causes high school students to rebel and civil liberties lawyers to go to court. (Eight cases to watch)

Some of the most important of those school cases are ending up in the federal appeals court in St. Louis – the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Broad book ban laws from Arkansas, Iowa and Missouri will be governed by that court’s decisions.

Just last week, lawyers challenging Arkansas’ law told the court in a written brief that the First Amendment means, in the words of attorney Rebecca Hughes Parker, that “A state cannot criminalize making books available to a 17-year-old because they might be obscene for the youngest minors….it cannot impede access to books because it dislikes their viewpoint.”

The challenge by the ACLU and the Missouri Association of School Librarians to Missouri’s SB 775 law – Missouri Association of School Librarians v. Jean Peters Baker – is meanwhile languishing in Jackson County Circuit Court. Whatever the 8th Circuit decides in the Arkansas case will govern the decision in the Missouri’s case.

‘Normalization of book banning’

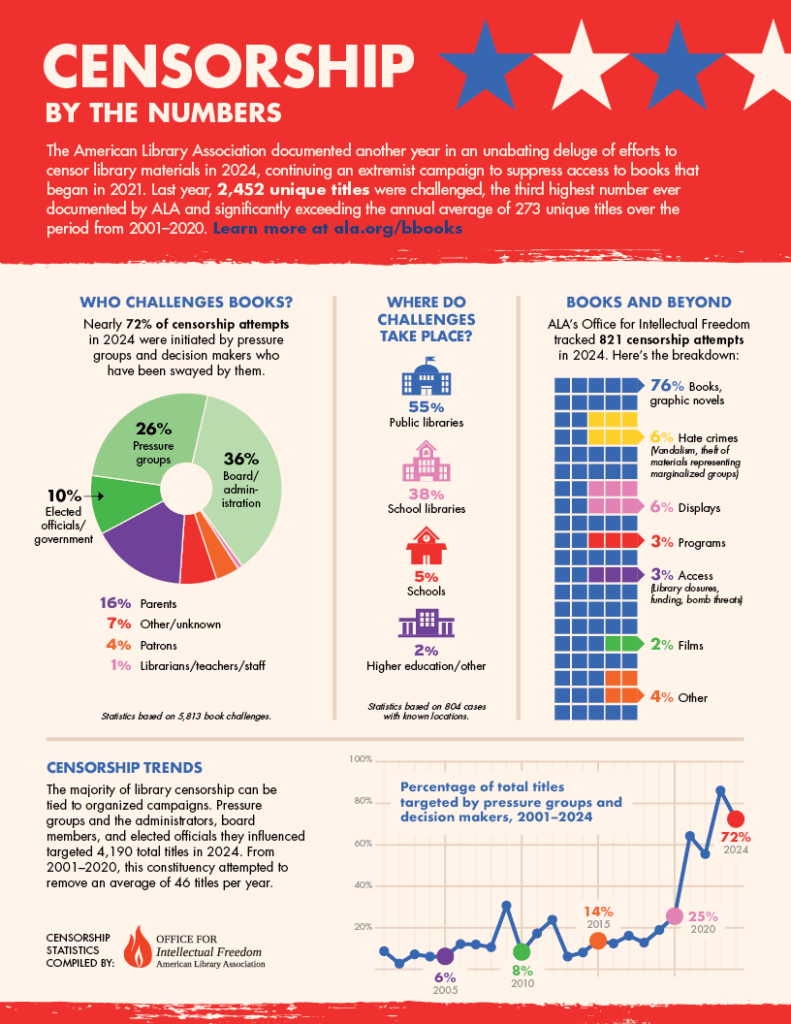

PEN America, which tracks book bans nationwide, concluded this year that the nation has undergone a “normalization of book banning.”

It wrote: “Never before in the life of any living American have so many books been systematically removed from school libraries across the country. Never before have so many states passed laws or regulations to facilitate the banning of books, including bans on specific titles statewide. Never before have so many politicians sought to bully school leaders into censoring according to their ideological preferences, even threatening public funding to exact compliance. Never before has access to so many stories been stolen from so many children.”

PEN America found that during the 2024-2025 school year, 6,870 instances of book bans across 23 states and 87 public school districts.

Altogether, since the book bans became common in 2021, there have been 22,810 cases of book bans across 45 states and 451 public school districts.

A 2024 law in Tennessee led to that state shooting up to third place in the number of banned books – 1622, right after Texas with 1781 and Florida with 2304, PEN found.

The Tennessee state legislature decided last year to amend the “Age-Appropriate Materials Act of 2022” to specify that any materials that “in whole or in part” contain any “nudity, or descriptions or depictions of sexual excitement, sexual conduct…’ are inappropriate for students of all ages.

The books removed include classics – Magic Tree House author Mary Pope Osborne, children’s poet Shel Silverstein and Calvin and Hobbes cartoonist Bill Watterson. They joined previous exclusions of Judy Blume, Sarah J. Maas, Eric Carle and Kurt Vonnegut.

Osborne’s Magic Tree House series sends siblings, Jack and Annie, time traveling to historical destinations for adventures. A book she wrote with her sister, Natalie Pope Broyce, “Ancient Greece and the Olympics, a Magic Tree House Fact Tracker,” meant to be a learning companion to “Magic Tree House #16: Hour of the Olympics,” was one of 574 books removed from Monroe County school libraries. The book’s cover features a nude Greek statue of an Olympian throwing a discus.

Most of the lawsuits against state book banning laws target the overly general and vague language that calls for removal of books that are sexually suggestive. Also, almost any reference to LGBTQ activities is a rationale for removal.

Woosley, the Nixa student, put it this way in a Nixa Eagles’ podcast: “A lot of times, people claim that these books are sexually explicit or too inappropriate for children. But we’ve also noticed that a lot of these books tend to have queer characters and people of color. And we’ve connected the pieces a little bit there. But overall, it’s just – book banners claim is that they’re too sexually explicit for us, even though we’re high schoolers and we can put context to these books…I personally think that it’s unfair to leave students out of what they’re reading and what they’re allowed to read.”

On May 12, 2022 hundreds of Nixa residents crammed into the community room and in an overflow room to call for removal of objectionable books. Before the meeting, students from the high school presented the board with a petition signed by 345 students opposing removal of the books.

“Some of the speakers called the school librarians pedophiles and groomers who should be arrested and put on a national sex-offenders registry,” The New Yorker reported.

A year later, at a June 20, 2023 meeting, the board decided not to ban Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Holocaust memoir “Maus,” in a win for students. But after a long meeting where some students felt intimidated by shouts and comments from adults, the board banned “The Handmaid’s Tale” and “Blankets.” The board also banned the young adult novel “Unpregnant,” which is about pregnancy and abortion, and the children’s book “Something Happened in Our Town,” which is about police brutality.

Woosley explained during an interview after the meeting: “The conversation on “Unpregnant” was long. It’s the story of a girl, coming from a Christian conservative family, finding out that she is pregnant, and she’s a teenager. And so she and her friend try to get an abortion for her, and it takes place in Missouri in a very similar town as Nixa. So that’s why this book is so big and important around here. And she has to go to New Mexico to get an abortion. It’s a comedic book. And a lot of school board members were saying that they were taking the subject of abortion and making it light-hearted and normalized in ways they didn’t agree with. That was the main thing they talked about. Some of them also said that it was encouraging abortion, and they didn’t want students to be encouraged to have abortions.”

Are book bans state speech?

A key question for the courts is whether a school board decision to ban books is protected as government speech. The argument goes like this: Curating library books amounts to “government speech” akin to raising a monument in a town square.” If it is, then the students wouldn’t have a First Amendment right to read. The government’s speech would trump the student’s right to read and obtain information.

Seventeen state attorneys general have argued that when the government creates a library, that is government speech and the end of the issue.

That view received support from the conservative 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals recently in a case from Texas. A majority of the court refused to recognize the First Amendment right to receive information and to challenge a library’s removal of books as abridging that right. A minority of seven judges of the full court said “a public library’s collection decisions are government speech”.

The 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis has so far contradicted that view. Last year, in an Iowa book case, it said “public school libraries do not share the characteristics of monuments in a park. . . . [I]t is doubtful that the public would view the placement and removal of books in public school libraries as the government speaking.

“Take routine examples of historic tomes on political science. A well-appointed school library could include copies of Plato’s The Republic, Machiavelli’s The Prince, Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, Karl Marx and Freidrich Engels’ Das Kapital, Adolph Hitler’s Mein Kampf, and Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America. …if placing these books on the shelf of public school libraries constitutes government speech, the State ‘is babbling prodigiously and incoherently.’”

Another important legal issue in the book ban cases is whether the 1982 precedent of Island Trees School District v. Pico is still good law.

The Island Trees school board had removed books from the junior high and senior high libraries that it thought were “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic, and just plain filthy.”

The Supreme Court found that school officials cannot remove books solely because they disagree with the views expressed in the books but that they can make content-based removal decisions based on legitimate pedagogical concerns such as pornographic or sexual content, vulgar or offensive language, gross factual inaccuracies, and educational unsuitability for certain grade levels.

School boards “rightly possess significant discretion to determine the content of their school libraries,” the court wrote, “But that discretion may not be exercised in a narrowly partisan or political manner. If a Democratic school board, motivated by party affiliation, ordered the removal of all books written by or in favor of Republicans, few would doubt that the order violated the constitutional rights of the students denied access to those books. The same conclusion would surely apply if an all-white school board, motivated by racial animus, decided to remove all books authored by blacks or advocating racial equality and integration. Our Constitution does not permit the official suppression of ideas.”

To the contrary, Pico recognized a constitutional right to receive information, without which the right of free speech would be meaningless.

“The dissemination of ideas can accomplish nothing if otherwise willing addressees are not free to receive and consider them. It would be a barren marketplace of ideas that had only sellers, and no buyers,” it reiterated.

Pico generally supports those challenging book bans, but is a weak precedent because there were not five votes for a single legal rationale. That said, seven of the justice agreed books couldn’t be removed for ideological reasons.

Daniel Novack, whose Penguin Random House firm has led the effort against book bans, recently told a gathering of lawyers that 80 percent of Americans support allowing their libraries to curate their collection. And he noted it was a pervasive issue across the country, which has even more libraries than McDonald’s.

Novack wondered if the backlash to Disney taking Jimmy Kimmel off the air last month might spur the anti-censorship sentiment. He added, It’s time to step up.”

As for Woosley, last school year she organized an observance of banned book week. And she’s planning a career as a journalist. This year she wrote, “While the 24-hour news cycle can invoke fear and paranoia, a world without news is not all rainbows and sunshine. Instead, we would live in ignorance. The knowledge of events happening on the other side of the world or even in your local community is a privilege.”

“The speech we hate series” is funded by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. The first three stories in the continuing series are here, here and here.