When the earth unspools before the sun on Nov. 1, its cargo will include a human population of some 8.2 billion. Of that total, the number able to claim residence for 100 years or more will be a mere 722,000 – .0088 percent.

Roughly 1,300 of that group will be Missourians – of whom only about 200 will be men.

One lives in University City and will be celebrating his centenary that very day. A cane notwithstanding, he will still be walking with an erect carriage. His daily routine will still feature several hours reading The New York Times and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (hard copies). And he will still start most days by writing an email assuring his daughters that all is well. Daughters, after all, must be humored.

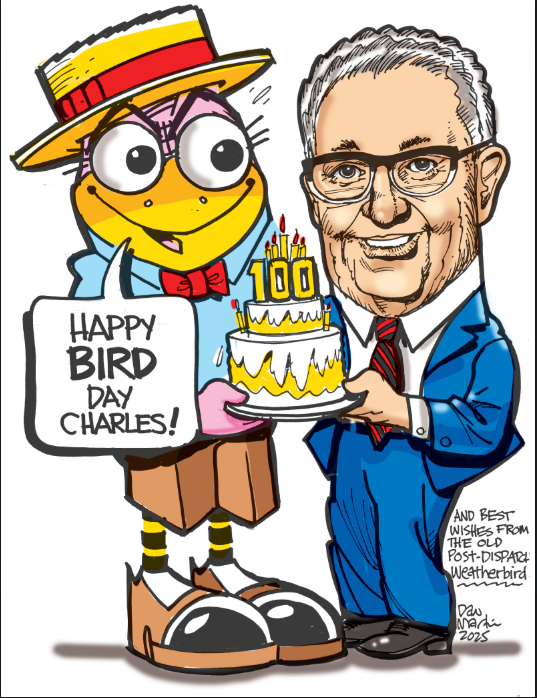

This man is Charles L. Klotzer. From an actuarial standpoint, he is one in 40,000. From any other perspective, he is one in millions.

His life story would challenge fiction writers, let alone statisticians: an Act I in Berlin, Germany, where three nights before his scheduled Bar Mitzvah his synagogue was destroyed in the Kristallnacht rampage; an Act II in Shanghai, China, where he spent nine years in conditions many refugees there found unbearable (typhoons, intense heat, freezing cold, malaria, hunger); and an Act III – starting in 1948 – in St. Louis, where he achieved local and even a degree of national renown as the founder of the St. Louis Journalism Review (SLJR), now the Gateway Journalism Review (GJR).

Klotzer will be publicly honored Sunday, Nov. 2, at the GJR’s First Amendment Celebration, at the Frontenac Hilton Hotel. The annual benefit. which previously has featured such eminences as Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein and Judy Woodruff, will be headlined this year by Marty Baron, the former top editor of both the Washington Post and the Boston Globe.

At least one ingredient in the GJR’s ability to lure heavyweights like Baron has been Klotzer himself. He is widely respected not only for having founded the SJR in 1970 with help from his wife, the late Rose Klotzer, but for having personally subsidized it for decades despite modest personal circumstances.

Written by volunteers from the local media and edited by Klotzer himself, the SLJR revealed issue after issue how journalism was not only a calling but a business. It also kept local journalists on their toes by exposing shortcomings in the way news was covered. It pulled no punches and won national as well as local journalism awards.

Klotzer ran it until 1995; then gave it to Webster University; then took it back 10 years later when the university decided it would not subsidize its print edition any longer and would instead take it online – a plan Klotzer abhorred; then held onto it until finding a new sponsor in Southern Illinois University Carbondale (SIUC) in 2010. Editorial leadership is now provided by William Freivogel, a veteran St. Louis journalist and professor in the Charlotte Thompson Suhler School of Journalism and Advertising at SIUC, and Jackie Spinner, another veteran journalist and a professor at Columbia College Chicago. Klotzer continues as an adviser.

The GJR is now the last print journalism review in the country. (It publishes online too.) Immodest as it may be to say so in these pages, it is a mouse that roars. Its circulation, print and online, is microscopic. But its coverage of such issues as racism, politics, the courts and police accountability has won it a footlocker’s worth of national reporting awards, including at least one in each of the last five years.

Given his biography and legacy, the opportunity to honor Klotzer on his centennial is of course obvious. But the reasons for celebration go much deeper. Conversations with those closest to him show that the man is simply revered.

In part this is because the unselfish commitment he has shown in his journalistic endeavors is typical of his approach to life. “One of the great lessons that I think I learned growing up with him is, you do what’s right regardless of the outcome,” said Miriam Rushfinn, of Charlottesville, Va., his eldest of his three adult children. The others are Ruth Baruch, or Chicago, and Daniel, of St. Louis. Klotzer also has four grandchildren

Publishing the SJR on his own nickel is only a part of the story. Klotzer and his wife Rose resisted the white flight that seized University City in the late 1960s and unlike many other white parents, kept their three children in the public schools. After Rose entered a long decline that ended in her death in 2019, Klotzer initially served as her “nonstop caretaker” at home, Rushfinn recalled. Then, after she had to be institutionalized, Klotzer “was there all day long every day. He just took his computer, he took his papers, and he was there with her every day.”

In the broader world beyond the family, this strong moral compass typically points left. For example:

- Having arrived from Shanghai in San Francisco, he chose St. Louis as the family’s destination in part because he thought one of the other options presented – in the South — would be too racist. (He also thought the Mississippi would be lined with restaurants, like the Seine or Danube.)

- Only a few years after arriving in St. Louis, he protested the exclusion of Blacks from the swimming pool at the YMHA (Young Men’s Hebrew Association).

- His first publication, FOCUS/Midwest, a magazine he and Rose published from 1962 to 1982, devoted significant space to social justice issues and carried columns by such noted liberals as Minnesota Sen. Hubert Humprey and former Post-Dispatch editorial page editor Irving Dillard. (It also featured poetry selected by no less an authority than Washington University’s Donald Finkel.)

- In 1988 he headed the presidential campaign in Missouri of Illinois Sen. Paul Simon, another strong liberal (and the person who, remarkably enough, gave him his start in journalism by hiring him, when he was still literally almost fresh off the boat in 1948, as assistant editor of his family-owned Troy (Ill.) Tribune. Klotzer held the position until 1951.)

What experiences forged this orientation? More specifically, when did it form?

Sitting at his dining room table in a room crowded with file cabinets and papers, Klotzer looked this reporter in the eye and deadpanned, “November 1, 1925.”

A trace of a smile followed. Then he added, “The social compact between people is now considered left. But if you believe in Judaism, there’s no alternative. The commitment to justice is paramount.”

That commitment can exact a price, of course, and Klotzer at times has been forced to pay it. Receiving a draft notice in 1951, during the Korean War, he thought he would be excused when he explained he was the sole support of his elderly parents. But when the chair of the draft board made a racist comment during his interview, Klotzer let him know what he thought of it.

He spent the next two years in the Army.

A boyhood experience in Shanghai may be telling in this regard. While Klotzer was a teenager, a group of anti-Semitic Russian refugees beat him up once after work. A Jewish man who became aware of the situation invited him to join a boxing club. Klotzer went on to fight 12 matches, winning the first 11. His last bout — for the lightweight championship of Shanghai – ended in a draw.

“While I consider boxing a sport that should be banned,” he later wrote, “I must confess that the exercise and training instilled in me a lasting measure of self-confidence.”

Rita Csapo-Sweet is a filmmaker and University of Missouri St. Louis faculty member who became close to Klotzer while making a documentary about him a couple of decades ago. Klotzer has an appealingly courtly, old-world manner whose impact is reinforced by his German accent, and “is a very kind person,” she said in an interview. But he is “no one you can push around. There’s a border with him, a line in the sand.”

With that kind of makeup, at least in Klotzer’s case, goes a quiet pride and self-confidence, as well as independence of judgment and action. Physically, those characteristics can be seen in his posture and gait. Verbally, they’re in his unwillingness to describe himself as a “Holocaust survivor,” Rushfinn said. And in the details of his life story, they are everywhere.

Klotzer was still a teenager when, due to “family dynamics,” he effectively became the head of his family, he told me. (His mother, he says, was a down-to-earth woman who ran a toy store in Berlin, his father a well-liked actor and poet with tendencies toward fabulism and groundless optimism. By the time they reached Shanghai, Klotzer’s father was already in his late 60s, equivalent to what now might be his 80s.) In Shanghai Klotzer’s schooling, except for some business classes, ended at 17, at which time he got work to help support the family. After the family had moved to St. Louis, they spent only a week in the “horrible” hotel selected for them by the Jewish Family Services Agency before Klotzer moved them – without permission – to a better one.

It can hardly be a surprise, then, that after everyone Klotzer consulted told him that a magazine about social issues in the Midwest would surely lose boatloads of money, he started FOCUS/Midwest anyway. (The advisers proved correct.)

Nor should it be a surprise that in 1954, when he founded a short-lived newspaper for the St. Louis Jewish community, he justified the venture by arguing that the existing publication “was just a house organ for the Jewish Federation.” And it also might have been predicted that when he started the St. Louis Journalism Review, he arranged for it to be funded out of a separate company, his FOCUS/Graphics typesetting firm, so Review advertisers – precious few that there were – could not influence the publication’s coverage.

“Charles always had a firewall between advertising and the news and editorial sections of the paper,” Csapo-Sweet noted. “In today’s world of corporate ownership of everything, he still stands out as a kind of example of how journalism can be done right.”

Klotzer’s own account of his life story, published in the GJR three years ago, is notable not only for the story it tells but for the understated, just-the-facts style in which he tells it.

A documentary film released in 2002, “Shanghai Ghetto,” depicts the environment in which the Klotzer family lived for nine years as a seriously overcrowded, unsanitary, diseased, impoverished hellhole. In his written account, Klotzer acknowledges that some of those who saw the film “wondered that the impression they had from me was not as depressing as the film.”

But for him, it really wasn’t that bad, he insisted in one of our three conversations in his dining room. “My own experience was much milder than what I saw there,” Klotzer said. “It wasn’t scary to me, it wasn’t exciting. It wasn’t traumatic.”

(The room – crowded with stacks of papers, file cabinets, and boxes of awards and other memorabilia – is clearly much more about work than the consumption of food. Other rooms are stacked with book cases, overflowing and even reaching to the ceiling. Walls not covered by books are adorned with family photos, Judaic art, and prints by the likes of the Post-Dispatch editorial cartoonist Bill Mauldin and the prominent late artist LeRoy Neiman, who made them for covers for FOCUS/Midwest. The overall impression is not one of chaos, but it’s clear that learning and the preservation of history have lapped order as priorities in this house.)

Klotzer enjoyed an active membership in the Boy Scouts in China, he said, as well as in a “Tikvah” club (Tikvah means “hope” in Hebrew) where he socialized with other boys and young men, some of whom went on to careers of distinction in America and Israel. The Japanese occupiers were not hostile to the Jews. Above all, he – and everyone – knew their situation would not last forever. The war was going to end.

Her father, Rushfinn told me, simply had an ability, “based on his personality and outlook,” to “not absorb or act on the trauma.” She is grateful for this, she said, “because I think it helped in my upbringing to not have a father who was impacted by the Holocaust and Shanghai ghetto life in the same way as others.”

In describing the family’s Shanghai years Klotzer does write touchingly about his mother wistfully eyeing a cup of coffee she could not afford to buy, and about her selling her wedding ring to pay for his tuition to classes at Shanghai Business College. But there is no pathos in his description of the Shanghai years for himself, despite all the obvious hardships.

Likewise, in discussing his publishing ventures in St. Louis never mentions how hard he and Rose worked to simultaneously raise three children and put out two money-losing publications and run a typesetting business. Nor is there one word in this account of any of the honors or awards he has won.

After Klotzer saw the first cut of Csapo-Sweet’s documentary about him, he was upset, she recalled. He thought Rose deserved more credit and screen-time. So Csapo-Sweet added more Rose.

Klotzer met Rose Finn (don’t let the last name fool you, she was Jewish) at a Hillel (Jewish student union) event in 1948 at Washington University, where she was a student. A native St. Louisan, she was extroverted, nature loving, and witty. Soon thereafter he took her to a synagogue dance and found he liked the “very sensitive” way she responded to his lead. Not long after that he asked her to marry him.

No, she said. She wanted to finish her education. Five years later, with her M.A. in social work in pocket, she relented. Everyone who spoke to the GJR about Klotzer said he is nothing if not persistent. (In that regard, it might also be noted that in 1954 Klotzer earned his own B.A. from Washington University in political science and English, having taken most of his classes at night from 1948 to 1951 and just his final year full–time. The thanks for the final year go to the G.I. Bill and, in turn, to the draft board chair who didn’t like his attitude.)

Rose made one serious mistake during her many years of schooling, he told me in his customary wry deadpan. “She learned typing.”

That gave her the skills to help him with his typesetting business and his publications. So Rose, dropping her social work aspirations, joined Klotzer in his business ventures –and enabled them, actually, because paying a non-family member for what she did would have been impossible.

It was not a reluctant partnership, observers agree. Rose was all in. In fact, Csapo-Sweet so deeply admired the collaborative relationship she saw between the Klotzers that it was one of the reasons she and her late husband “fell in love” with them, she said, and that she chose some 25 years ago to make her documentary about them. (“Who’s Minding the Media” can be found on her website at https://www.csapo-sweet.com/film-video/. She is currently updating it.)

Dancing with his wife was one of the great pleasures of Klotzer’s life. “In dancing with Rose I felt like the conductor of a symphony,” he told me. “We both followed and led.”

The couple would dance at Casa Loma or one of the other ballrooms in St. Louis on a monthly basis, he recalled. They won at least one tango contest.

Dancing also fed his self-confidence, Klotzer said in a separate interview many years ago. As did, of all things, table tennis.

Klotzer took up the sport decades ago and became accomplished. For years he played for hours at a time three days a week and traveled for tournaments. In his 80s, he was reportedly ranked ninth in the country for his age group. He loved not only the sport and the competition but the involvement with people with backgrounds and experiences he never would have otherwise met.

Mark Sableman is a St. Louis lawyer who is also one of Klotzer’s longtime associates and close friends. “There is a joyfulness, friendliness, and attractiveness to Charles that belies all of the hard experiences of his life,” he said.

“People like him,” he added. “That’s why they want to help him. He has charisma.”

Jessica Z. Brown-Billhymer is a Gateway Journalism Review board member who has helped organize the annual First Amendment Celebrations for the GJR since their inception in 2011.

“The reason I’ve done so much for the Review is because of Charles Klotzer,” she said flatly.

“He is a very humble man. And genuine. And charming. And he knows what he wants. He sticks to what he believes is going to be right for the Review.”

Notice how that thought ends – with Klotzer’s support not for himself, but for the Review. Perhaps this is his most distinguishing trait, intimates say: With Klotzer, it’s not about Klotzer.

During his days in Shanghai it was about taking care of his parents. In St. Louis, it’s been about, first his wife and children and parents, then his publications and ideas, which is another way of saying his community. (Note: Klotzer’s parents died in their 80s, his father in 1962, his mother in 1973. Both had lived the rest of their lives in St. Louis after arriving with Charles in 1948, and both, as previously noted, had depended on him for financial support.)

As the GJR has attracted its roster of top journalists to speak at its First Amendment Celebration over the years, many people in Klotzer’s position would have made it their business to talk with them personally. The opportunity to enjoy at least a bit of reflected celebrity, if not do some network building, would have seemed like an obvious perk.

Klotzer shakes his head. He can’t remember ever doing anything of the kind.

Neither Rushfinn nor Csapo-Sweet is surprised.

Said Rushfinn: “I don’t think it even occurs to him to have people pay attention to him just for him.”

Said Csapo-Sweet: “That’s why I have to make the movie, especially in this period of cynicism and despair about the media.

“A man like Charles L. Klotzer has to be celebrated.”