In the 20 years since I started the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, we have sought to facilitate great reporting on topics too often ignored. Over those years we have also built a network of schools, community colleges and universities, working with them to make strong journalism the basis for constructive debate on the big issues that affect us all.

The 1619 Project is a powerful example of what can be accomplished — as is demonstrated in the experiences in actual classrooms detailed below.

The project continues to be the topic of fierce debate, the focus of critiques by eminent historians, and attempts by politicians to make it a cultural wedge issue as to what can and should be taught in schools.

The 1619 Project wasn’t perfect. Journalism rarely is. Lead author Nikole Hannah-Jones and The New York Times have both acknowledged that some of the arguments in the essay were overstated, especially about the extent to which defense of slavery was an impetus for the American Revolution. But the larger point, slavery’s central role in the shaping of America and its continuing legacy today, is beyond dispute. So too the egregious misrepresentations of slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow that were the stuff of standard history textbooks in this country for generations.

We assumed The 1619 Project would be controversial, that it would generate debate among historians and spark the kind of attacks we have seen. The surprise to us has been the overwhelmingly positive response to this initiative in K-12 classrooms, school districts, and college campuses.

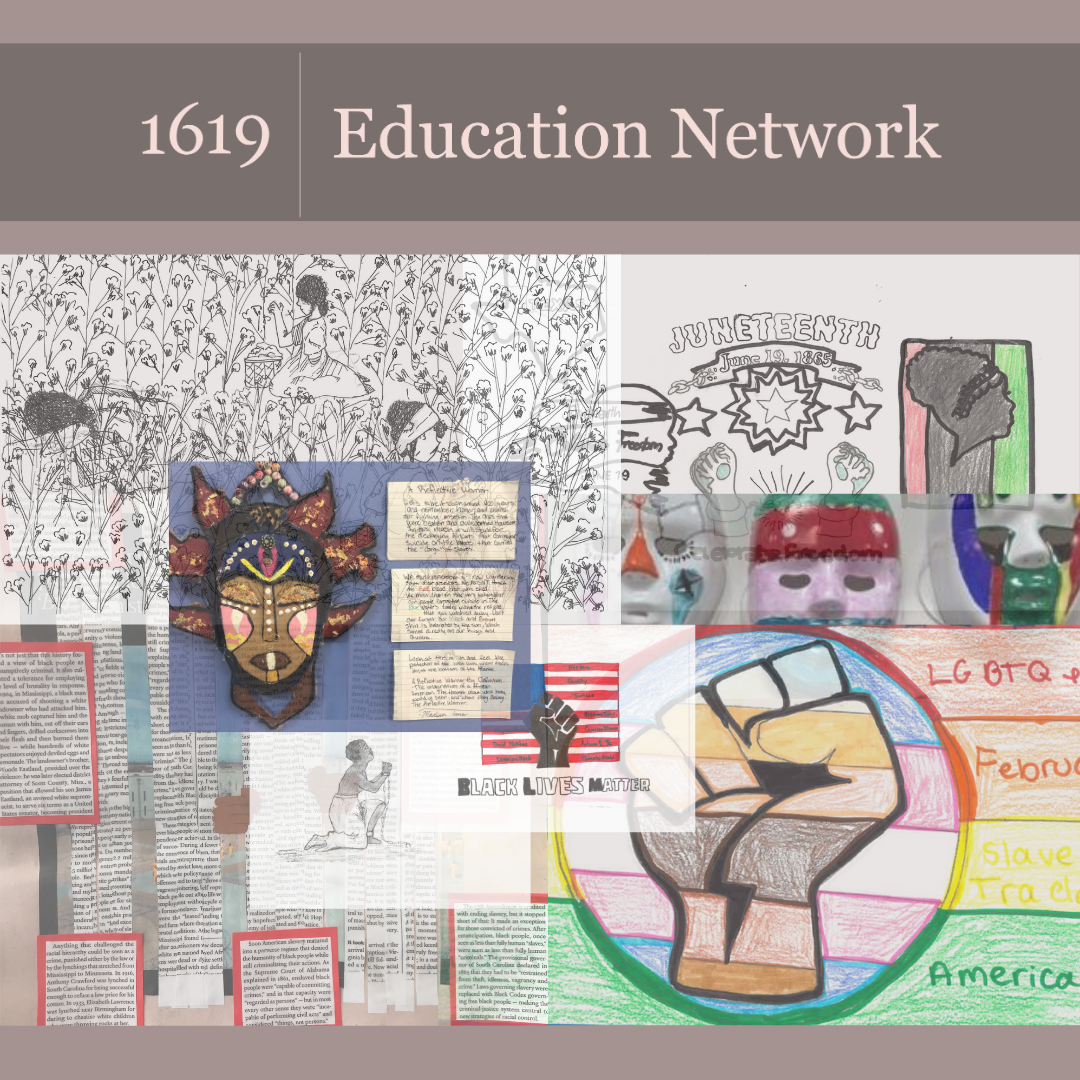

Working with The New York Times and Hannah-Jones to engage students with the issues raised by The 1619 Project has led to unforgettable encounters with students across the country, many of them captured in the testimonials and examples of student art that follow.

1619 at R.J. Reynolds High School

One of the most moving experiences for me was the opportunity to interview Hannah-Jones in a school assembly at R.J. Reynolds High School in Winston-Salem, N.C. In preparation for that visit, in October 2019, students from history, art, dance and other classes had engaged in the lesson plans we had written; on the day of Hannah-Jones’s visit they lined up to share their work.

“To say that moment was powerful doesn’t do it justice,” said Pam Henderson, director of magnet programs for Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools. “Our silent students, our quiet artists, our outspoken activists — they flocked to her, as she was a voice that spoke loudly to them. They created art inspired by her work and by the work of others taking part. They had conversations with family and friends, broaching topics often glossed over. They were brave because they were witnessing bravery and unapologetic inquiry.”

I was a student at Reynolds in the late 1960s, at a time when Black students numbered in the low dozens. My mother, as a member of the local school board in the 1970s, helped lead the fight to bring true integration to that school system, thanks to a mandatory busing program that at its peak included nearly 40,000 students.

Within a decade that initiative was dead, the victim of white backlash, conservative court rulings, and a federal government that turned its back. Today’s Reynolds is a predominantly Black school and the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County schools are among the most segregated in North Carolina.

On the evening of her appearance at Reynolds, Hannah-Jones spoke to an overflow and diverse audience of nearly 1,000 people at Winston-Salem State University. She gave them an appalling litany of discrimination today, especially as to the yawning gap in advanced-placement and other educational programs between predominantly white schools in my hometown and those that are predominantly Black.

“Part of this conversation may make you feel uncomfortable,” Hannah-Jones said that night. “I certainly hope it does.”

Debate will go on

The 1619 Project and the curricular materials we’ve produced are not the final word in a debate that will no doubt go on. But against the backdrop of so much mis-teaching of American history they are a welcome corrective, and overdue.

We have seen this again and again. Students moved by the project to express themselves creatively in performance. Students applying themselves to historical inquiry. Students inspired by the centering of the Black experience as critical to the idea of America.

The grassroots demand among teachers for a better way to reckon with our nation’s history of slavery is powerful. Thousands, from every state, used our curriculum. Since the project launched:

● Over 1 million people have engaged with the reading guides we published in 2019;

● 541 educator partners in over 30 states developed projects that connected Project themes and resources to over 25,000 students in pre-K-12th grade and over 2,500 adult learners through Network-building and professional development programs;

● Over 100 curricular resources developed by Center staff and educator partners have been published to the Webby award-winning website 1619education.org, which has been viewed over 400,000 times by people in all 50 states and Washington, DC;

● We have led over 200 trainings and workshops for some 15,300 teachers, in-person and online.

Historical scholarship, like journalism, is often fraught with controversy, as people of good faith can disagree over the interpretation of historical facts. That is certainly the case regarding the legacy of slavery for American democracy and our national identity. This is not a new controversy. Americans have been debating the effects of slavery for much of the nation’s history. The Pulitzer Center’s education work is intended to help students explore sensitive topics themselves, not to guide them to a specific point of view.

The testimonials and examples that follow will make you feel inspired, I hope — by teachers and students across the country engaging honestly with real issues, and by the powerful work of journalism that helped bring those conversations about.

Engaging with 1619: Testimonials from teachers and students

Rebecca Coven, former teacher, Sullivan High School, Chicago; now director of school programs at Mikva Academy

After reading, analyzing, and learning from The 1619 Projectin our 10th grade humanities class, students produced their own version of The 1619 Projectin which they researched and analyzed how the legacy of slavery still impacts their communities — in Chicago, in their neighborhoods, and our school — today. The Sullivan 1619 Project was researched, written, illustrated and produced (visuals, editing, layout, etc.) completely by students.

My students might have said it best in their introduction to The Sullivan 1619 Project: “In the process of creating [our] own magazine, [we] were able to see how many of the issues discussed [in The 1619 Project] could be seen in our own communities within the city, neighborhood, or school… Amongst all of these inequalities, [we] had the opportunity to see the resilience, determination and courageousness of people of color… The year 1619 was also one of the first times a marginalized group fought back on this land and resisted… Because of the resilience of enslaved Africans, other groups of people who are marginalized today and who have been marginalized throughout history have been given the opportunity to fight back, given hope by the success of others before them.”

Anne-Michele Boyle, Global Citizenship Teacher, Whitney Young Magnet High School, Chicago

The 1619 Project and the accompanying Pulitzer Center educator resources have been instrumental in my ability to effectively teach the historical roots of racism and the too-often-undertold histories of the contributions of Black Americans. For the second school year in a row, my students and I have engaged in robust dialogue and spirited discussions on racism, history, activism, our flag and what it means to be an American because of The 1619 Project and the Pulitzer Center. I am hopeful about the future of America because these challenging, yet vitally important 1619-inspired conversations are happening in classrooms throughout our country.

CeCe Ogunshakin, 8th grade arts teacher at School Without Walls at Francis Stevens in Washington, DC

The 1619 Project was very eye-opening to myself and my students. It caused students to reflect and engage in meaningful dialogue. I presented the content and discussion to students through a Socratic Seminar, where a student moderator used questions by the Pulitzer Center to facilitate discussion in my classroom. Although some students might not have agreed with some of the essays, students were able to learn about and respect each other’s perspectives, as well as the perspectives of the writers.

Stella, a Benjamin C. Banneker High School student at the 2020 symposium on 1619, with the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC

I will take what I learned from 1619 and pair with my advocacy and activism work. I don’t feel that I can end how Black people are being degraded every single day, but I can join forces with other organizations and my community to demand our respect and get what we deserve.

Abigail Henry, Philadelphia charter school history teacher, was among a group of educators who worked with the Pulitzer Center to incorporate the expanded, book-length version of 1619 for classroom use. She divided the class into two groups, one group reading an essay from “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story” and the other a set of essays on July 4 by the conservative journal National Review — and then debating the question as to which year was more important in American history, 1619 or 1776.

The beautiful part about this debate is the conversation that happened after. Many of the students truly felt that 1776 was more important AND they still believed 1619 should not be banned from teaching in schools.

One of my biggest frustrations regarding any criticism of The 1619 Project is the framing of it, [with a focus on issues like white guilt or privilege instead of] celebrating how The 1619 Project provides a means for Black students to investigate the struggles and achievements of their ancestors after the arrival of enslaved Africans.

My student [population is] 99.9 percent Black. Through the past three weeks they have been asking some of the best history questions I have ever experienced.

Shea Richardson, curriculum supervisor, East Orange (NJ) School District

The impact that The 1619 Project had on our scholars is one that will last beyond this school year. It gave our scholars a sense of identity and a closer connection to the history of the great cities of Newark and East Orange [New Jersey]. More specifically, it allowed our scholars to learn more about their own identities by understanding the power of local history.

A high-school English language arts student in Woodburn, Oregon, reflecting on a unit created as part of The 1619 Education Network

The 1619 Project was a sight into the truth. A lot of this history is hidden, banned, or erased, and that’s exactly why it’s so important that we learn this history. Students are learning the truer history of America. 1619 isn’t a whitewashed or diluted book; it’s the full detail with nothing hidden. Learning this history helped me connect the dots with a lot of things.

Jocelyn Aguilera, history teacher, John C. Fremont High School, Los Angeles, CA

The 1619 Teacher Resources have had a profoundly positive impact on my students here in South Central LA, fostering an environment where students feel comfortable discussing challenging topics related to race, slavery, and social justice. This has empowered them to develop empathy, think critically, and engage in conversations that extend far beyond the classroom. I’ve witnessed a remarkable transformation in their perspective on history and their own roles as active citizens.

Jon Sawyer is founder and senior advisor at the Pulitzer Center, education partner to The New York Times on The 1619 Project.