Police misconduct is a leading cause of wrongful convictions in the United States. Just over 2,900 people have been exonerated in the U.S. since 1989 according to data from the National Registry of Exonerations. That amounts to 25,900 lost years for those stuck behind bars.

Over 37% of those cases involve police misconduct, and over half of all exonerations involve misconduct by prosecutors or police.

That means police and prosecutor misconduct is responsible for over a thousand documented wrongful convictions unearthed in the United States since 1989.

The police misconduct includes shoddy police work, coerced confessions, use of unreliable jailhouse informants, misleading lineups and photo arrays and a failure to turn over exculpatory evidence as required by law.

People of color represent over 64% of those wrongfully convicted nationally, and disproportionately experience police misconduct. 72% of all instances of police misconduct that lead to wrongful conviction in the U.S. imprison people of color, mostly Blacks.

“There’s a problem with some police all over the country,” said Ken Otterbourg, researcher at the National Registry of Exonerations. “The two most common types of police misconduct are probably misconduct during interrogations and also failing to disclose exculpatory evidence.” He based that assessment on the Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent report on the National Registry of Exonerations website.

Police and prosecutor misconduct high in Midwest

Police misconduct accounts for an even higher percentage of wrongful convictions in the Midwest than the rest of the country.

In Illinois 75% of all wrongful convictions since 1989 involved police misconduct. In Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska, the statewide rate of police misconduct among wrongful convictions is also high — Missouri (49%), Kansas (57.1%), Nebraska (66.7%).

The Exoneration Project, based in Chicago, and the Midwest Innocence Project, based in Kansas City, Missouri, lead the efforts in those states to exonerate those wrongfully convicted.

In Missouri there were 15 total exonerations for murder where the cause of the wrongful conviction was official misconduct, according to the National Registry. That was half of the 31 murder exonerations. All told, there have been 51 exonerations on all charges in Missouri.

Two wrongful convictions in Missouri have grabbed headlines in recent months – Kevin Strickland from Kansas City and Lamar Johnson from St. Louis. Strickland finally was released just before Thanksgiving after 43 years in prison, the longest period of wrongful imprisonment in Missouri history.

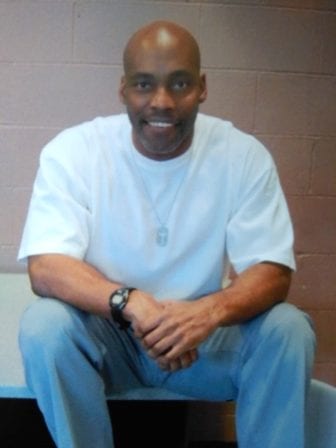

Lamar Johnson is not so lucky; he’s still incarcerated.

Attorney General Eric Schmitt has tried to keep both men in prison even though the prosecutors’ offices that had convicted them had reviewed the evidence and concluded they were not guilty.

Kevin Strickland: police manipulate eyewitness

Strickland, wrongfully convicted in 1979, was released on November 23, 2021. From the beginning no physical evidence linked Strickland to the crime scene of a triple murder. Moreover a convicted gunman said Strickland was innocent and the only eyewitness recanted her identification.

Strickland, who is Black, was initially tried by a jury that included 11 whites and 1 Black. All 11 white jurors voted to convict, but the Black juror refused. The prosecutor reportedly told Strickland’s attorney he had been “careless” allowing a Black on the jury and wouldn’t make that “mistake” again. He didn’t. The prosecutor used peremptory challenges to strike the last four Blacks from the jury pool in the second trial. The all-white jury took one hour to return a guilty verdict.

The conviction resulted from a mistaken eyewitness identification by the key witness, Cynthia Douglas, who was shot and left for dead at the murder scene.

The night of the murder, Douglas said she could only identify two men, both of whom were convicted of the murders. Strickland wasn’t one of them.

Douglas picked out Stickland from a lineup the next day. Douglas later recanted her testimony, explaining that police manipulated her into selecting Strickland from a lineup.

Douglas’s friends and family said at a recent hearing that not long after Strickland was convicted, Douglas realized she had the wrong guy. For years she tried to get people to listen without success.

In 2009, she wrote an email to the Midwest Innocence Project saying, “I am seeking info on how to help someone that was wrongfully accused, this incident happened back in 1978. I was the only eyewitness and things were not clear back then, but now I know more and would like to help this person if I can.”

Douglas died in 2015, but eventually Jackson County’s progressive prosecutor, Jean Peters Baker became convinced of Strickland’s innocence.

At a court hearing this fall, Douglas’ mother, Senoria Douglas, recalled her daughter saying, “Mother, I picked the wrong guy!”

Attorney General Schmitt’s office claimed in court that Douglas’ email might not have been authentic and that Strickland had spent 40 years “dodging” accountability for the murders. Strickland countered that he was not going to take accountability for murders he had not committed, even though the men who had pled guilty already had been released from prison.

On November 23, presiding Judge James Welsh ruled that Douglas’s recantation was credible and the conviction could not stand. Strickland was released under a new law that made it possible for prosecutors to seek the release of prisoners their office had wrongfully convicted.

Still, Strickland won’t receive any money from the state since Missouri only compensates those exonerated by DNA evidence.

“Kevin’s case is just one example of how much the system values finality over fairness, and how, even when we change the system, the system fights back,” tweeted Tricia Rojo Bushnell, executive director of the Midwest Innocence Project. “But as hard as the fight is, it is worth it.”

Lamar Johnson: police and prosecutor paid $4,000 to eyewitness

St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner has tried since 2019 to get Lamar Johnson a new trial after 26 years behind bars for the murder of Marcus Boyd. Two gunmen, wearing “Ninja” ski masks that showed only their eyes, shot Boyd dead on his front porch in 1994. The shooters had accused Boyd of keeping more than his share of profits from drug deals. Greg Elking was the one witness to the shooting.

Here is the police and prosecutor misconduct detailed in Gardner’s filings and briefs filed by the Midwest Innocence Project:

- Elking at first said he could not identify either of the killers because of the masks. Later, the lead detective on the case, Joseph Nickerson, told Elkin that police knew Johnson was the killer and that the state could help Elking with moving expenses if he cooperated with the prosecution. Elking initially failed to identify Johnson in a series of lineups. Elking later said the failed lineup put Det. Nickerson in a “foul” mood and Elking felt like he had “let everyone down.” Elking and Nickerson got into an elevator and Elking asked Nickerson to tell him the lineup position numbers of the men that Nickerson believed killed Boyd. Nickerson then told Elking the men were in position #3 and position #4. That implicated Johnson.

- Det. Nickerson and Assistant Circuit Attorney Dwight Warren arranged to pay more than $4,000 to Elking but failed to disclose the payments to the defense. In a letter to the Rev. Larry Rice several years after the conviction, Elking wrote, “The detectives and me had a meeting with the Prosecutor Dwight Warren and convinced me, that they could help me financially and move me & my family out of our apartment & relocated use (sic) in the County out of harms (sic) way. They also convinced me who they said they knew murdered Marcus Boyd.”

- Nickerson authored four different false police reports based on the statements of four different witnesses. Years later, all four witnesses reviewed the reports and swore under oath that they never said what Nickerson had attributed to them.

- The two actual killers have filed affidavits saying Johnson was not involved in the murder.

- A jailhouse informant, William Mock, was essential to the conviction, but he lied in court about his criminal record, his motivations and whether he had ever before testified as a jailhouse informant. Prosecutors knew he was lying.

Mock testified that he had heard Johnson incriminate himself in a nearby cell in City Jail after he was arrested by police. But Mock left out important parts of his 60-page arrest record, left out the help he expected from prosecutor Warren, and failed to disclose he had given testimony as a jailhouse informant in a Kansas City murder case only two years earlier.

Mock had written to prosecutor Warren in June 1994, “I don’t believe that anyone in the legal system will disagree with the value of my testimony in this trial as opposed to the conviction that I am now serving. I am willing to testify as long as I don’t have to return to the Department of Corrections once I testify. I can’t I won’t live in protective custody or any institution after I testify. I am serving a five year sentence for CCW, which I have been serving since 1993. I feel my testimony is worth a pardon by Mr. Carnahan or a reduction in my sentence…I will uphold my end of the situation as I am certain you will fulfill your obligations to me.”

Despite evidence of innocence, Johnson remains behind bars. The Missouri Supreme Court ruled that state law did not permit a prosecutor to move for a new trial for a person their office had convicted. The Missouri Legislature has since passed a law permitting the prosecutor to take those steps — the law that helped Strickland get out of prison — but the law has not been applied to Johnson.

“There is no doubt that Lamar Johnson is innocent,” Midwest’s Bushnell tweeted. “And no one is arguing he is not. But still, he languishes.”

Black clergy and St. Louis’ Black police union called last summer for Nickerson to be fired from his current police job in St. Louis County because of his role in the Johnson case.

Nickerson calls Gardner’s allegation about him “baloney” and says he still thinks Johnson is guilty. Prosecutor Warren also maintains Johnson is guilty and says the $4,000 in payments to the eyewitness were for witness

protection.

In Chicago exonerations come in the dozens

In Chicago, unjust convictions are not just isolated cases but are uncovered in the dozens from the work of corrupt police squads. Sgt. Ronald Watts’ tactical unit at Ida B. Wells apartment has reached 115 exonerations and counting. CPD Detective Reynaldo Guevara framed about 50 mostly young Latino men on the city’s northwest side. And Burge’s homicide squad tortured hundreds of mostly Black suspects from the 1970s-90s before he was stopped.

Illinois has had 363 total exonerations since 1989, with 271 of them having grown out of police misconduct. 177 of the exonerations were murder cases and 133 of those grew out of police misconduct.

Illinois courts have recently thrown out 115 unjust convictions based on the fabricated police work of a tactical team headed by disgraced Sgt. Ronald Watts. It is one of the biggest police scandals in Chicago history.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot has called Watts “the Burge of our time,” a reference to Chicago Commander Jon Burge whose homicide squad physically tortured Black men into making false confessions.

The Exoneration Project calls the Watts scandal “nothing short of a decade-long criminal conspiracy of extorting drug dealers, stealing narcotics, planting evidence, and falsifying charges.”

Watts and his crew terrorized the Ida B. Wells housing project for the decade leading up to 2012, but the ramifications of that streak of police misconduct are still playing out in Chicago courtrooms. Another 83 cases will go before a judge for possible exoneration in January, 2022.

Ben Baker spent 9.5 years in prison on drug charges for a crime he did not commit. While exculpatory FBI documents were available during Baker’s trial, they were hidden from his lawyers, causing him to be wrongfully convicted in 2006. He was exonerated in 2016.

Joshua Tepfer, Baker’s attorney at the Exoneration Project, tweeted, “There is no one more corrupt in Chicago history than Ronald Watts.” “Ben is just one of…I don’t think it would be exaggeration to say hundreds of people that are victims of this corrupt crew.”

“It was Watts law, not Illinois law,” Baker said of Watts’ crew in an interview with the Exoneration Project. “Either you pay, or you went away. That was the rule.”

In 2012, Watts and another officer were indicted by federal authorities for taking a bribe from an informant and later pleaded guilty. Documents have since revealed that Watts and members of his team were running a “protection racket” for more than a decade, planting evidence and fabricating charges against Black Southside housing project residents while facilitating their own drug and gun trade.

The Illinois Appellate Court said Watts and his team were “corrupt police officers,” perjurers, and “criminals.” It criticized the city’s police disciplinary bodies for failing to do anything “to slow down the criminal” police officers during a decade of corruption.

Now, three years after the mass exonerations started, the City’s latest police oversight board—the Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA)— has failed to act and has retained a dozen officers tied to the dismissed case as active members of the police force.

Tepfer said that in Baker’s case, “The judge accepted the testimony of four sworn police officers over a black man.” To this day, all three officers who backed up Watts in Baker’s trial remain on the force.

50 more people framed

CPD Detective Reynaldo Guevara is accused of framing 50 innocent people for murder, mostly young Latino men from the city’s Northwest Side. Twenty have already been exonerated and the investigation of 30 other cases continues. Guevara pressured eyewitnesses to crimes to make false identifications and beat false confessions from suspects, investigations have shown.

Jose Montanez is one of Guervara’s victims. He spent 23 years incarcerated for a crime he did not commit. He and his co-defendant Armando Serrano were wrongfully convicted for murder and each sentenced to 55 years in prison.

Neither man confessed, and there is no physical evidence tying them to the crime. The sole piece of evidence against the two was the

false testimony from a jailhouse informant coerced by Guevara.

The jailhouse informant later recanted, stating “My false testimony was given as a result of threats, intimidation, and physical abuse by Detective Reynaldo Guevara.” Moreover, prior to their exoneration, a 2015 report on a review conducted by the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office found that Montanez and Serrano were “more likely than not actually innocent.”

“This was no mistake; Detective Guevara framed these innocent men,” Russell Ainsworth, Montanez’ attorney at the Exoneration Project, said in a statement. “Sadly, dozens more innocent Guevara victims remain incarcerated for crimes they didn’t commit. We will not rest until every single one of them is exonerated,” Ainsworth said.

Last year the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office announced it was conducting a “comprehensive review” of all convictions connected to Guevara.

Burge’s midnight crew

John Burge, the former Commander of the “Midnight Crew” tortured over a hundred Blacks in the 1970s and 1980s, forcing many to give false confessions through beatings, electrical shocks, and more.

The Crew was known to point guns in the mouths of victims, smother them with plastic typewriter covers, and burn them with cigarette lighters. 118 Black victims have been documented, with many more still unidentified. Only in 1993, ten years after his crew’s rampant misconduct was first brought to light, was Burge fired from the CPD. Federal prosecutors later sent him to prison.

James Kluppelberg spent 24 years in prison for an alleged arson and 6-person homicide on the South Side of Chicago that he did not commit. He was tortured in 1984 by detectives working under Burge.

According to the Chicago Police Torture Archive, a self-described human rights documentation of Burge’s violence against over one hundred Black people from the 1970s – 1990s, Kluppelberg was tortured into giving a false confession and beaten to the point that his kidney was lacerated and he urinated blood.

“They laid me face down on the floor and they started punching me in my back and using the heel of their feet in the back kidney area,” Kluppelberg said. “They knew what they were doing. And they did it anyway for their own personal gain,” Kluppelberg said of the officers who tortured him in a video produced by the Invisible Institute. “They used my case to build their careers,” he said.

While Kluppelberg was convicted of arson and murder, CPD ultimately concluded that the fire was an accident. Still, Kluppelberg spent 24 years behind bars.

Biggest problem in the criminal justice system

Bushnell, director at the Midwest Innocence Project, the organization that represents wrongfully convicted prisoners in Missouri, said in an interview that she sees police misconduct as the biggest problem in the criminal legal system, referring to it as a kind of “open secret.”

Sean O’Brien, who has represented many men who have been wrongfully convicted in Missouri, said in an interview that one cause of unjust convictions in Missouri is that the “rural public defender system has been exceedingly weak in terms of quality of representation.” Missouri has an underfunded legal representation system: it ranks 49th in the country, according to National Legal Aid and Defender Association statistics.

O’Brien also said more independence is needed to look into prison homicides and prison violence to avoid corruption: “Prison guards are not well-trained or well-compensated. They are vulnerable to corruption so investigations need to be done by outside agencies and individual officers from outside agencies should be screened for independence from connections to the corrections complex.”

The 15 exonerations in murder cases that flow from police misconduct include coerced confessions, unreliable use of lineups and photo arrays, failure to disclose exculpatory evidence, reliance on self-interested confidential sources and failure to follow up on alibi evidence.

Elizabeth Tharakan is a PhD student at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, where she studies Mass Communication and Media Arts. She is also an attorney licensed in Missouri, Colorado, New York and the District of Columbia.