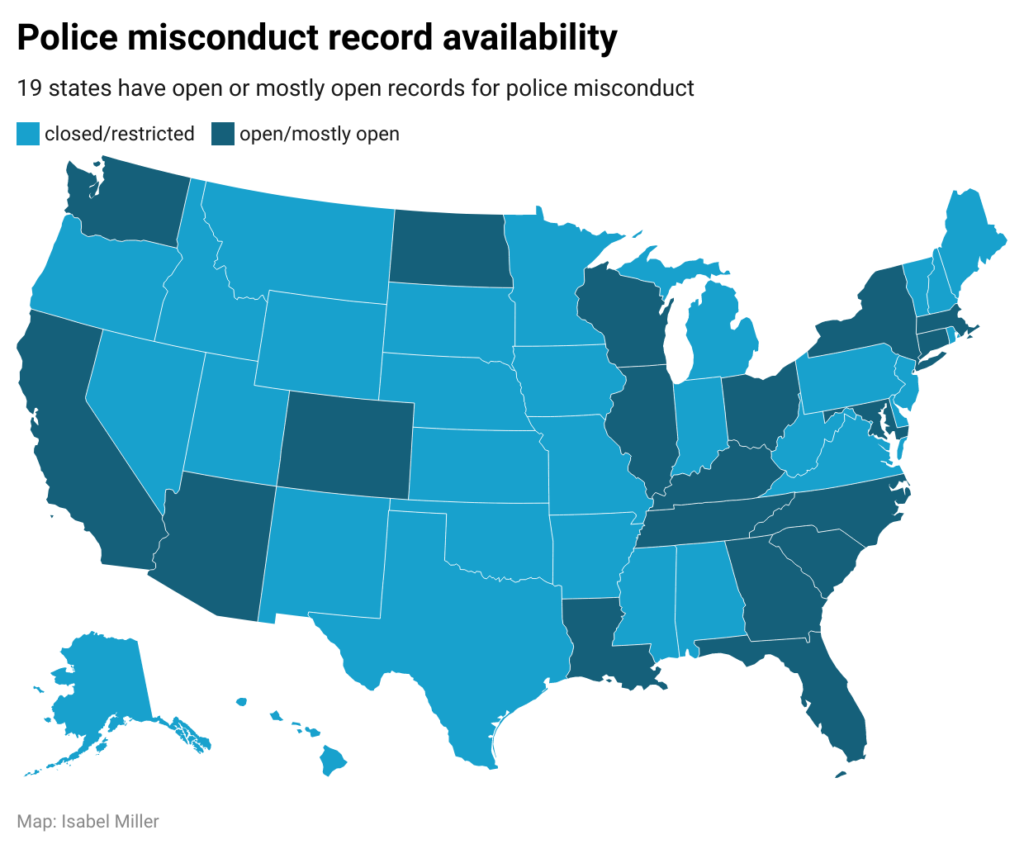

Police misconduct records are either secret or difficult to access in a majority of states — 32 of them including Washington, D.C. But the breeze of openness is blowing. Seven big states have opened records in recent years — California, New York, Illinois, Colorado, Massachusetts and Maryland.

Nineteen states now have laws that allow these records to be mostly available to the public — up from 12 a few years ago.

Legal experts say transparency of police misconduct records is one of the keys to police reform. David Harris, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh, put it this way: “One thing that has changed is greater transparency. We have seen a number of jurisdictions enhancing and changing the way police misconduct records have been handled. You can’t have real accountability with the public unless you are willing to share information.”

The modest uptick in openness is the result of a combination of court decisions and reform laws passed since the murder of George Floyd. New York, Massachusetts, Colorado, Oregon and Maryland enacted laws in the past year opening records that were previously closed. California passed a law opening some records in 2018 and came back with a broader open records law this past fall.

In Illinois, the Invisible Institute won a court decision in 2014, Kalven v. City of Chicago, granting public access to misconduct records by striking down exemptions law enforcement agencies had claimed when denying public record requests.

New York state repealed Section 50-a of the state’s civil rights law last year and this year made more than 300,000 police misconduct records public. Indiana passed a bipartisan police reform bill last month that publishes the names of officers decertified for misconduct.

However, there are still tall barriers to accountability, even in some of the states that have begun to open up.

In Illinois, a widely touted police reform law passed this year included a provision that closed the state Professional Conduct Database of officers who resigned, were fired or were suspended for violating department policy. Not only are the names withheld but also the supporting documents. To get statewide records, a person would have to contact each of the almost 900 police departments and request these misconduct records individually.

In Pennsylvania, Gov. Tom Wolf signed a bill into law in 2020 that created a database to track police misconduct statewide and force agencies to check the database before hiring an officer. But the legislature closed the database to the public.

Indiana’s bipartisan law passed this spring required an online listing of the names of all officers disciplined, but closed the much more plentiful investigations that don’t end in punishment. Colorado opened records but its law was not retroactive. Oregon created a database of officers disciplined but did not open records of investigations that didn’t lead to discipline.

In New York the repeal of 50-a seemed to throw open the window to a new era of transparency. But police departments and police unions — with the assistance of local judges — have been slamming the window shut again.

Police departments across New York have maintained that unsubstantiated complaints of misconduct — in other words complaints that can’t be proven true or false — should be closed records because their release would violate officers’ privacy. Most complaints of misconduct fall in the unsubstantiated category.

Police departments and police unions also have argued that the repeal was not retroactive, so all misconduct records from before the official date of the repeal in June, 2020 are closed, they claim.

And there are other bureaucratic hurdles to release. The public records group MuckRock filed a public record request for police misconduct records from the Town of Manlius Police Department and was told to pay $47,504 to see them.

Beryl Lipton, former projects editor at MuckRock said, “In New York the police unions have done solid work of trying combat the release of materials, with many agencies refusing to release records while those court battles played out; still others have claimed that the law does not apply retroactively to existing records, and the courts have landed on either side of that point.”

Last April, state Supreme Court Justice Ann Marie Taddeo issued an order agreeing with the Brighton Police Patrolman Association that the repeal of Section 50-a was not retroactive.

Then in May the Onondaga County Supreme Court ruled that the Syracuse Police Department’s could limit the misconduct records it released to those where charges were sustained – closing most records. The New York Civil Liberties Union appealed that decision last month.

On Long Island, Nassau and Suffolk County police departments have refused to turn over complaints that were not sustained and Nassau redacted much of the information it turned over to Newsday. Newsday is suing.

The New York Police Department also has limited the release of misconduct information to sustained cases and the New York Civil Liberties Union is suing the department.

Nationwide, the majority of law enforcement agencies still close records or make them hard to obtain. They claim they are personnel matters, privacy violations, or ongoing investigations that could be compromised. They are backed by strong law enforcement unions and the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights that protect the privacy rights of officers over the public’s right to know.

The National Decertification Index published by the International Association of Directors of Law Enforcement Standards and Training compiles 30,257 decertifications from 45 state agencies, but the names are closed to the public.

Sam Stecklow, a journalist with the Invisible Institute — a nonprofit journalistic group focused on public accountability — said it has become easier to request records in Illinois and New York. Nebraska, Hawaii, Kansas and Virginia are closed to the public.

“There are some states that we haven’t even been able to work at all in because they … require you to be a resident to make a request,” Stecklow said. “So we just haven’t really tried there. That includes Tennessee and Delaware and Virginia as well.”

Stecklow said many more states release the names of officers only in the rare instances when complaints are sustained. Much more frequently, the department decides not to punish the officer.

“I think it’s important to make a distinction regarding sustained versus not sustained cases,” Stecklow said. “Many states will allow the release of records about a case in which discipline is imposed, but that is a very small minority of police misconduct investigations.”

Stecklow said if state legislatures wanted to settle the question of requesting misconduct records, they could easily do so.

“They could very easily amend the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and explicitly say you know a record that either contains an allegation of police misconduct, or an investigation into an allegation of police misconduct or a disciplinary record regarding misconduct is always public,” Stecklow said.

In Florida, one state that has been known for keeping records of police misconduct open, two officers who shot and killed suspects in Tallahassee recently won court decisions to keep their names secret. They argued they should be protected by a new “Marsy’s law” that withholds the names of victims of crimes. The officers successfully argued that the men they had killed had threatened them and for that reason they were crime victims.

Virginia Hamrick, a lawyer for the First Amendment Foundation of Florida, said, “It just allows law enforcement officers to go around without any accountability. And it just makes it harder for public oversight of policing and specifically deadly force.”

Nineteen states have open or mostly open police misconduct records. Thirty-two states, including the District of Columbia, have closed or restrictive laws that keep most police misconduct secret. This nationwide roundup is based on an analysis of statutes and court opinions as well as interviews with experts. To stay up to date with the rapidly changing laws, visit the bill tracking database of the National Conference of State Legislatures.

ALABAMA: RESTRICTED

Police disciplinary records are available to the public, but agencies can require that requesters state the reason for their request.

A 1995 opinion by then Alabama Attorney General Jeff Sessions opened the door to agencies withholding documents, said Sam Stecklow, a journalist with the Invisible Institute, a nonprofit journalistic group focused on public accountability.

Under the opinion, agencies can deny requests because the release of the records “could reasonably be expected to be detrimental to the public safety or welfare, and records the disclosure of which would otherwise be detrimental to the best interests of the public.” Stecklow also points out that the law does not address release of misconduct records where there is no punishment.

Alabama enacted a law this spring to create a statewide database of police misconduct to help police departments avoid hiring officers with problems. But the law closes the database to the public. The legislature also failed to fund creation or maintenance of the database.

A recent Alabama Supreme Court decision closed access to investigatory files of police criminal investigations, and it also could have an impact on internal investigations of officers.

ALASKA: MOSTLY CLOSED

Police misconduct records in Alaska are generally not available because state employees’ personnel and disciplinary records are exempted from the Alaska Public Records Act (A.S. 39.25.080). There is also no database that tracks shootings or use of force in the state.

The Alaska Supreme Court ruled last year that disciplinary records for Alaska State Troopers are confidential. Alaska has come under fire from local media organizations and the Reporter’s Committee for Freedom of the Press for this exception.

When a police department fires or disciplines an officer for serious misconduct, it must report the discipline to the Alaska Police Standards Council. If the disciplined officer does not contest the action, the information is confidential. If the officer contests the action, there is a public hearing process.

Dozens of police officers with criminal records have worked in Alaska’s cities, despite a state law that should have disqualified them, an investigation by the Anchorage Daily News and ProPublica found. One of these officers was Nimeron Mike, a registered sex offender who spent six years in prison and was convicted of assault, domestic violence and other crimes.

ARIZONA: MOSTLY OPEN

Police misconduct records are generally available to the public as long as any investigation concerning the misbehavior has been completed, according to Arizona Statute 39-128. Local Arizona TV station ABC15 compiled “Brady lists” from all the counties: lists of officers not considered honest enough to testify in court. The lists totaled 1,400 officers. The station found that prosecutors often failed to disclose that an officer was on the list.

The Arizona House passed a bill this year, supported by the Phoenix Law Enforcement Association, that would have closed the list. It hasn’t passed the Senate.

Another investigation conducted by the Arizona Republic discovered that Phoenix police frequently purge officers’ records to keep police misconduct a secret.

Arizona also provides an “integrity bulletin” to the National Decertification Index on the International Association of Directors of Law Enforcement Standards and Training’s website but it doesn’t disclose the names of officers disciplined in the bulletin. Arizona is one of 11 states that provide this public bulletin.

ARKANSAS: RESTRICTED

Police misconduct records are not available to the public unless one can prove a compelling public interest, and they deal with an officer’s official suspension or termination. Personnel records are not eligible to be requested to the extent that disclosure would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy, according to Arkansas Code § 25-19-105. Only records relating to proven misconduct are released.

CALIFORNIA: MOSTLY OPEN

In 2018 the state’s legislature passed SB 1421, The Right To Know Act, which grants access to certain instances of excessive use of force, any incident where an officer fires a gun at a person and records relating to sexual misconduct. Before this, most law enforcement misconduct records were closed and typically could not be obtained by the public or the court system for criminal proceedings.

The legislature expanded on the 2018 law by passing SB 16 in the fall of 2021, opening records of sustained findings of use of excessive force, failure to intervene when other officers use excessive force, engaging in racist or biased behavior and conducting illegal searches or stops.

Instances where the public can access police misconduct records under 1421 include:

● An incident regarding the discharge of a firearm.

● An incident in which use of force by an officer resulted in death or serious injury.

● An incident in which a sustained finding was made by any law enforcement agency or oversight agency that a peace officer or custodial officer engaged in sexual assault involving a member of the public.

● An incident in which a sustained finding was made by any law enforcement agency or oversight agency of dishonesty by a peace officer or custodial officer directly relating to the reporting, investigation or prosecution of a crime; or directly relating to the reporting of, or investigation of misconduct by, another peace officer or custodial officer, including but not limited to, any sustained finding of perjury, false statements, filing false reports, destruction, falsifying or concealing of evidence.

(See more: ACLU Access to CA Police Records).

COLORADO: MOSTLY OPEN

A law passed in Colorado in 2019 — HB 19-1119 — opens some police misconduct records that hadn’t previously been opened, but the narrow wording restricts its effectiveness.

Stecklow points out the new law initially was limited because “it is not retroactive and has language that currently requires requesters to know of specific instances of misconduct, rather than allowing requests for records in general.”

The law opened records “related to a specific, identifiable incident of alleged misconduct involving a member of the public” while the officer is on duty. Denver and Aurora have made misconduct files available but many other departments have not, claiming requests are too vague, says Jeffrey A. Roberts, executive director of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition.

But a Colorado Supreme Court ruling in June, 2021, gave the law a broader interpretation, holding that people seeking information did not have to identify a particular incident.

Colorado also is developing procedures to make public the names of police officers on so-called “Brady” lists because of past failures to disclose exculpatory evidence to defendants. But the attorney general has refused to disclose decertification data on problem officers.

Additional police conduct information will be made public under Senate Bill 20-2017, the state’s criminal justice reform bill, which goes into full effect in 2023.

Agencies will be required to release unedited audio and video footage from body and dash cameras of any incident where misconduct is alleged.

“Other transparency provisions in the bill include the public reporting, in an online searchable database, of extensive information on use of force by law enforcement officers that results in death or serious injuries, and the reporting of interactions between officers and the public,” according to the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition.

CONNECTICUT: MOSTLY OPEN

Police misconduct records in Connecticut are generally public because of the precedent set by the state Supreme Court in 1993 in Perkins v. Freedom of Information Commission, which stated records could be withheld only if they did not pertain to matters of public concern. However a new contract with state troopers limits the access to misconduct records by only making them accessible if a complaint is sustained. Most complaints are not sustained.

According to a study compiled by the ACLU of Connecticut, many departments make it difficult to file a misconduct complaint against an officer. Forty-two percent of the departments in the state surveyed by the ACLU suggested they are not complying with state law requiring public access to complaint policies.

Connecticut is one of 11 states that provide an integrity bulletin to the National Decertification Index, which makes the names of these officers public.

However, this integrity bulletin doesn’t provide 100% transparency and an investigation by the ACLU of Connecticut found that none of the prosecutors had “Brady lists” of dishonest cops.

WASHINGTON, D.C.: CLOSED

Police misconduct records are mostly closed in Washington, but activists, including the DC Open Government Coalition, are pushing for reform.

The Washington City Paper reports that the district government regularly invokes the “personal privacy” exemptions in Section 2-534(a)(2) of the D.C. Freedom of Information Act. Strong police unions advocate keeping the records private.

DELAWARE: CLOSED

Police misconduct records are closed and exempt from public disclosure in Delaware by both the Delaware Freedom of Information Act and under Section 12 of the state’s Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights. A bill that would open more records is pending in the legislature.

According to the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, law enforcement organizations in Delaware are sometimes willing to provide general statistics but are usually unwilling to provide specific records in response to information requests.

“Fifteen states have versions of a Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights (LEOBOR) statute, but only Delaware’s statute makes internal police investigation records completely confidential forever,” said the ACLU of Delaware.

FLORIDA: MOSTLY OPEN

Law enforcement misconduct records in Florida are generally available under the state’s Freedom of Information Act/Sunshine laws (Florida Statute 119) if the investigation is closed. All active investigations are exempt from public information requests until they are closed or completed.

Misconduct records in Florida are sent to a database that is maintained by the state’s Criminal Justice Standards and Training Commission and this is open for public inspection.

Florida is one of 11 states that provides an integrity bulletin to the National Decertification Index. It bulletin lists offending officers’ names are public.

A law passed by voters in 2018 could remove the names of some police officers from reports on police shootings. “Marsy’s law” allows victims of crimes and threats to have their names removed police reports. Two police officers who shot and killed suspects have won court orders to remove their names from public reports because their dead suspects had threatened them before the officers killed them.

GEORGIA: MOSTLY OPEN

Under the Georgia Open Records Act, law enforcement misconduct records are available to the public unless the investigation into the misconduct is active and ongoing.

HAWAII: RESTRICTED

After years of closing records on police misconduct, a new law amending Hawaii’s public record laws passed the state legislature in July 2020. But it allows disciplinary records older than 30 months to be destroyed and denies the release of some misconduct complaints when there is lesser or no discipline.

The new law requires county police departments to disclose to the Legislature the identity of an officer who is suspended or discharged and requires law enforcement departments to provide a yearly update regarding misconduct. It also allows public access to information about suspended officers.

A September, 2021 decision of the Hawaii Supreme Court required the release of an arbitration decision that a Honolulu police sergeant had tried to keep from the public. Restaurant video had captured Sgt. Darren Cachola in a physical altercation with a woman. Sergeant Cachola was fired, but reinstated with back pay after taking the case to arbitration. The Civil Beat newspaper filed a request for the arbitration decision. The high court ruled the arbitration record had to be made public because the public interest outweighed the officer’s privacy interests.

The most detailed versions of the disciplinary records of the Honolulu Police Department are destroyed after 30 months, says R. Brian Black, executive director for the Civil Beat Law Center for Public Interest. “The department does get rid of its more detailed disciplinary documents after 30 months, but it retains a notecard in the file with a summary sentence about the discipline and the nature of the misconduct.”

For lesser punishments — those below firing and suspension — the 2020 law balances privacy against the public interest. Privacy considerations often prevail and close records.

IDAHO: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement misconduct records are closed under Idaho’s Freedom of Information Act, according to Section 74-106 of the Idaho Public Records Act. Idaho police departments also routinely ignore a 1996 court decision that made “administrative reviews” of police shootings public.

ILLINOIS: MOSTLY OPEN

Most law enforcement misconduct records in Illinois are available because of the precedent set in 2014 with Kalven v. City of Chicago.

Law enforcement agencies in Illinois must provide a “misconduct registry” detailing general information about what an officer was cited for.

In June 2020, in City of Chicago v. Fraternal Order of Police Chicago Lodge No. 7, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that misconduct records must be preserved and cannot be destroyed every five years, as the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police advocated.

There is a Professional Conduct Database maintained by the state board responsible for certifying and decertifying officers. Local police departments must report to the database when an officer resigns, is fired or is suspended for violating department policy. However, a police reform law passed this year closes the database, including supporting documents. To get statewide records, a person would have to contact each of the hundreds of police departments.

INDIANA: RESTRICTED

The Indiana Legislature passed a bipartisan police reform law this spring, signed by Gov. Eric Holcomb, that provides publication of the names of decertified officers on the website of the Indiana Law Enforcement Academy. But Stecklow says the law allows police agencies to close cases where there was no discipline.

Stecklow says “there is a lot of inconsistency. Some agencies claim an ‘investigative records’ provision in the records law allows them to withhold misconduct records, but there have been rulings that the investigative records exception only applies to criminal records. Still other agencies deny the records saying they are ‘deliberative records.’”

The Indiana Law Enforcement Training Board has revoked 45 licenses since 2007, with only five in the past two years.

Indiana is one of 11 states, providing an integrity bulletin to the National Decertification Index. Those bulletins disclose the names of the officers disciplined.

IOWA: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement records in Iowa are closed except where officers were fired, according to Iowa Code § 22-7-11.

However, even when records should be public under Iowa’s law, law enforcement agencies can find ways to deny them. Newspapers have taken cases to the Iowa Supreme Court because agencies have refused to turn over names and records relevant to the public.

KANSAS: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement misconduct records are closed under the Kansas Open Records Act (Kansas Statute 45-221). Kansas Senate Bill 270 would make certain law enforcement disciplinary/misconduct records available to the public and prevent the hiring of officers with a history of serious misconduct allegations. It is still in the state’s Senate Judiciary Committee.

Kansas is one of 11 states that provides an integrity bulletin to the National Decertification Index, but it does not disclose the names of officers disciplined.

The Kansas City Star has been fighting these exemptions to obtain records from the Overland Park severance agreement with former officer Clayton Jennison, who shot a 17-year-old to death in 2018 while making a “welfare check” on the youth.

KENTUCKY: MOSTLY OPEN

Access to police misconduct records through the Kentucky Open Records Act is limited and up to the discretion of the law enforcement agencies or departments involved.

Departments can use KRS § 61.878(1)(a) to claim a general exemption for the records because of privacy concerns for the employee or officer. However, the Kentucky Attorney General has ruled that for the most part, misconduct records should be made public, as in the Linda Toler v. City of Muldraugh case of 2004 (03-ORD-213).

More recently, in March of this year, the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled that the University of Kentucky had to turn over records of a sexual harassment investigation it had conducted of a professor who was allowed to resign without a final determination of his conduct. The Supreme Court ruled that “where the disclosure of certain information about private citizens sheds significant light on an agency’s conduct, we have held that the citizen’s privacy interest must yield.”

An investigation by the Louisville Courier-Journal uncovered that police concealed and lied about as many as 750,000 documents in an investigation of sexual misconduct by officers in the Explorer Scout program, where police were abusing minors. The Courier-Journal sued to uncover these records, and a small portion was released. The FBI has since opened an investigation into the Explorer program.

LOUISIANA: MOSTLY OPEN

Law enforcement misconduct records are generally public and are not an exception to the Louisiana Sunshine laws, but some departments may try to deny them based on the state’s privacy protections. In one such case, the city of Baton Rouge tried to deny records to the Capital City Press and the paper appealed the decision.

While misconduct records in Louisiana are mostly public, an investigation by the Southern Poverty Law Center found serious gaps in the collection of other police data by law enforcement agencies, including data dealing with racial profiling.

MAINE: RESTRICTED

Law enforcement misconduct records in Maine are available to the public if an investigation is completed or closed. However, investigations that don’t result in discipline or that have findings that are not sustained are not made available to the public.

An investigation conducted by the Bangor Daily News and the Pulitzer Center found that these records often hide misconduct and lack transparency by not fully describing the incidents in question. Maine only requires that the final findings of an investigation be public, not the internal investigations leading up to a disciplinary decision.

One example cited by the Bangor Daily News is the case of Matthew Shiers, whose public records show that he was fired. They exclude the fact that the internal investigation was prompted by charges against him of aggravated assault, domestic violence and cruelty to animals after fighting with his girlfriend.

MARYLAND: MOSTLY OPEN

In April 2021 the state’s House and Senate passed Anton’s Law, which will expand access to police misconduct records and increase the use of body cameras in the state. Previously, law enforcement investigations and misconduct records were sealed to the public in Maryland. The law, passed despite the governor’s veto, also repealed the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights.

The public will now have access to misconduct records.

Since passage of the law, some Maryland law enforcement agencies have tried to get around it by withholding the names of officers or by charging large record reproduction fees.

MASSACHUSETTS: MOSTLY OPEN

A new law opens law enforcement misconduct records in Massachusetts, where they had previously been mostly closed. Even before the new law some police records had been released under a court opinion stating that internal affairs investigative records were not the kind personnel records that could be withheld from disclosure.

MICHIGAN: RESTRICTED

Police misconduct records are not explicitly secret in Michigan. However they are often denied and considered an unwarranted invasion of privacy under the state’s Freedom of Information Act, Section 15.243.1(a).

Michigan’s Attorney General Dana Nessel called for the creation of a database that would track police misconduct statewide through the Michigan Commission on Law Enforcement Standards.

The database has not been created.

MINNESOTA: RESTRICTED

Some law enforcement misconduct records are open to the public under Minnesota’s public record laws. But the law limits disclosure to those cases that go to discipline.

Minnesota is one of 11 states, providing an integrity bulletin to the National Decertification Index. Those bulletins disclose the names of the officers disciplined..

MISSISSIPPI: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement misconduct records are closed and inaccessible to the public.

MISSOURI: MOSTLY CLOSED

On the last day of the session on May 14, 2021, the Missouri Legislature adopted and sent to the governor Senate Bill 26,which closes misconduct records and adopts a Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights, making it hard to discipline officers. The bill, expected to be signed by the governor, states that the full administrative record of an investigation into misconduct “shall be confidential and not subject to disclosure under Sunshine Law, except by lawful subpoena or court order.”

The bill also requires local law enforcement to report use of force data to the federal government but redacts the officers’ names by stating, “the personally identifying information of individual peace officers shall not be included in the reports.”

Law enforcement misconduct is usually kept secret in Missouri, but in 2015, a Missouri court ordered the release of police misconduct records relating to police abuse of World Series tickets in Chasnoff v. St. Louis Board of Police Commissioners. The court said police had no right to privacy of these records. Stecklow explains, “The Chasnoff decision hinged on whether the allegations being investigated could have a criminal element or not; if yes, the records should be released.”

The state’s POST Commission does not disclose the names of officers who were decertified, although it responds to requests for information, Stecklow says. Information also becomes public if an officer contests decertification and appeals to a hearing board.

MONTANA: RESTRICTED

In the past, police misconduct records in cases that went to discipline were generally public, but a state supreme court opinion states that even in cases going to discipline an officer may have a privacy interest that justifies keeping the record closed.

Montana Code § 2-6-102 and Article II, Section 10 of the Montana Constitution lay out a right of privacy. The phrasing is as follows: “The right of individual privacy is essential to the well-being of a free society and shall not be infringed without the showing of a compelling state interest.” This allows police departments to argue that most public disclosures of police records do not have a good enough public benefit to justify harming an officer’s individual privacy. However, in some cases, judges have ruled in favor of records being disclosed under Section 9 of the Montana Constitution.

Montana is one of 11 states that provide an Integrity Bulletin to the National Decertification Index, but the bulletins do not disclose the names of officers decertified.

NEBRASKA: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement misconduct records are secret in Nebraska.

A proposed bill that was introduced in the state’s Legislature Jan. 20, 2021, would create a police misconduct database, but it has yet to be voted on.

NEVADA: RESTRICTED

Law enforcement misconduct records are restricted in Nevada and it is up to the discretion of individual law enforcement agencies if they are disclosed.

NEW HAMPSHIRE: RESTRICTED

Law enforcement misconduct records historically were closed in New Hampshire under a personnel exemption to public record requests, but a series of state court decisions limited the use of the personnel exemption in the state Right to Know law. The personnel exemption had been used to keep police misconduct records closed.

A pending state supreme court case is being closely watched to see if the court will require the Canaan Police Department to turn over an investigation of Officer Sam Provenza, who is alleged to have pulled a woman out of her car by her hair during a traffic stop and injured her leg.

A compromise law passed by the legislature in 2021 provides for the gradual release of Laurie’s List of 270 officers who have been accused of dishonesty. Before those officers’ names are released, each has a chance to go to court to challenge placement on the list. Names are expected to begin to be released in late 2021.

NEW JERSEY: RESTRICTED

Law enforcement misconduct records have historically been closed in New Jersey, but the attorney general won a court decision last year that would open records of officers who faced discipline for the most serious misconduct. A pending bill would open more records.

NEW MEXICO: RESTRICTED

Police departments have routinely used New Mexico Statute 14-2-1 (A)(3) to withhold records from the public. The statute states that some records are matters of opinion and not subject to public release. It closes “letters or memorandums, which are matters of opinion in personnel files.” A 1970s state supreme court decision held that “disciplinary action” and other “matters of opinion” could be withheld. But a 2009 state attorney general’s opinion and a 2010 state court decision Cox v. New Mexico Department of Public Safety found that citizen complaints against officers should generally be open, even if the department’s disposition of those complaints were closed as matters of opinion.

NEW YORK: MOSTLY OPEN

Law enforcement misconduct records became public in New York in August 2020 following nationwide protests after the death of George Floyd at the hands of police.

New York’s police unions strongly opposed this change and five of them united and sued the state when it passed.

(See more: CPR’S INTERVENTION MOTION IN NYPD MISCONDUCT DATABASE CASE.)

They were unsuccessful in preventing the release of records and a database revealed more than three decades of complaints.

Police departments across the state — from Nassau and Suffolk counties on Long Island, to New York City, to Syracuse and Brighton have spent the past 18 months limiting disclosures. They argue that only substantiated complaints are open, leaving out the much greater number of unsubstantiated complaints. The Town of Manlius Police Department attempted to charge the nonprofit organization MuckRock the prohibitive price of $47,504 to access their records.

NORTH CAROLINA: MOSTLY OPEN

Law enforcement misconduct records are kept secret in North Carolina. If an officer is dismissed, demoted or suspended, the disciplinary action and date are publicly available but not the reason. (North Carolina G.S. § 153A-98 and § 160A-168.) A pending bill would open more records.

NORTH DAKOTA: MOSTLY OPEN

Law enforcement misconduct records are available to the public in North Dakota.

OHIO: MOSTLY OPEN

Law enforcement misconduct records are available to the public in Ohio.

OKLAHOMA: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement records can only be publicly accessed if they involve an officer losing pay or being suspended, demoted or terminated. (Title 51, Oklahoma Statute §24A.8.)

OREGON: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement misconduct records are mostly closed in Oregon and are often denied if there was no discipline involved, according to Stecklow.

Decertified police officers in Oregon are tracked in a statewide online database maintained by the agency responsible for law enforcement certification. This database was created during a special legislative session in 2020 that called for more police accountability. Oregon does release the names of officers who have been decertified in the state. It began doing this after the death of George Floyd in 2020.

Oregon is one of 11 states that provide an integrity bulletin to the National Decertification Index, but it doesn’t disclose the names of officers disciplined.

PENNSYLVANIA: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement misconduct records are mostly closed in Pennsylvania and their release is up to the discretion of the law enforcement agency, according to Stecklow.

Under the state’s Right to Know Act, the following are secret and exempt from public record requests: a performance rating or review; all documents relating to written criticisms of an employee; grievance material; documents related to discrimination or sexual harassment; information regarding discipline, demotion or discharge contained in a personnel file; arbitration transcripts and opinions; most complaints of potential criminal conduct; and investigative materials, notes, correspondence, videos and reports. (Section 67.708(b) of Pennsylvania’s Right-to-Know Law.)

If an officer is discharged or demoted, this will be made public, but not the reason for the disciplinary action.

In 2020 Gov. Tom Wolf signed a bill into law that created a database to track police misconduct statewide and force agencies to check the database before hiring an officer. Like Illinois, this database is confidential and off limits to the public.

RHODE ISLAND: MOSTLY CLOSED

Attorney generals’ opinions apply a balancing test that weighs the public interest against an officer’s privacy interest. If a document can be released in redacted form without violating privacy interests it will sometimes order the release. In a case this year, the attorney general’s opinion ordered the release of 14 of 17 documents requested, but in redacted form.

SOUTH CAROLINA: MOSTLY OPEN

The public has restricted access to law enforcement misconduct records in South Carolina.

South Carolina police departments have kept records from being released based on South Carolina Statute 30-4-40, which states the release of certain information is a violation of officers’ privacy. This was pushed back against in Burton v. York County Sheriff’s Department, which said that public interest often outweighs privacy interest in police officer cases. In certain instances, records can be released with the personal identifying information of the officer involved redacted.

SOUTH DAKOTA: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement misconduct records are kept secret in South Dakota.

TENNESSEE: MOSTLY OPEN

Law enforcement misconduct records are fairly accessible, according to the Tennessee Code. In certain cases however, such as Contemporary Media v. Gilless, departments have been able to hold records by arguing that they were part of ongoing or recent criminal investigations. If personal information of an officer is included in requested reports, the officer must be notified.

However, an investigation by WREG in Memphis found that some departments are using an outdated, paper-based system that makes it nearly impossible to receive the requested data, or charges the requester excessive fees.

According to the WREG investigation as of July 2020: “In January, WREG asked for records of excessive force and firearm discharge from 2015 to 2019. We were told that would cost nearly $7,500 because there were 24,000 pages of documents and it would take 88 hours to retrieve and redact information. On Feb. 6, we narrowed the timeline to just six months. Now almost six months later, we’re still waiting.”

TEXAS: RESTRICTED, DEPENDING ON CITY

According to research conducted by WNYC radio, “Texas Government Code § 552 generally renders police disciplinary records public. However, many cities in Texas are also covered by Local Government Code § 143, which requires police departments to maintain civil service personnel files on each police officer. Those civil service files are available for public inspection and contain records of disciplinary actions, but only if the officer received at least a suspension or loss of pay. If the only discipline was a ‘written reprimand,’ the records are instead placed in a confidential internal file.”

UTAH: RESTRICTED

Law enforcement records are public in Utah, unless their release would interfere with an active investigation.

Utah is one of 11 states that provide an integrity bulletin to the National Decertification Index, but it doesn’t disclose the names of the officers disciplined in this bulletin.

“Only cases that result in discipline are always public,” Stecklow said. “The rest are subject to a balancing test weighing privacy and public interests, and which can often come down on the side of privacy.”

VERMONT: RESTRICTED

Vermont keeps the names of officers about whom complaints are filed a secret unless a state board decides to impose discipline, in which case the names and details are public.

Records containing the names of officers who engaged in misconduct should be released if public interest outweighs the privacy interest of the officer, the state courts ruled in Rutland Herald v. City of Rutland. In this case the court ordered the release of the names of officers who had viewed pornography on departmental computers.

Vermont is one of 11 states that provide an integrity bulletin to the National Decertification Index, and it makes the names of these officers public.

VIRGINIA: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement misconduct records are kept secret in Virginia. (Section 2.2-3705.1 of the Virginia Freedom of Information Act.)

A pending bill would open up most records in Virginia.

WASHINGTON: MOSTLY OPEN

Law enforcement misconduct records are available to the public in Washington.

Washington is one of 11 states that provide an integrity bulletin to the National Decertification Index, and it makes the names of decertified officers public.

WEST VIRGINIA: RESTRICTED

Similar to Vermont and South Carolina, police departments can withhold records if they would be against privacy interests (Freedom of Information, Statute 29B 1-4, Exemptions), but often courts will rule that public interest outweighs the privacy interests of officers.

Charleston Gazette v. Smithers set the precedent that conduct of police officers while they are on the job is public record. This rule is now in the West Virginia Code 29B.

WISCONSIN: MOSTLY OPEN

Law enforcement records are generally available to the public in Wisconsin. Wisconsin Statute § 19.36(10)(b).

A pending bill would open most of the records.

WYOMING: MOSTLY CLOSED

Law enforcement misconduct records are kept secret and hidden from the public in Wyoming.

Kallie Cox is the editor-in-chief of The Daily Egyptian, the student newspaper of Southern Illinois University Carbondale and can be reached at Kcox@dailyegyptian.com or on Twitter @KallieECox. William H. Freivogel is a professor at Southern Illinois University and a member of the Missouri Bar. Zora Raglow-DeFranco, a law student at Case Western, contributed to this report.