When the great-grandmothers of today’s young women were born, women couldn’t vote. They were expected to be mothers and homemakers.

When the grandmothers of today’s young women were born, women had no legal protections against discrimination in education, jobs or credit. The Supreme Court said “Equal Protection” in the 14th Amendment didn’t include women.

When the mothers of today’s young women were born, the nation was in the midst of a great legal and social revolution so sweeping that women began to take their places as equals in society and before the law. They had gained control of their reproductive decisions and legal protection against pregnancy discrimination, sexual harassment and discrimination in education programs. Female teachers couldn’t be fired any longer for getting pregnant and girls’ and women’s sports teams started getting more resources.

Today’s young women are coming of age at a time when their legal rights are being cut back for the first time in this century-long continuum of growing autonomy and expanding women’s rights as the Supreme Court has taken away a woman’s control of her reproductive decisions.

The Founding Fathers would not be surprised that the law would limit women’s rights; they recognized no women’s rights.

Abigail Adams, wife of one president and mother of another, took time out from managing the family farm and household in Braintree, Mass. to write a letter to her absent husband on March 31, 1776. She wrote: “…in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies…We are determined to foment a Rebellion and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.”

Historians say she was mostly kidding and that’s certainly the way her husband took it in his reply talking about the “Despotism of the Petticoat.”

Coverture and subservience

The subservient status of colonial women is shocking today, but it was accepted without question by the Framers of the Constitution who didn’t even debate it at the Constitutional Convention.

“Most Americans for much of their history were convinced that God and nature had decreed that the two sexes inhabit different spheres and have different roles,” said historians Linda K. Kerber and Jan Hart-Matthews. “Men’s roles were public and political, women’s domestic.”

Through the entire 19th century and into the 20th, women’s intellectual pursuits were widely believed to be improper, physically harmful and detrimental to motherhood and perpetuation of the race.

Thomas Jefferson hoped women would be “contented to soothe and calm the minds of their husbands returning ruffled from political debate.” As president, he quickly put an end to a rumor he might appoint women to political office – “an innovation for which the public is not prepared, nor am I,” he said.

In antebellum days, the progressive ideal of a woman was defined by Republican Motherhood, influencing their husbands and educating their sons for public service. The ideal Republican Mother was rational, self-reliant and benevolent.

At this time, the rules of coverture – derived from English common law – gave husbands the rights to a wife’s paid and unpaid labor, most of her property and her obedience. Wives couldn’t sue or make contracts without their husbands’ consent, nor could they vote. In the eyes of the law, the “very being or legal existence of the women is suspended during marriage” wrote William Blackstone, the great 18th-century legal commentator from Britain.

In 1839, Mississippi enacted the first Married Women’s Property Act, but it was mainly intended to give women continued control of slaves.

Catharine Beecher traveled the country campaigning for a schoolhouse in every community and a woman in every schoolhouse. Male teachers, she noted, were often “low, vulgar, obscene, intemperate” and bad teachers.

When women gathered at Seneca Falls in 1848, they wrote their Declaration of Sentiments, patterned on the Declaration of Independence, except they declared “all men and women are created equal.” Instead of laying out King George’s tyrannies, it laid out the tyrannies of men, beginning with the refusal to allow women to vote or have any voice in lawmaking. Other grievances were discrimination in education, jobs and pay and the prevailing double standard of morality.

Man “has endeavored, in every way that he could, to destroy woman’s confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who wrote the declaration, hadn’t always believed in a public role for women. She and her husband attended a convention in London to discuss abolition of slavery. The men at the convention debated whether women should be allowed to join them, while the women sat in a curtained gallery and were forbidden to speak on the question. “Refined torture,” Stanton called it.

That is where she met Quaker preacher Lucretia Mott from Philadelphia and was astonished to see her speak to a group of men. The two decided to hold a women’s convention in the U.S., which became Seneca Falls. In the meantime, Stanton had been chafing at her husband’s patronizing attitudes.

“How rebellious it makes me feel when I see Henry going about where and how he pleases,” she complained in a letter. “He can walk at will through the whole wide world or shut himself up alone. As I contrast his freedom with my bondage I feel that, because of the false position of women, I have been compelled to hold all my noblest aspirations in abeyance in order to be a wife, a mother, a nurse, a cook, a household drudge.”

Despite the bold words in the proclamation, none of the women at Seneca Falls was bold enough to be chairman; instead, they asked Mott’s husband to serve as chair. Also, the call for suffrage for women passed by a bare majority.

The press roundly denounced the Seneca Falls declaration. Some papers called the women “Amazons.” Others criticized those seeking a “petticoat empire.” The Albany Advocate wrote, the Declaration of Sentiments was a mere parody and added, “it requires no argument to prove that this is all wrong. Every true hearted female will instantly feel that this is unwomanly.”

“Equal” doesn’t apply to women

The 14th Amendment provided in 1868 that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States” and added, “No State shall…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

But when two women – one from Missouri and one from Illinois – went to the Supreme Court to claim the amendment’s protection, they quickly found they were not included.

Myra Bradwell had studied law in her husband’s Chicago law office and ran a well-respected legal publication. The Illinois Supreme Court had denied her the right to practice law solely because she was a woman. She argued the privileges and immunities protected by the 14th Amendment included her right to pursue a profession.

Her lawyer in the Supreme Court, Matthew Hale Carpenter, harkened back to the Declaration of Independence saying, “In the pursuit of happiness all vocations, all honors, all positions, are alike open to every one; in protection of these rights all are equal before the law.”

There was no lawyer arguing the other side of the case, but Bradwell lost anyway. As the 1873 opinion put it, “the civil law, as well as nature herself, has always recognized a wide difference in the respective spheres and destinies of man and woman. Man is, or should be, woman’s protector and defender. The natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life.”

“The harmony…(of) the family institution is repugnant to the idea of a woman adopting to a distinct and independent career from that of her husband…The paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfill the noble and benign offices of wife and mothers. This is the law of the Creator.”

Practicing law is a right that can be granted by a state, not a privilege guaranteed by the Constitution, the court said.

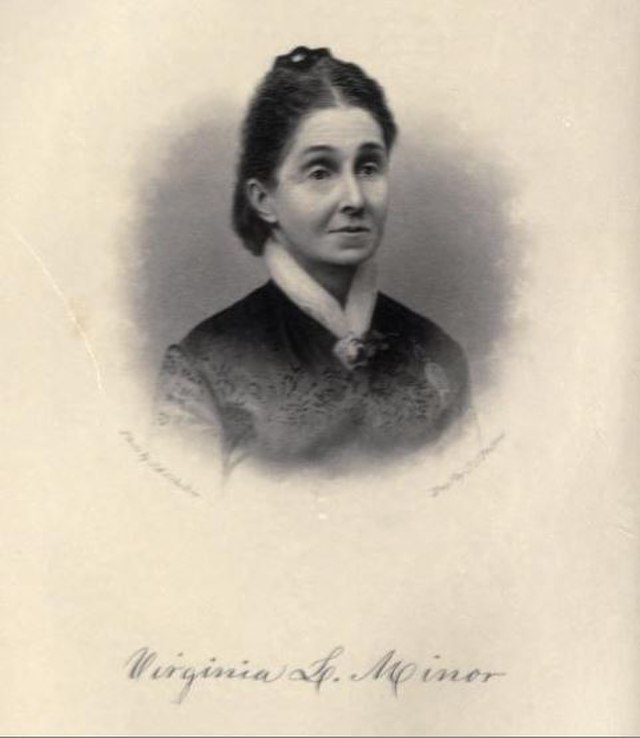

The next year, the Supreme Court turned away Virginia Minor, the president of the Women’s Suffrage Association of Missouri, who had tried to register to vote in St. Louis in 1872 but been denied by the registrar.

Chief Justice Morrison Waite, writing for a unanimous court, wrote there was no doubt but that women may be citizens, but there was also no doubt that not all citizens of the United States can vote. It’s up to the states to decide who has that right and Missouri said no.

“If the law is wrong it ought to be changed,” the court said. “But the power for that is not with us.”

Also after the Civil War, Anthony Comstock crusaded successfully for the passage of laws against pornography that included provisions Comstock himself had drafted making contraception illegal. Soon 24 states had passed laws outlawing contraceptives. Comstock believed that contraception caused lust and lewdness.

Woman not made for man

At the nation’s centennial in 1876, women suffragists asked for permission to hold a silent protest at the reading of the Declaration of Independence. They were turned away, told the nation was celebrating “what we have done the last hundred years, not what we have failed to do.”

Susan B. Anthony and four women showed up anyway and set up their counter-centennial speech across the street from Independence Hall. “We ask our rulers, at this hour, no special privileges, no special legislation. We ask justice, we ask equality, we ask that all the civil and political rights that belong to citizens of the United States be guaranteed to us and our daughters forever…We deny that dogma of the centuries, incorporated in the codes of all nations – that woman was made for man – her best interests, in all cases, to be sacrificed to his will.”

Political Motherhood replaced Republican Motherhood. The extensive involvement of women in public life was justified as a kind of civic housekeeping and an extension of concern for children and families. Women joined the Women’s Christian Temperance Movement, the settlement house movement and National Consumers’ League.

Even when the Supreme Court seemed to be ruling in favor of women, it did so based on debilitating sex stereotypes. In 1908 in Muller v. Oregon, the court upheld Oregon’s imposition of a 10-hour work day for women. The court was persuaded to approve the law by a 113-page brief that Louis Brandeis – a future and famous justice – filed in its support.

But the decision was hardly a victory for women. It was an invitation to a permanent status of inequality and inferiority.

“That woman’s physical structure and the performance of maternal functions place her at a disadvantage in the struggle for subsistence is obvious,” wrote Justice David J. Brewer. “This is especially true when the burdens of motherhood are upon her…by abundance testimony of the medial fraternity continuance for a long time on her feet at work, repeating this from day to day, tends to injurious effects upon the body and as healthy mothers are essential to vigorous offspring, the well-being of woman becomes an object of public interest and care in order to preserve the strength and vigor of the race.

“Education was long denied her and while now the doors of the school room are opened and her opportunities for acquiring knowledge are great, yet even with that and the consequence in increasing the capacity for business affairs it is still true that in the struggle for subsistence she is not an equal competitor with her brother.

“Still again, history discloses the fact that woman has always been dependent upon man. He established his control at the outset by superior physical strength…As minors, though not to the same extent, she has been looked upon in the courts as needing especial care that her rights may be preserved.”

The 19th Amendment

Internal splits developed within the Suffrage Movement. Anthony and Stanton tried to win support from racist Democrats by arguing that white women should be allowed to vote to offset the new electoral power of Black men. Others found these arguments reprehensible and said they undermined the moral authority of the movement.

The movement was strong but splintered by 1916. One group, the National American Woman Suffrage Association, relied on careful tactics and ladylike behavior. Headed by Carrie Chapman Catt, the 2-million strong organization set up a powerful grassroots lobbying campaign by leading citizens.

Many of the more moderate women wanted to concentrate on building on the nine states that had recognized women’s suffrage by 1913.

Alice Paul organized the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession for March 3, the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Hostile counter-demonstrators overwhelmed an inadequate police presence, with male counter-demonstrators threatening some of the women.

After the march, Paul broke with the National American Woman Suffrage Association and formed the Congressional Union – later called the National Woman’s Party. It concentrated on pressuring President Woodrow Wilson to endorse a national constitutional amendment.

In January 1917, before Wilson’s second inauguration, Paul and other members of the National Woman’s Party picketed in front of the White House calling themselves “silent sentinels.” Picketing in front of the White House was unusual and possibly unprecedented.

Paul and some of the picketers were arrested and jailed. Eventually, Paul began a hunger strike to protest jail conditions and was force-fed raw eggs through a tube. The protests, arrests and hunger strike drew national attention but also generated angry attacks from bystanders who thought it disloyal and treasonous to picket the White House during a war.

In 1918, Wilson announced support for the amendment and the House passed it but it fell two votes shy in the Senate. Protests continued into 1919, with Wilson burned in effigy for not doing more to pass the amendment, which finally made it through the Senate.

In August 2020, Tennessee provided the decisive ratification vote. The vote was so close that it turned on the decision of the youngest member of the Legislature, Harry Burn. Burn said his mother had sent him a letter to “help Mrs. Catt.” He changed his mind and voted yes.

Alice Paul campaigned for women’s rights for four more decades, leading early advocacy of the Equal Rights Amendment and persuading Congress to add protection for women into the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Even ‘sprightly’ barmaids may not apply

Even after women won the right to vote, the Supreme Court continued to give women second class status under the Constitution.

As late as 1948, the court upheld a Michigan law that forbade a woman to work as a bartender unless she was the “wife or daughter of the male owner.”

Justice Felix Frankfurter jovially noted the “historic calling” of the “alewife sprightly and ribald,” but cautioned that the 14th Amendment “did not tear history up by the roots.” He added that Michigan could “beyond question, forbid all women from working behind a bar…The fact that women may not have achieved the virtues that men have long claimed as their prerogatives and now indulge in vices that men have long practiced, does not preclude the States from drawing a sharp line between the sexes.”

And in 1961, the court upheld a Florida law that excluded women from jury lists unless they requested inclusion, resulting in almost all all-male juries. The court continued to interpret equal protection in light of a woman’s role in the family, just as it had in Bradwell almost a century earlier. A woman, who had been convicted of killing her husband with a baseball bat after he cheated on her, thought women on the jury would better understand her plea of temporary insanity.

But the court said no. “Despite the enlightened emancipation of women from the restrictions and protections of bygone years, and their entry into many parts of community life formerly considered to be reserved to men, woman is still regarded as the center of home and family life.”

New laws

Major legal gains for women began with the Equal Pay Act of 1963. In 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act that included sex discrimination as an afterthought. A Southerner, Rep. Howard W. Smith, D-Va., helped add sex to the grounds for discrimination, possibly as a poison pill to defeat the entire act. Some members of Congress laughed. Smith joked the amendment would guarantee the right of every woman to a husband. Nevertheless, sex was included in the final law.

Another major victory for women and girls was Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which banned discrimination in education programs receiving federal funds.

Title IX is known best today for the enormous change brought in high school and college athletics. But it applies to all education programs receiving federal funds and has had a big impact on the investigation of sexual harassment on campuses.

Many of the early women’s rights cases involved discrimination against pregnant women.

In 1970, Jo Carol LaFleur, then 23, became pregnant while a teacher at Patrick Henry Junior High School in Cleveland. School board policy required pregnant teachers to take unpaid leave five months before birth. They could reapply for a position the school year after the baby turned three months but would be subject to a physical exam and wouldn’t get a job unless one was open. The schools said that pregnant women often couldn’t perform required duties during the last five months of pregnancy and that the policy was intended paternalistically to protect the health of the mother and baby.

LaFleur was forced to resign in March when her due date wasn’t until July. The Supreme Court, taking into account a brief filed by then attorney Ruth Bader Ginsburg, ruled in 1974 that the policy violated LaFleur’s liberty protected by the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment.

“Freedom of personal choice matters of marriage and family life is one of the liberties protected by the due process clause,” the court decided. After the experience, LaFleur, now Jo Carol Nesset-Sale, went to law school and became a lawyer.

But later the same year the court ruled against pregnant women in another case. It upheld a California insurance program that did not cover pregnancy and birth. The majority said the state could make distinctions based on pregnancy unless there were “mere pretexts designed to effect an invidious discrimination against members of one sex.” The court wrote in Gedulig v. Aiello that, “While it is true that only women can become pregnant, it does not follow that every legislative classification concerning pregnancy is a sex-based classification.”

Justice Samuel Alito in the Dobbs decision overruling Roe cites that case and concludes “regulation of abortion is not a sex-based classification” and therefore not subject to the close scrutiny that sex-based classifications would receive.

In 1976, the Supreme Court upheld a General Electric Co. disability plan that covered vasectomies and prostate surgery but not pregnancy. Justice William H. Rehnquist, wrote, “Exclusion of pregnancy from a disability benefits plan providing general coverage is not a gender-based discrimination at all.”

Justice William J. Brennan, the leading liberal on the court, thought this was nonsense. “Surely it offends common sense to suggest…that a classification revolving around pregnancy is not, at a minimum, strongly “sex related.’”

After the setbacks in the Supreme Court, women’s right groups persuaded Congress to pass the Pregnancy Discrimination Act in 1978 requiring employers with health insurance to provide coverage of pregnancy and births.”

Ginsburg v. Schlafly

The next decades were a race between two very different women, Ginsburg and Phyllis Schafly from Alton, Il. Ginsburg was taking case after case to the Supreme Court to provide women with equal rights under the Constitution, while Schlafly was convincing state legislators to kill the Equal Rights Amendment for fear of same-sex bathrooms and women in the military. Schlaly said she only needed her husband’s permission to lead her ERA battle.

Both women succeeded.

The ERA still is not part of the Constitution, and Ginsburg won almost complete legal equality by including women as deserving “equal protection.”

In several of Ginsburg’s big cases, her clients were men, not women. Winning equal rights for men transferred equality to women.

Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, grew out of the tragic death of Paula Wiesenberg who died while giving birth to her son, Jason.

On Friday, June 2, 1972 Paul had taught school as usual. On Monday, she was dead. Unexpected labor complications caused her lungs to fill with fluid, which led to cardiac arrest.

Jason was the couple’s first child. Wiesenfeld didn’t even know how to change a diaper.

Because Paula had paid into the Social Security system for seven years, Jason was eligible for $206.90 a month. Wiesenfeld asked if he was eligible.

“You would be if you were a woman,” he was told. It made no difference that Paula had been the family’s primary breadwinner.

Wiesenfeld hired a succession of five housekeepers who didn’t work out. He quit computer programming and opened a bike store so he could spend more time with his son.

When a local newspaper wrote a story about men at home, he wrote a letter to the editor. A professor at nearby Rutgers University saw the letter and put him in touch with the Women’s Rights Project of the ACLU, which was run by Ginsburg. Ginsburg made sure Wiesenfeld sat right behind her at oral argument so the all male justices could see his face and sympathize.

The court ruled unanimously in his favor. “It’s no less important for a child to be cared for by its sole surviving parents when that parent is a male rather than a female,” Justice Brennan wrote for the court. Ginsburg lived to see Jason enter her alma mater, Columbia University law school.

The other victory for women won with a male client was Craig v. Boren, which ended up allowing fraternity men to buy near beer at 18 rather than 21.

Curtis Craig, a fraternity brother at Oklahoma State University, joined the owner of Honk ‘n’ Holler, a local liquor store, to challenge a state statute that permitted the sale of 3-2 beer to women because they were more refined drinkers who could handle their liquor.

Ginsburg called it a “gossamer” case, “a non-weighty interest pressed by thirsty boys.” Ginsburg showed that the state didn’t have evidence that its law had any effect on traffic safety and noted it was based on stereotypes and generalities. She convinced the all-male bench to use a new, tougher test for sex discrimination. The new standard was more demanding than the lowest standard for review the court uses – rational basis – but less demanding than the highest standard – strict scrutiny, used in race cases. The court adopted an in-between standard – intermediate scrutiny. That made it easier to challenge laws that favored one sex.

VMI

The pinnacle of Ginsburg’s legal career was the opinion she wrote as a justice on the Supreme Court throwing out the male-only admission requirement of the Virginia Military Institute, a male bastion.

In an extraordinary public announcement of the decision from the bench, Ginsburg said a state violated equal protection when it “denies to women simply because they are women equal opportunity to aspire, achieve, participate in, and contribute to society based upon what they can do.”

“…reliance on overbroad generalization typically male or typically female tendency estimates about the way most women or most men are will not suffice to deny opportunity to women whose talent and capacity place them outside the average description…state actors may not close entrance gates based on fixed notions concerning the roles and abilities of males and females.”

The Constitution, she said, does not justify “the categorical exclusion of women from an extraordinary educational leadership development opportunity afforded men. …women seeking…a VMI quality education cannot be offered anything less.”

The lone dissenter, Justice Antonin Scalia, issued a characteristically tart dissent calling it “one of the unhappy incidents of the federal system that a self-righteous Supreme Court, acting on its Members’ personal view of what would make a “‘more perfect Union,’…”

What is a woman?

During Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation hearing Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) asked a seemingly simple question – “what a woman is.”

Jackson’s response was by turns puzzled, nervously amused and then lawyerly in saying she couldn’t define the word without knowing the legal context.

The brief confrontation was one of those moments that captures the public imagination because suddenly all of the complexities of the Supreme Court are boiled down to one simple question a kindergartner might answer but a brilliant Harvard Law graduate would not. The exchange quickly became big news on Fox and other right-leaning media sites that used it in an unsuccessful attempt to derail her nomination.

Blackburn quoted a passage from Justice Ginsburg’s opinion in the VMI case: ‘Supposed “inherent differences” are no longer accepted as a ground for race or national origin classifications. Physical differences between men and women, however, are enduring. The two sexes are not fungible.”

Blackburn asked Jackson if she agreed physical differences between men and women are enduring? The senator’s political point was clear, however: Jackson’s inability to define a woman underscores the “dangers of the progressive education that allows children to talk about their sexual identities.”

“Just last week,” Blackburn added, “an entire generation of young girls watched as our taxpayer funded institutions permitted a biological man to compete and beat a biological woman in the NCAA,” a reference to Lia Thomas, a champion transgender swimmer on the University of Pennsylvania’s women’s team.

Critics pointed out that Blackburn has a long record of opposing laws that Ginsburg had supported as a lawyer or upheld as a justice. Blackburn voted against the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act and opposed ratification of the ERA.

Jackson finally found a way not to answer the question. She pointed out that the definition of sex in the law was an issue that is likely to come before the court, so she should not express an opinion.

One interesting footnote is that Justice Neil Gorsuch, one of the most conservative justices on the court, wrote the decision in 2020 holding that the word sex includes sexual orientation and gender-identity.

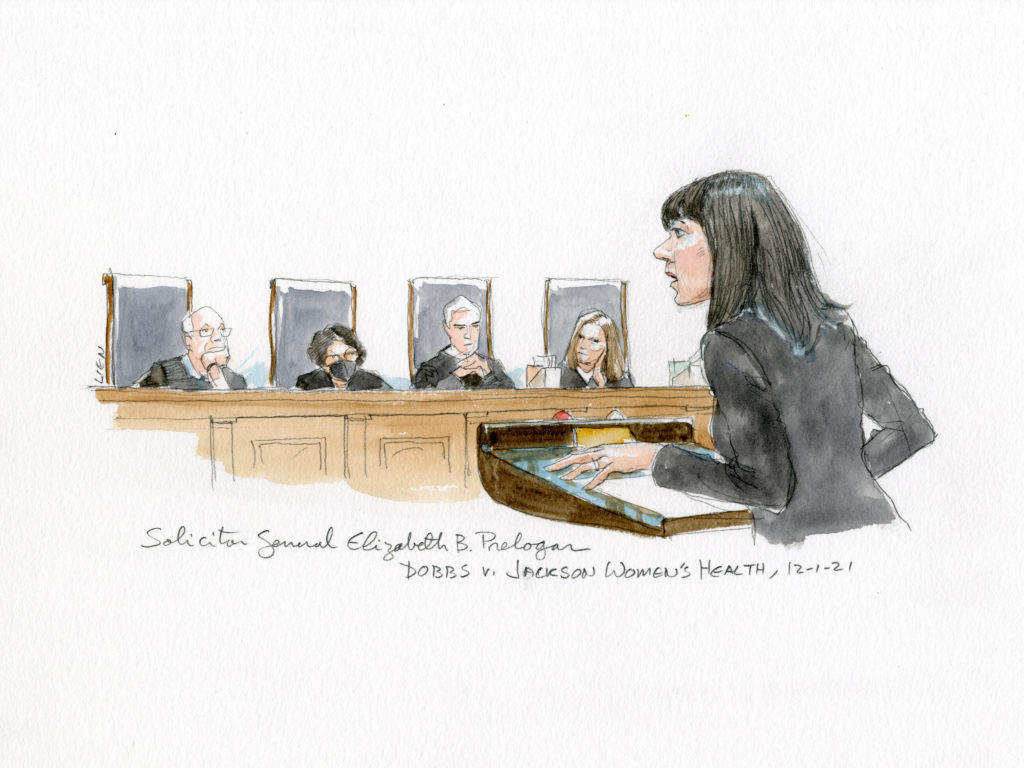

Where were the women in Dobbs

In his majority opinion in Dobbs, Justice Alito quickly dismissed the equality dimension that Planned Parenthood v. Casey added in affirming Roe. That equality dimension was that control of reproduction was necessary for women “to participate equally in the economic life and social life of the nation.”

Alito maintained that “a State’s regulation of abortion is not a sex-based classification,” citing a 1976 decision where women employees were denied health benefits for pregnancy.

Alito added that “this Court is ill-equipped to assess “generalized assertions about the national psyche.’” Casey’s notion of reliance on precedent was not as concrete as reliance interests are when “property and contract rights” are involved,” he said.

Alito also cited a number of equal rights advances for women as making abortion unnecessary for women to have an equal place in society.

He wrote that “‘modern developments’ in society’s attitude toward women make these equality arguments outmoded, arguing that ‘…attitudes about the pregnancy of unmarried women have changed drastically; that federal and state laws ban discrimination on the basis of pregnancy, that leave for pregnancy and childbirth are now guaranteed by law in many cases, that the costs of medical care associated with pregnancy are covered by insurance or government assistance; that States have increasingly adopted safe haven laws, which generally allow women to drop off babies anonymously; and that a woman who puts her new-born up for adoption today has little reason to fear that the baby will not find a suitable home.”

A controversial footnote that Alito added, quotes the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stating that “the domestic supply of infants relinquished at birth or within the first month of life and available to be adopted had become virtually nonexistent.”

Legal commentator Emily Bazelon of The New York Times wrote that Alito’s decision was ignoring the reality of a woman’s life. Quoting from an amicus brief by economists, she wrote: “Pregnant people are still denied accommodations at work, despite a 1978 law that’s supposed to protect them from discrimination. Women still experience an economic ‘motherhood penalty.’ And the financial effects of being denied an abortion…are ‘as large or larger than those of being evicted, losing health insurance, being hospitalized or being exposed to flooding’ resulting from a hurricane.”

Linda Greenhouse, the Times’ long-time Supreme Court reporter, wrote in a companion article that she was shocked that women were almost entirely absent in the Alito opinion. It is “astonishing that in 2022 he would use his power to erase the right to abortion without in any way meaningfully acknowledging the impact both on women and on the constitutional understanding of sex equality as it has evolved in the past half-century.”

Click here to support Gateway Journalism Review with a tax-deductible donation. (GJR was founded as the St. Louis Journalism Review.)

William H. Freivogel is a professor and former director of the School of Journalism at SIUC. He is the publisher of Gateway Journalism Review.