The nation’s fight about the meaning of America’s great promises of freedom and equality played out at St. Louis’ Old Courthouse in 1850 and before huge crowds in the seven Illinois towns during the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858. It took the death of 750,000 men to settle the issue.

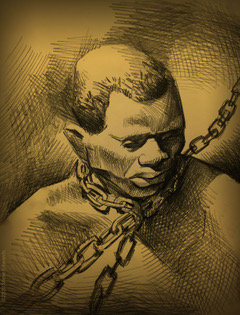

Five paragraphs beyond those stirring words “We the People” is a shock – the three-fifths compromise. Keep reading and you find protection for the slave trade and the fugitive slave provision, although the Framers were careful never to use the word slavery.

When the nation celebrated the 200th anniversary of the Constitution in 1987, Justice Thurgood Marshall, the nation’s first black justice, upset quite a few Americans with a less than enthusiastic appraisal of the Constitution.

He said the Constitution “was defective from the start, requiring several amendments, a civil war and momentous social transformation to attain the system of constitutional government, and its respect for the individual freedoms and human rights we hold as fundamental today.

“No doubt it will be said, when the unpleasant truth of the history of slavery in America is mentioned during this bicentennial year, that the Constitution was a product of its times and embodied a compromise which, under other circumstances, would not have been made. But the effects of the Framers’ compromise have remained for generations. They arose from the contradiction between guaranteeing liberty and justice to all, and denying both to Negroes.”

Marshall was right. Thirteen of the 55 men who wrote the Constitution were slaveholders – including three of the first four presidents, Washington, Jefferson and Madison – and all 55 were white and wealthy. Benjamin Franklin was president of a group called the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. But neither Franklin nor any other delegate called for abolition at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787.

Yet there was pressure mounting for abolition. Thomas Jefferson fell one vote short of getting slavey abolished in the territories. In a compromise, the Congress of the Confederation passed the Northwest Ordinance that same year, 1787, banning slavery north of the Ohio River, including Illinois.

Meanwhile, the framers of the Constitution were struggling with slavery, according to historical accounts including James Madison’s diaries. In June of 1787, the Constitutional Convention came up with the three-fifths compromise stating that representation would be proportioned to the “whole number of white and other free citizens and three-fifths of all other persons except Indians not paying taxes…”

That didn’t mean that slaves were three-fifths of a person. They were property, not persons at all.

The three-fifths referred to the additional political power given white slave owners. White slave owners essentially had their own vote plus three-fifths of the votes of slaves. Jefferson became president in 1800 as a result of the three-fifths compromise. The 15 electoral votes that slaves added to the South provided his margin of victory.

Further on, the Constitution contained more strange wording to express compromises over the slave trade and fugitive slaves. “The Migration or Importation of Such Persons as any of the States now-existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.”

And the fugitive slave provision required that persons who escaped from “service or Labour in One State” must be returned to “the Party whom such Service or Labour may be due.”

Alexander Hamilton wrote that without the slavery compromises “no union could possibly have been formed.”

There was a big argument over slavery at the end of August that summer. Luther Martin of Maryland proposed a tax on the importation of slaves, calling slavery “inconsistent with the principles of the revolution.”

John Rutledge of South Carolina responded, “Religion and humanity had nothing to do with this question. Interest alone is the governing principle of Nations…If the Northern States consult their interest, they will not oppose the increase of slaves which will increase the commodities of which they will become carriers.”

George Mason of Virginia, a tall, white-haired plantation owner and major slave holder, gave the most impassioned and prescient speech about slavery at the Convention. He said slaves “bring the judgment of heaven on a country. As nations cannot be rewarded or punished in the next world, they must be in this. By an inevitable chain of causes and effects, providence punished national sins by national calamities.”

The national calamity lay seven decades ahead and it ran through Missouri and Illinois.

The Missouri Compromise – ‘Like a fire bell in the night’

Two hundred years ago, while many of the Founders still were alive, Missouri came to the forefront of the slavery fight. It has been inextricably entwined in the nation’s struggle over race ever since.

Jefferson, as president, had persuaded Congress to abolish the slave trade at the earliest possible time,1808. But the slavery issue heated up again with the Missouri crisis of 1819. Northerners were alarmed that Mississippi and Alabama had recently been admitted as slave states. Now Missouri, which was north of the Mason-Dixon line, wanted admission as a slave state too.

Rep. James Tallmadge Jr. of New York passed a House amendment to the Missouri bill that prohibited the “further introduction of slavery” and freed slaves at age 25. Tallmadge had made a name for himself opposing Illinois’ black codes denying free blacks the rights of citizenship. But the Senate refused to go along with Tallmadge’s amendment.

Missourians were mad at Tallmadge. Southern planters had brought 10,000 slaves to Missouri, many in Little Dixie in Southeast Missouri where they worked on cotton and others in the western part of the state raising hemp.

Every Missouri newspaper opposed the Tallmadge amendment. Thomas Hart Benton’s St. Louis Enquirer editorialized: “Suppose the worst came to the worst and Congress actually passed the law to suit the views of the New England politicians, would Missouri submit to it? No! Never!”

Under the Missouri Compromise of 1820, drafted by Sen. Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois, himself a slaveholder, Missouri was admitted as a slave state and Maine as a free state. That retained the numerical balance of slave and free states. Congress banned slavery in the portion of the Louisiana Purchase above the southern border of Missouri. The compromise passed 90-87.

Jefferson opposed the compromise and expressed forboding that it spelled dissolution of the Union. He wrote a friend, it was “like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. it is hushed indeed for the moment. but this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.”

St. Louis greeted passage, wrote historian Glover Moore, “with the ringing of bells, firing of cannon” and a transparency showing “a Negro in high spirits, rejoicing that Congress had permitted slaves to be brought to so fine a land as Missouri.”

Pro-slavery politicans overwhelmed opponents and controlled the state constitutional convention in St. Louis in the summer of 1820. One provision of that state constitution guaranteed the perpetuity of slavery, and another barred free blacks and mulattoes from entering the state.

Those provisions threw Congress back into a crisis. It passed a second Missouri Compromise authorizing the president to admit Missouri only after the Legislature promised not to discriminate against citizens of other states.

Missourians again were furious. At an 1821 meeting in St. Charles, the Legislature adopted the resolution demanded by Congress, while at the same time declaring the resolution meant nothing. The state constitution would “remain in all respects as if the said resolution had never passed.” Later, in 1847, the Legislature passed a law declaring “no free negro, or mulatto shall, under any pretext, emigrate to this State from any other State.” In other words blacks could be brought as slaves but not come as free persons.

That same year Missouri passed a law making it illegal to teach blacks. “No persons shall keep or teach any school for the instruction of mulattos in reading or writing,” it read. A few brave teachers took skiffs into the Mississippi River to evade the law.

Lovejoy to Dred Scott

St. Louis had both pro- and anti-slavery elements. Elijah P. Lovejoy, editor of the St. Louis Observer, a Presbyterian weekly, angered pro-slavery forces with his abolitionist editorials.

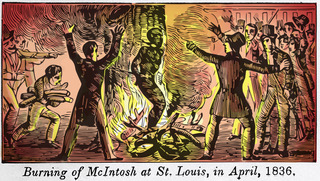

On April 28, 1836, the mulatto cook on the steamboat Flora, Francis McIntosh, was arrested by police in St. Louis for disturbing the peace. When a policeman told him he would spend five years in jail, he stabbed one officer to death and seriously injured another officer. He escaped but a mob found him hiding in an outhouse. The mob, which grew to several hundred, chained him to a tree near 7th and Chestnut, piled wood up to his knees and burned him to death while he pleaded for them to shoot him. (The murder was one block from where the bucolic Citygarden Sculpture Park now stands, an urban oasis for St. Louis families and visitors.)

The aptly named presiding judge over the grand jury, Luke Lawless, decided McIntosh’s death was the result of a mass phenomenon and that no individuals should be prosecuted. Judge Lawless said McIntosh was an example of the “atrocities committed in this and other states by individuals of negro blood against their white brethren,” adding that because of abolitionist agitators “the free negro has been converted into a deadly enemy.” Lawless also misinformed the jury that McIntosh was a pawn of Lovejoy’s.

A week later, Lovejoy editorialized that the lynching meant the end of the rule of law and the Constitution in St. Louis. Only one lawmaker in Missouri and Illinois condemned the lynching. His name – Abraham Lincoln.

After Lovejoy’s May editorial, a mob of toughs from downtown taverns destroyed Lovejoy’s press and threw parts into the Mississippi.

Lovejoy moved across the river to Alton, which was officially a free state, although it was also home to slave catchers looking to capture slaves who escaped from Missouri.

In November, 1937, a few weeks after Lovejoy held the Illinois Anti-Slavery conference at his church, a mob burned his warehouse and murdered Lovejoy as he tried to push down a ladder used by the arsonists. His press was thrown out of the warehouse and onto the river bank where it was broken into parts and thrown in the river.

HUNDREDS OF FREEDOM SUITS

Today we hear about only Dred and Harriet Scotts’ suit for freedom. But about 300 slaves filed freedom suits in St. Louis during the years from 1805 until the Dred Scott decision. Some won.

Marguerite Scypion brought one of the first “freedom suits” in 1805. She was a daughter of a black slave and a Native American mother of Natchez descent. She and her sisters argued that they were free because Spain had abolished Indian slavery when it controlled St. Louis in the late 18th Century.

Scypion initially won, but appeals courts overturned the decision and she and her family remained slaves, at one point owned by Jean Pierre Chouteau, a prominent merchant and fur trader.

Scypion renewed her family’s suit after the Missouri Legislature passed a law in 1824 opening the way for slaves to sue for freedom. She claimed Chouteau had assaulted her and falsely imprisoned her. The case was transferred to Jefferson County because of the Chouteaus’ influence in St. Louis. In 1836 she and her family won their freedom and two years later the appeals courts agreed, ending Indian slavery.

‘No rights which the white man would be bound to respect.’

In 1846 Dred and Harriet Scott filed for their freedom arguing they had become free when a former owner took them to free soil in Illinois and Minnesota.

To say the soil was free across the Mississippi wasn’t really true. In 1763 there were 600 slaves in Illinois. The Northwest Ordinance had banned slavery north of the Ohio River, but many Illinois residents, such as Arthur St. Clair, namesake of St. Clair County, had slaves illegally. One way to get around the Northwest Ordinance was to force a slave to put an X on an agreement to become an indentured servant. In essence, Illinois operated as a slave state.

Illinois passed a draconian Fugitive Slave law in 1819 that empowered whites to stop blacks and challenge their freedom. Slaves were bought and sold in the state until 1845 and involuntary servitude did not end until 1848.

The Scotts’ case was tried in the Old Courthouse in St. Louis in a courtroom on the opposite side of the courthouse from the steps facing the Mississippi River where slaves were bought and sold.

The Scotts actually won their case in St. Louis in 1850. But the Missouri Supreme Court ignored its precedents and kept the Scotts in slavery. The judges worried about the growing power of abolitionists, remarking on the nation’s “dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery” and adding, “….Under the circumstances it does not behoove the State of Missouri to show the least countenance to any measure which might gratify this spirit.”

The opinion said slaves were far better off than the “miserable” African. “We are almost persuaded that the introduction of slavery among us was, in the providence of God….a means of placing that unhappy race within the pale of civilized nations.”

In the most infamous decision in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court, Chief Justice Roger Taney concluded on March 6, 1857 that blacks “are not included and were not intended to be included, under the word citizens in the Constitution.”

“We the people” did not include blacks. “They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order,” wrote Taney, “…and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit…..”

Taney said the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional because Congress had no power to ban slavery in the territories.

Slaves were property protected like any other property by the Fifth Amendment of the Bill of Rights, the court said. So, when the Fifth Amendment said “no person” shall be “deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” it protected property rights of white people to take away the liberty rights of black people who weren’t people under the Constitution.

A year later, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas drew throngs throughout Illinois as they debated the Dred Scott decision and how blacks fit into the vision of freedom and equality created by the then dead Framers.

Lincoln said the Declaration of Independence’s “All men…” had included blacks. Lincoln said the Constitution used “covert” words to refer to slavery because the Framers thought slavery would die. But Douglas said they expected the Constitution to endure “forever” with the country half slave and half free. His idea of “popular sovereignty” would give each new state the opportunity to choose slavery or freedom.

It took the deaths of 750,000 Americans to settle the issue. Settle the issue of slavery that is. Equality is taking a lot longer.

Reading equality out of the Constitution

After the Civil War, the 13th Amendment banned slavery, the 14th barred states from denying people liberty and equality and the 15th protected voting rights.

But as with the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, the broad promises of liberty, equality and suffrage didn’t mean what they said. Rep. James F. Wilson of Iowa, an author of the 14th Amendment said “equal protection” did not mean “that in all things, civil, social, political, all citizens without distinction of race or color, shall be equal….Nor do they mean that all citizens shall sit on juries or that their children shall attend the same schools.” At the same time Congress approved the 14th Amendment’s equal protection guarantee, it segregated D.C. public schools.

Over the next 40 years the Supreme Court gutted and perverted the post-Civil War amendments. The court said the 14th and 15th Amendments did not give blacks the right to vote or live in an integrated society.

Of course women, black or white, weren’t “persons” protected by the 14th Amendment. The court said in a case from Missouri that St. Louisan Virginia Minor couldn’t vote because the “persons” whose equality was protected by the 14th amendment didn’t include women. Nor could Myra Bradwell be admitted to the Illinois bar because she had no right to take legal actions without her husband’s approval. The U.S. Supreme Court said the 14th amendment didn’t make any difference.

Minor and Bradwell were white, but the Supreme Court read blacks out of the equality guarantee as well.

In the 1873 Slaughterhouse Cases the court said the 14th Amendment gave freedmen the rights of national citizenship, but not the rights of state citizenship.

Three years later the court said the 15th Amendment “does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone” even though the amendment states explicitly: “The rights of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The Civil Rights Cases of 1883 grew out of the refusal of inns in Jefferson City, Mo. and Kansas to provide lodging for blacks, a Tennessee train conductor’s refusal to admit a black woman to the ladies car of a train and theatre owners in New York and San Francisco refusing to sell seats to blacks. The court concluded the 14th Amendment’s equality guarantee did not permit Congress to reach this “private” discrimination. That would be “invasion of individual rights.”

Finally, Plessy v. Ferguson – upholding Louisiana’s denial of a seat on the white railroad car to Homer Plessy because he was one-eighth black – enshrined “separate but equal” as the meaning of “equal protection” for the next 58 years until Brown v. Board tossed it in the dustbin of the court’s ignominious decisions, along with Dred Scott.

The court said in Plessy the 14th Amendment “could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either….If one race be inferior to the other socially, the (Constitution) cannot put them on the same plane,” wrote Justice Henry Billings Brown.

St. Louis’ schools were segregated until Brown and after. Before Brown, black students in St. Louis suburbs were denied admission to their local high school and sent to black St. Louis high schools instead. Members of the African American Carter family of Breckenridge Hills told me 50 years ago of the humiliation of having to pay for their own bus fare to Sumner and then to have to lie about their address to be admitted. Kirkwood students also were bussed to Sumner. https://www.newspapers.com/image/140669869/

At the same time that the Supreme Court was reading blacks and women out of the post-Civil War amendments they were finding plenty of room to protect predatory business practices. The 14th amendment protected the right of contract, the court decided, making minimum wage, maximum hours and child labor laws unconstitutional. In the 1905 Lochner decision it threw out New York’s Bakeshop law limiting bakers’ hours to 10 a day and 60 a week. The court held that the law interfered with the worker’s liberty to decide how many hours are “appropriate or necessary for support of himself and his family.”

The 20th Century – ‘SAVE YOUR HOME! VOTE FOR SEGREGATION’

In 1916 — just before the deadly East St. Louis race riots — St. Louisans voted by a 3-to-1 margin to pass a segregation ordinance prohibiting anyone from moving into a block where more than three-fourths of the residents were of another race.

A leaflet with a photo of run-down homes said: “Look at These Homes Now. An entire block ruined by the Negro invasion….SAVE YOUR HOME! VOTE FOR SEGREGATION.”

As so often was the case, supporters of the discriminatory legislation couched it in paternalistic terms of what was good for black people.

The St. Louis supporters said it was needed “for preserving peace, preventing conflict and ill feeling between the white and colored races in the city of St. Louis, and promoting the general welfare of the city by providing….for the use of separate blocks by white and colored people for residence, churches and schools.”

The St. Louis ordinance – replicated in a dozen cities from Baltimore to Oklahoma City – fell by the wayside when the Supreme Court struck down a similar law in Louisville in the 1917 Buchanan v. Warley decision.

But the court helpfully suggested in another case that real estate covenants, barring sales of houses to blacks, would be a legal way to segregate housing because they didn’t involve state discrimination. St. Louis took up the suggestion, widely using restrictive covenants on home deeds, preventing sale to blacks. Many trust indentures excluded “Malays” — along with blacks and Jews — because Malays were displayed in the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis.

By the end of World War II, blacks in St. Louis were mostly segregated within a 417-block area near Fairground Park, partly because of these restrictive covenants. About 117,000 people lived in an area where 43,000 had lived three decades earlier.

Biggest race riot of its time

During the great migration of blacks from South to the North, thousands of blacks arrived at the meatpacking town of East St. Louis, just across from America’s fourth largest city. Many blacks couldn’t get jobs and ended up in shanties in the river bottoms.

Sensationalist newspaper stories led many whites to believe blacks were on a crime spree. But crime and a Wild West atmosphere had long prevailed in East St. Louis. There is little evidence of the “reign of crime” by blacks.

But blacks were competing with whites for jobs. Non-union strikebreakers, some of them black, forced white unions into collapse.

White mobs began to attack blacks through the spring and summer of 1917 before a wholesale race riot exploded on July 2, 1917. By the end of the long, hot day hundreds of blacks had been brutally attacked, thousands fled the city and more than 300 homes and places of business had been destroyed by fire. White rioters threw many blacks from bridges into the Mississippi.

The dozens, maybe hundreds of blacks murdered were the biggest racial bloodbath until the Los Angeles riots after the acquittal of police officers in the Rodney King beating 75 years later.

The East St. Louis riot was followed by a violent riot in Houston later in the summer and by the Red Summer of 1919, when two dozen cities and towns experienced deadly riots. And then came Tulsa two years later with an official death toll of 36 people, two-thirds black.

More than 200 African Americans were lynched in Missouri and Illinois in the century from the 1840s to 1940s, often in a carnival-like atmosphere with families watching. The Ku Klux Klan was at a high point of power in the years right after World War I. Klan members in Indiana included the governor, more than half the legislature and 250,000 white men.

House on Labadie

J.D. Shelley came to St. Louis before World War II and had a job in the small arms factory on Goodfellow during the war. He recalled later, “When I came to St. Louis, they had places like the Fox Theater, no colored could go there; and the baseball diamond up on Sportsman’s Park, they didn’t allow no colored in there at one time. When they did open up Sportsman’s Park for colored, onliest place they could sit was in the bleachers. That changed after the war…”

In 1945 Shelley wanted to buy a house at 4600 Labadie for his wife and six children who joined him from Mississippi. But a restrictive real estate covenant barred sale to “persons not of Caucasian race.”

Neighbors down the street at 4532 Labadie, Louis and Ethel Kraemer, sought to enforce the covenant. James T. Bush Sr., the black real estate agent who had sold the property to the Shelleys, formed an association to pay for the Shelley’s court costs. The lawyer for the association was Bush’s promising daughter, Margaret Bush Wilson, who went on to have a storied civil rights career.

George L. Vaughn, a noted African American lawyer, argued Shelley’s case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Vaughn said he wasn’t seeking integration. “Negroes have no desire to live among the white people,” he said. “But we were a people forced into a ghetto with a resultant artificial scarcity in housing.”

In the 1948 decision, Shelley v. Kraemer, the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed judicial enforcement of racial covenants. The involvement of the state courts in enforcing the covenants made this a state action, not just private discrimination, the court said.

About the same time, the city tried to integrate nearby Fairground swimming pool, a huge pool just north of Sportsmen’s Park where the Cardinals were winning three World Series in the 1940s. It could accommodate 10,000 swimmers. Forty black children needed a police escort to leave the pool in what Life magazine called a “race riot” on the first day of summer 1949. White youths wielded baseball bats and chased black youths through the streets. The Star-Times quoted a middle age white man shouting “Kill a n—-r and make a name for yourself.”

The Life story read, “In St. Louis, where the Dred Scott case was tried, the cause of racial tolerance seemed to be looking up last week. A negro police judge took office for the first time, and the Post-Dispatch hired its first Negro reporter. But when the city opened all of its swimming pools to Negroes on June 21…progress stopped….police had to escort 40 Negro swimmers through a wall of 200 sullen whites.”

The mayor immediately reimposed segregation at the pool. The city’s official report said it had been unfair to call the disruption a riot. (I never asked my dad about the riot, which occurred a month before I was born. My dad had been a lifeguard at the pool for many years before the riot and lived with his parents in the janitor’s quarters of the Christian Science church across the street.)

FHA meant blacks need not apply

Federal housing policies after World War II discriminated against blacks by subsidizing rapid expansion of all-white suburbs while building largely segregated public housing projects.

Carr Square was built for blacks and Clinton Peabody for whites.

Pruitt-Igoe, built in 1955-6 was Pruitt for blacks and Igoe for whites. Architecture Review praised it as “vertical neighborhoods for poor people.” The project quickly became all black and symbolized the failure of public housing when it was blown up in 1972.

In a crusade to clean up the slums, St. Louis displaced thousands of people who lived in the Mill Creek Valley “slum” just west of downtown, near the railroad tracks. But people didn’t pay attention to those displaced. By the 1970s and 80s the city began tearing down the bleak, dilapidated public housing towers. Pruitt-Igoe was dynamited in 1972. (I remember as a privileged boy from Kirkwood driving through Mill Creek and throwing a bag of my old clothes out the window. I wanted to help the children, but we were afraid to actually talk to them.)

The words – “FHA financed” – in housing ads were code for blacks need not apply, writes Richard Rothstein in an Economic Policy Institute report on the root causes of the Ferguson protests. An FHA underwriting manual called for “protection against some adverse influences” adding “the more important among the adverse influential factors are the ingress of undesirable racial or nationality groups.”

The U.S. Civil Rights Commission, which came to St. Louis in 1970, concluded: “Federal programs of housing and urban development not only have failed to eliminate the dual housing market, but have had the effect of perpetuating and promoting it.”

Through the last part of the 20th century black enclaves in suburban St. Louis were wiped out or carved up by redevelopment in St. Louis County from Clayton to Brentwood to Kirkwood. Praised as urban renewal, they were often actually “Negro removal.”

A black Clayton neighborhood once prospered where the Ritz-Carlton stands. A black neighborhood in Brentwood gave way to the upscale Galleria. Part of Kirkwood’s Meacham Park was gobbled up for a Target and many residents had to move out to north county.

Need for a playground

Suburban communities used exclusionary zoning to keep out black families. Howard Phillip Venable, a noted African-American eye doctor, and his wife Katie were building a house in Spoede Meadows in Creve Coeur in 1956. Dr. Venable was chair of Ophthalmology at Homer G. Phillips Hospital and St. Mary’s Infirmary and joined the Washington University Medical School faculty.

Spoede Meadows was an idyllic spot. Other African Americans wanted to buy lots nearby but were dissuaded by a local “white citizens committee.”

Venable’s application for a plumbing license was denied. Suddenly, the city discovered a need for a new park, right on Venable’s property and used eminent domain to take his land. U.S. District Judge Roy Harper, notoriously opposed to civil rights, tossed out Venable’s suit. The park stands today where the late doctor wanted to live. Creve Coeur last year recognized the bigotry and renamed the park for the late doctor.

In 1964, Joseph Lee Jones, a bail bondsman and his wife, Barbara, applied for a “Hyde-Park style” house in the Paddock Woods subdivision, five miles due north of the current Canfield Green apartments in Ferguson where Michael Brown died. Alfred H. Mayer Co. refused to sell the home.

Lawyer Sam Liberman took Jones’ case to the U.S. Supreme Court, even though the liberal American Civil Liberties Union refused to back the suit because it interfered with private property purchases. Liberman won. The court ruled the Constitution protects “the freedom to buy whatever a white man can buy, the right to live wherever a white man can live….when racial discrimination herds men into ghettos and makes their ability to buy property turn on the color of their skin, then it … is a relic of slavery.”

Shortly after Jones v. Mayer, the Inter Religious Center for Urban Affairs planned to build Park View Heights, integrated, subsidized townhouses in an unincorporated area of north St. Louis County, not far from the Jones’ house in Paddock Woods. Local opposition developed in the area that was 99 percent white and residents incorporated as the city of Black Jack. The new town promptly passed a zoning ordinance that barred construction.

Judge Harper threw out the challenge to this discriminatory zoning. A federal appeals court overturned the decision.

Appeals judge Gerald Heaney, who was as famous for his pro-civil rights decisions as Harper was notorious for opposing civil rights, wrote that when a law had a discriminatory effect, the burden is on the city to show it has a strong, non-discriminatory purpose. Black Jack didn’t have such a purpose.

Although residential racial segregation has declined in St. Louis and most other cities, St. Louis was the seventh most racially segregated metropolitan area based on the 2010 census, ranking after other rust belt cities such as Milwaukee, New York/New Jersey, Chicago, Cleveland and Buffalo.

Leland Ware, a former St. Louisan and professor at the University of Delaware, says the 1968 Fair Housing law was largely a “toothless tiger” with weak enforcement. “Lingering vestiges of segregation remain in the nation’s housing markets that “perpetuate segregated neighborhoods.” Hear Richard Baron tell about the St. Louis rent strike and Black Jack.

St. Louis’ Selma – ‘Anatomy of an Economic Murder’

There never was a civil rights riot in St. Louis in the 20th century, a fact often cited as a reason St. Louis never seriously grappled with race.

One reason there was no riot was the Jefferson Bank protests of 1963, the birthplace of that generation’s black leaders. William L. Clay, who went on to Congress, led the sit-in blocking the bank’s doors.

CORE, the Congress on Racial Equality, sparked the demonstrations at Jefferson Bank, which started two days after 250,000 people joined the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington, demanding passage of the Civil Rights Act. Other civil rights groups, such as the local NAACP and Urban League, shunned CORE’s tactics.

Clay was a young black alderman at the time. He received the longest of the jail sentences: 270 days in jail and a $1,000 fine. He often was criticized in the news media for breaking the law, and opponents tried unsuccessfully to oust him as alderman.

Clay recalled in an interview with former reporter Robert Joiner that he never thought of giving up. “I was surrounded by other people with the same kind of commitment. Ivory Perry, Percy Green, Marian Oldham and Bob Curtis — these were people who weren’t going to give up, and I certainly wasn’t going to give up. We’d been challenging the system for 10 years before Jefferson Bank through demonstrations at other sites in St. Louis, so we had never felt like giving up.”

Clay published a 27-page survey called “Anatomy of an Economic Murder.” It contained data from major businesses in St. Louis on how many employees they had, and how many were blacks.

The survey showed 37 blacks out of 7,325 workers at breweries; 69 blacks out of 3,107 sales and office jobs at five department stores; 51 blacks among 1,505 at nine dairies; 279 blacks (most in menial jobs) among 1,303 soft-drink workers; 277 blacks (99 percent in minimum-wage jobs) of 5,133 at 16 banks; 22 blacks out of 2,141 at seven insurance companies; and 42 blacks out of 2,550 employees at the two major newspapers.

None of the five inner-city car dealers had a black salesman or mechanic. Neither of two industrial firms (each with 900 employees) had a single black on the payroll. No blacks worked as salespersons in downtown department stores, and no black drivers for beer, dairy and soft-drink companies. The electric, gas and telephone companies, employing thousands, did not hire black linemen, telephone operators, meter readers, stenographers or clerks.

Clay was criticized for embarrassing the firms and hurting the image St. Louis had cultivated as a progressive city in race relations.

While Jefferson Bank, which received city revenues, refused to change its hiring policy, other employers did out of fear CORE would target them. Blacks gained about 1,300 jobs as a direct result of the demonstrations.

Police infiltrated spies into CORE to gather intelligence on the group’s plans and the bar tried to disbar lawyers involved.

Clay published a book in 2008 called “The Jefferson Bank Confrontation, The Struggle for Civil Rights in St. Louis.” The front of the book shows Clay’s daughter Michelle picketing with a sign reading, “Give My Mom a Job.” Twenty years later, as a candidate for the Missouri Bar, she was interrogated about her role at the bank. She had been 5 years old at the time she carried the sign.

Jefferson Bank Executive Vice President Joseph H. McConnell said at the time of the protests, “When aldermen and ministers and physicians picket your bank and block police vehicles, we wonder what our society is coming to.”

Climbing the Arch for jobs

CORE’s tactics were too militant for St. Louis’s businesses, newspapers and even its chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, which was upset the demonstrators were breaking the law by blocking entrance to private businesses.

But CORE’s tactics weren’t muscular enough for Percy Green, who started ACTION in 1964, calling for “direct action” to gain civil rights. He didn’t think the Jefferson Bank protesters had asked for enough jobs and he wanted to show that civil rights protesters would not be frightened off by the harsh court penalties on Jefferson Bank protesters.

Green attracted attention by climbing the partially built Gateway Arch, unmasking of the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan and filing a historic job discrimination case again McDonnell Douglas.

Green and a white friend climbed one leg of the Arch on July 14, 1964 to demand that 1,000 black workers be hired for the $1 million construction project. There were no black workers on the Arch construction project. He followed up demanding 10 percent of the jobs at utility companies — Southwestern Bell, Union Electric and Laclede Gas.

“Southwestern Bell had no telephone installers at the time,” he recalled in an interview. “Laclede Gas had no meter readers…..We managed to expose them to the extent that they had to start hiring blacks in those areas. I think the first black…telephone installer eventually retired as a top-notch official. At the time the excuse they gave for blacks not being telephone installers….was they felt that these black men would create problems by going into white homes. That’s what the president of the company said and a similar excuse was given me by the president of Laclede Gas.”

A month after Green’s protest at the Arch, McDonnell Douglas laid him off saying it was part of a workforce reduction. Green thought the company was punishing him for climbing the Arch. ACTION held a stall-in near McDonnell Douglas to protest. Later, Green sued McDonnell. He lost, but the test laid out a national precedent making it easier for people to prove job discrimination.

In 1972, Green organized the unmasking of the Veiled Prophet. The Veiled Prophet ball was a relic of the Old South, with St. Louis’ richest leaders in business dressing up in robes that some people thought looked like Ku Klux Klan outfits. Meanwhile, their debutante daughters paraded in evening gowns. (I remember carriages took the debutantes in their gowns around the city streets in horse-drawn carriages waving like royalty to ordinary families gathered in crowds along Grand Blvd.)

“We realized,” Green recalled, “that the chief executive officers who we had met with about these jobs also was a member of this organization and we put two and two together. No wonder these people don’t hire blacks because they are socially involved in these all-white organizations…. (And) they auctioned off their daughters…. The fact that I used that language was very disturbing to these people. Here these same chief executive officers, racist in terms of their employment, they also were sexist in not allowing their females to live their lives.”

In the late 60s, ACTION had its own black VP ball and the black VP and black queen would try to attend the ball. They would always be denied admission and arrested.

Then in 1972, a woman from ACTION, the late Gena Scott, lowered herself to the stage along a cable and unmasked Monsanto’s executive vice president Thomas K. Smith. The city’s newspapers did not print Smith’s name. Only the St. Louis Journalism Review published the name. After that, the Veiled Prophet took steps to desegregate, but Green makes it clear that his group wasn’t seeking entry, but rather was trying to pressure top business leaders to provide more jobs for blacks.

When Green heard about the death of Michael Brown, “deep down I felt this was another outright murder and is no different from what happened before. ….They (police) say they fear for their life, but at no time does a person fear for their life that they show any indication of taking cover….They say they fear for my life, boom, boom, boom.

“None of this is new,” says Green. Law enforcement demonizing black men goes back to slavery, he said. The only way for law enforcement to gain the confidence of people“is for the Establishment to charge, convict and put in jail for long periods of time policemen who murder black folk, black males….Prosecuting attorneys should also be jailed for abuse of their authority (for) their conduct to allow for these policemen to get away with murder and then these judges who use their benches to justify policemen executing black males.”

Listen to him recount his years as a civil rights leader.

‘No stone unturned’ to preserve segregation at Mizzou

Missouri segregated its schools longer than most southern states. It wasn’t until 1976 – 22 years after Brown v. Board ruled segregation unconstitutional – that Missouri repealed its requirement of separate schools for “white and colored children.”

Segregation applied to the University of Missouri as well.

In 1938 the U.S. Supreme Court ordered Mizzou to admit Lloyd L. Gaines to its law school or to create a separate one of equal quality. The state took the latter option, turning a cosmetology school in St. Louis into the Lincoln University School of law.

University of Missouri President Frederick Middlebush promised to leave “no stone unturned” to block admission of blacks to professional schools.

NAACP lawyers planned to challenge the separate law school Missouri set up, but Gaines vanished without a trace on a visit to Chicago. It never was determined if he had been attacked or wanted to escape the spotlight. It was an era when Missouri had the trappings of Southern society. Schools, housing and education were segregated by law. White mobs lynched blacks at Columbia in 1923, Maryville in 1931 and Sikeston in 1942.

Almost 80 years later, when black students blocked former Mizzou President Tim Wolfe during a homecoming parade – he refused to talk to them about the school’s history of segregation. He was forced to resign.

Minnie Liddell’s mission

Even though Brown v. Board was handed down by the Supreme Court in 1954, it wasn’t until the 1980s that the St. Louis area schools began to desegregate in earnest. One reason is that the legal effort to desegregate ran into not only the South’s Massive Resistance but also the same hostile federal judiciary in St. Louis that had rejected Dr. Venable and the Black Jack suits. U.S. District Judge James C. Meredith ruled there was no legally imposed segregation. But the federal appeals court in St. Louis found the state of Missouri the “primary constitutional wrongdoer.”

Two of Missouri’s most prominent politicians over the past 30 years – John Ashcroft and Jay Nixon – crusaded as attorneys general against the big, ambitious school desegregation plans in St. Louis and Kansas City, each seeking political advantage by attracting opponents of desegregation.

Minnie Liddell wanted her son Craton to attend the nice neighborhood school instead of being bused to a bad neighborhood. Ironically Liddell’s lawsuit led to the nation’s biggest inter-district voluntary busing program in the nation sending about 14,000 black city students to mostly white suburban schools with several thousand suburban children attending magnets in the city.

NAACP lawyer William L. Taylor had pulled together evidence of the complicity of suburban school districts in segregation. Many suburban districts had bussed their students to all-black St. Louis high schools. Kirkwood, for example, bussed its black students to Sumner.

In 1981, a canny judge and former congressman, William Hungate, put a gun to the head of the suburban districts. Either they would “voluntarily” agree to the inter-district transfer program or he would hear all of the evidence of inter-district discrimination and then probably order a single metropolitan school district. He threw in a carrot to go along with this stick. The state, as the primary constitutional wrongdoer would foot the bill.

The idea of a single metropolitan school district frightened suburban school districts and helped special master D. Bruce La Pierre, a Washington University law professor, persuade them to join the voluntary transfer program.

Ashcroft went to the Supreme Court trying to stop the plan, saying there was nothing voluntary about the court’s requirement that the state pick up the tab – which came to $1.7 billion over the next two decades.

His opposition to school desegregation helped propel him to the governor’s mansion after a primary in 1984 in which desegregation was the leading campaign issue. Ashcroft out demagogued former County Executive Gene McNary in a political ad calling McNary “McFlip-Flop” for supposedly being willing to support the desegregation plan.

Ashcroft called the desegregation plan illegal and immoral and paid for a plane to fly leading anti-busing leaders around the state to attest to his anti-busing bonafides. It was his silver bullet.

Nixon on schoolhouse steps

In the fall of 1997, Attorney General Nixon tried to duplicate Ashcroft’s political magic. He appeared on the steps of Vashon High School, a crumbling symbol of black pride in St. Louis. He announced he would press to end the transfer program and spend $100 million building new black schools in the city. Some black leaders, such as Mayor Freeman Bosley, complained that the transfer program hollowed out city neighborhoods and skimmed off the cream of the students.

Opposition to desegregation did not turn out to be the silver bullet that it had been for Ashcroft. Rep. Bill Clay, the one-time Jefferson Bank protester, convinced President Bill Clinton to pull out of a fundraiser for Nixon. Republican Sen. Christopher S. Bond won a record number of votes in the African American community to defeat Nixon for the Senate

But, in Kansas City, Nixon did win a big court battle against that city’s expansive desegregation plan. This wasn’t the Supreme Court of Brown v. Board. Gone was Justice Thurgood Marshall, who had won Brown as a lawyer. In Marshall’s seat on the court was Clarence Thomas, a former Monsanto lawyer who had received his legal training in Missouri Attorney General John Danforth’s office alongside Ashcroft.

Justice Marshall had thought segregated classrooms harmed black children by stigmatizing them as inferior. Thomas had a different idea of stigma. “It never ceases to amaze me that the courts are so willing to assume that anything that is predominantly black must be inferior,” he wrote.

Thomas was the deciding vote in the 1995 decision effectively bringing an end to school desegregation in Kansas City and to court-ordered desegregation nationwide – but not in St. Louis.

Even though Ashcroft and Thomas both were mentored by Sen. Danforth, the Missouri senator was at the same time a strong proponent of civil rights, as the key Republican author of the Civil Rights Act of 1991, along with Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, D-Mass. That law reversed a series of Supreme Court decisions limiting the reach of job discrimination laws.

A political miracle

In 1998 Attorney General Nixon went to court trying to end the St. Louis program, but U.S. District Judge George Gunn Jr. wouldn’t go along. Instead, he appointed William Danforth, former chancellor of Washington University and Sen. Danforth’s brother, to find a solution. The result was a settlement, approved by the Missouri Legislature, to continue the transfer program indefinitely. This settlement was built on three extraordinary accomplishments.

First, a coalition of rural and urban legislators in the state legislature combined to pass a law approving the continuation of the cross-district transfer program, even though the program had been politically unpopular in parts of the state.

Second, Chancellor Danforth brought along the St. Louis business community, obtaining the support of Civic Progress, St. Louis’ most powerful business leaders. People remember Danforth, a man of few words, getting up at the Civic Progress meeting and telling the captains of business, “We just have to do this.” He pointed to higher graduation rates and college-attendance rates for transferring black students.

Third, taxophobic citizens of St. Louis voted to levy a two-thirds of a cent tax on themselves.

In announcing the settlement of the case, Danforth called it “a historic day” for St. Louis.

Minnie Liddell, the heroic mother whose suit had led to the desegregation plan said, “All I can say is, `Yay, St. Louis.’ This has been a long time coming, yet we have just begun. I’m glad I lived to see a settlement in the case.”

Liddell’s lawyer, Taylor, wrote that St. Louis’ settlement was the best in the nation.

“In many communities around the nation, courts are declaring an end to judicially supervised school desegregation…. But in St. Louis, the state Legislature has offered a financial package that will enable educational opportunity programs to continue for 10 years or more,” he said.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch editorial (which I wrote) was headlined “Voting for a Miracle.”

“This feat makes us the first place in the nation where the democratic institutions of government found a way to preserve the gains of the era of desegregation while making it possible to improve the education of all children. Imagine. This happened in Missouri.”

Today, two decades later, Minnie Liddell, her son Craton and attorney Taylor are dead. The transfer program continues to exist, although it is winding down and schools are resegregating.

Kirkwood’s journey

As a young civic leader, Charles Lee “Cookie” Thornton seemed an unlikely antagonist in a racial drama. Thornton’s mother called him “Cookie” because he was so sweet. Kirkwood residents, white and black, remember his broad smile, his embrace and his greeting: “Praise the Lord.” Even a few weeks before the City Hall murders, Thornton would greet friends with his happy-go-lucky attitude and say everything was “FAN-tastic.”

Few African Americans in Kirkwood had so many white friends. He had been a popular track star at Kirkwood High School. In the 1990s, he served on half a dozen civic boards and tutored third and fourth graders at Tillman Elementary School, a mostly white elementary school that had only one black student when I attended in the 1950 and 60s. Thornton ran unsuccessfully for the city council.

In the 1990s, when some Meacham Park residents worried about being annexed by Kirkwood, Thornton favored annexation. When some questioned Kirkwood’s redevelopment plan that replaced homes with Wal-Mart and Target stores, Thornton strongly supported the plan.

Those integrationist moves backfired in Thornton’s mind. The annexation led to stronger code enforcement and the beginning of his disputes with Kirkwood about parking his trucks near his home. Thornton told friends and relatives he also was bitter about the redevelopment plan because he didn’t receive the big, minority set asides on demolition contracts that he thought he had been promised.

By 2003, Thornton had dropped out of civic groups. He also was losing subcontractor jobs and had filed for bankruptcy. He was signing his letters “A free man” and railing about Kirkwood’s “plantation mentality” and “slave taxes.”

In early 2003, retired Kirkwood High School principal Franklin S. McCallie spent five months negotiating between his friend Cookie and city officials. McCallie had known Thornton for years, having attended his marriage to Maureen, also an educator.

McCallie has devoted his life to racial justice after seeing racism up close in his boyhood home of Chattanooga, where his family runs an elite private school. Three loose-leaf binders attest to McCallie’s mediation effort. But by May 2003, he admitted he had failed. The city had agreed to waive parking fines of tens of thousands of dollars, but Thornton said he couldn’t compromise his principles.

Later, McCallie heard Thornton attack the city council again, hee-hawing for three minutes in what he called “jackass-ese.” McCallie rose to say how disappointed he was with his friend’s behavior. Thornton still embraced him after the meeting.

A councilman on the receiving end of Thornton’s city council tirades was Paul Ward, the second African-American to sit on the council. Ward sees a parallel between Thornton and Kevin Johnson, the young Meacham Park resident sentenced to death for the 2005 murder of another white Kirkwood policeman, Sgt. William McEntee.

“The two men believed they had no recourse.” Ward said. “Their pain was greater than their respect for life.”

Ward and his brother Wallace, who served on the Kirkwood Board of Education, tried to help Thornton navigate the paperwork required of a subcontractor on the Meacham Park demolition jobs. Still, Thornton thought he was shorted on contracts, Wallace Ward recalls. “I told him to look at his contracts as found money,” Ward said. “But he couldn’t. He saw it as race, even though it wasn’t.”

Thornton told friends that a First Amendment suit he had filed without a lawyer would vindicate him and win millions. On Jan. 28, 2008 U.S. District Judge Catherine Perry ruled Kirkwood could remove him from meetings when he engaged in “virulent, personal attacks.” Joe Cole, a Meacham Park leader, had dinner with Thornton after the decision. He told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch he found a man defeated. “Everybody said he lost his brain. No, hate got into him. He couldn’t stop the hate.”

On Feb. 7, Thornton scrawled a note – “The truth will win in the end” – and headed to City Hall with a large caliber handgun. He killed an officer outside City Hall, took his gun and entered the council meeting just after the Pledge of Alliance, holding a placard as he often did during protests. Shouting “Hands in the Air!” 20 times, he corned his victims, murdered three city officials and gravely wounded the mayor. Two police officers killed Thornton in the chambers.

The day after the murders residents of Meacham Park gathered for two-hours in a meeting filled with such expressions of pain that it seemed impossible this was part of a time when a black man was on his way to be elected president.

Residents complained police had one set of rules for Meacham Park and another for the rest of Kirkwood. White youths who ventured into the neighborhood to see friends were suspected of buying drugs. Complaints to the city’s human rights commission went nowhere. The police chief’s well-intentioned attempt to reach out to Meacham Park had faltered. The redevelopment of Meacham Park was a land grab, some said, forgetting that Thornton had been one of its strongest proponents.

The Sunday after the shooting, the newspaper headlines talked about moving on, the healing process and the quick remodeling of the City Council chamber. City officials ordered a new coat of green paint to remind residents that this is a town of trees.

Thornton’s widow requested the funeral be held at Kirkwood United Methodist Church in the center of town to make the point that Thornton’s hometown was the greater Kirkwood community. Pastor David Bennett opened the church’s doors without a moment’s hesitation. “This is who we are, this is what we do,” McCallie remembers Bennett saying.

Mourners filled the church and spilled out the door. When McCallie said he hoped the entire city would work together “to make sure this never happens again,” the congregation, black and white, rose in spontaneous applause.

Mayor Mike Swoboda, seriously injured in the shooting, seemed at first to be healing. But by fall he was dead. At Christmas we remembered that our friend, with whom we played volleyball at the Kirkwood gym when we were 20-somethings, had done us a good turn the previous Christmas Eve. Our daughter-in-law from out-of-town had gotten lost jogging. She waved down a passing motorist for directions. The motorist was Mike, hurrying to the grocery store. “Get in I’ll take you home,” he said. “I know everyone in Kirkwood. I’m the mayor.”

We wrote a short thank you letter to the Webster-Kirkwood Times about how this only could happen in Kirkwood – never imagining what was about to happen.

The community healed better than Swoboda. The Community for Hope and Understanding held meetings across the city to talk about white privilege and racial understanding. Harriet Patton, the long-time leader of Meacham Park, recalled how a teacher ripped up a paper she had worked hard to write as a junior high student at Nipher because it was so good the teacher thought she must have cheated. Others recalled having to go to the kitchen door of the popular Spencer’s Grill to get served.

The U.S. Department of Justice issued a report recommending ways the racially divided community could unite. The city strengthened the Human Rights Commission. Meacham Park, the city and the school district partnered to start a Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration. And the city renovated Meacham Park Memorial Park.

Ten years after the shooting, Patton told the Post-Dispatch: “I have seen progress. A seed has been planted, it’s been watered. It is strong. Now, I’m looking for the bloomin’.”

Hand up, Don’t shoot

Hands up, don’t shoot never happened. The Justice Department and St. Louis County grand jury investigations proved that.

Officer Darren Wilson allowed a confrontation with Michael Brown to escalate when he should have de-escalated. Brown contributed to the escalation. He grabbed Wilson’s gun through the window of the squad car and fired it. After running away Brown turned back and charged Wilson who shot him dead.

It shouldn’t have happened that way. But it did and in the instant online explosion of social media that followed Hands Up, Don’t shoot became a national rallying cry.

But that isn’t what made Ferguson into this century’s Selma. It was the attention on police accountability, reform of prosecutors’ offices and court and bail reform.

The federal investigation found the Ferguson police department’s rampant unconstitutional practices fell heavily on blacks. All of the department’s police-dog bites occurred during arrests of African Americans. Ninety-six percent of those arrested for not appearing in court were black. Eighty-eight percent of all cases involving use of force were against black suspects. And blacks were far more likely to be searched than whites even though whites were more likely to be found with contraband.

Beyond that, the protests led to the realization that an invisible part of the American judicial system – municipal courts – was often abused by small towns that operated them like cash registers raising money for town operations. Citizens who never had committed a crime were locked up for having failed to appear in court to pay a fine. The result was lost jobs, lost apartments and wrecked families.

Brendan Roediger, a Saint Louis University law professor active in court reform, recalls deposing former Ferguson Police Chief Thomas Jackson and asking how many of the 10,000 people locked up in the Ferguson jail over a recent five year period were there after having been sentenced for a crime. “He said, ‘Oh yeah, it happened one time.” In other words, the other 9,999 people in jail were not there for crimes, says Roediger.

Here are some of the reforms that grew out of Ferguson:

- Ferguson fueled the Black Lives Matter movement and contributed to election of reform prosecutors here and across the country in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Kansas City and Chicago. Ferguson protesters led the campaign to elect Kim Gardner as St. Louis’ first black prosecutor, and Wesley Bell stunned the political world beating Bob McCulloch, the powerful prosecutor who had cleared Wilson in Brown’s death.

- Justice Department intervention in the operation of the Ferguson police department led to a consent decree requiring constitutional policing.

- Missouri passed a new law limiting the use of deadly force to instances where police had probable cause a suspect posed a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others.

- ArchCity Defenders, a public interest law office that rose out of obscurity, won a $4.7 million settlement from Jennings over operation of its municipal court as a modern-day debtor prison; similar lawsuits against Ferguson, Florissant, St. Ann, Edmundson, Normandy and Maplewood linger in court.

- The Missouri Legislature enacted a reform limiting the amount of municipal fines that could be used for a town’s expenses, gradually forcing some small municipal courts out of business.

- The Missouri Supreme Court ordered changes in municipal court procedures. Later, in 2019, it issued new bail rules limiting how long a defendant can be detained without a hearing and requiring courts to balance community safety with the defendant’s ability to pay. New procedures for more prompt hearings and ankle monitoring have led to a 20 percent reduction in jail population in the past year.

- St. Louis. Post-Dispatch columnist Tony Messenger’s revelations about reincarcerating former prisoners for failing to pay their board bills – the cost of food and lodging during an earlier jail stay – shocked the legal system and general public, leading to reforms.

- Greater scrutiny of police conduct after Ferguson led to the 2017 prosecution of a former St. Louis Police Officer Jason Stockley for killing Anthony Lamar Smith at the end of a police chase. Stockley had been recorded as saying during the chase he was “going to kill” Smith “don’t you know it.” A judge acquitted Smith prompting days of Ferguson-style protests in downtown St. Louis.

- During the Stockley protests, St. Louis police used the unconstitutional tactic of “kettling,” which is trapping protesters in a closed space, tear gassing them and arresting them. White officers also beat up an undercover black officer during those protests, leading to prosecutions.

- Gardner angered the white police union with her list of 59 police officers who could not bring criminal charges because they had credibility problems from past cases or because they had made racist social media posts.

- When Gardner sought a new trial for Lamar Johnson, who has spent 25 years in prison for a murder that Gardner’s Conviction Integrity Unit says he did not commit, she ran into a solid wall of opposition from the white legal community. Misconduct by the prosecutor and police payments to a false witness contributed to the unjust conviction, she found. But a judge and Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt claimed Gardner lacks the power to ask for a new trial for a prisoner her office wrongfully convicted. People would lose faith in prosecutors, Schmitt said. The Missouri Supreme Court will decide who is right.

Thomas Harvey, who led ArchCity Defenders during Ferguson, had been trying to expose petty municipal corruption for years before Brown’s death. But he couldn’t get people to pay attention to the big impact minor fines, small town municipal courts and abusive police traffic stops could have on people’s lives.

It took the death of Michael Brown to finally attract the nation’s attention to this racist injustice that had been hidden in plain sight, along with all of the other vestiges of slavery and segregation.

William H. Freivogel is the publisher of Gateway Journalism Review. This story is published in the spring 2020 print issue of the magazine.

Disclaimer: GJR’s special issue on the history of slavery, segregation, and racism in our region was produced with the help and financial support of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.