A St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter listens through a closed courthouse door and tweets what he hears. The judge finds the eavesdropping reporter in contempt and orders him to write letters of apology. He is also to “participate in an educational program with court staff” on the First Amendment and right to a fair trial.

The case file disappears from Missouri’s electronic case filing system only to reappear after the newspaper and prosecutor discover it missing. A court spokeswoman, herself the former Post-Dispatch editorial editor, issues a statement on the contempt case that rankles her former colleagues who call it sanctimonious. The Post-Dispatch editor angrily points out the court file would still be missing but for the newspaper’s work and adds “matters that should be conducted in open court…are not.”

This may sound a little like a scene from The Front Page, but it is a modern story that pits a free press and open justice against privacy and the right to a fair trial.

The hard-charging reporter who eavesdropped and tweeted is Joel Currier, who has been covering law enforcement and the courts for the paper since 2005. The director of Strategic Communications for St. Louis County Circuit Court is Christine Bertelson, former Editorial Editor of the Post-Dispatch. Bertelson’s criticism of Currier drew the attention of the Post-Dispatch’s storied columnist Bill McClellan, who suggested in his gentle but unmistakable way in a Sunday column that Bertelson and the judge who found Currier in contempt, Ellen Ribaudo, were “being self-important.”

Ribaudo had said Currier proved untrustworthy. “Trust takes years to build, seconds to break, and forever to repair.” McClellan turned the tables on the quote. The judge “was referring to pushy reporters,” wrote McClellan, “but she could have been talking about courts that prefer to operate behind closed doors. What we can’t see, we don’t trust.”

No Post-Dispatch lawyers present

The dispute began April 12 when Ribaudo closed her courtroom during a hearing on whether Antonio Taylor was mentally competent to stand trial. Taylor was charged with shooting Ballwin Officer Michael Flamion in 2016, leaving him paralyzed from the neck down.

Shortly before the hearing, the public defender asked it be closed. Currier objected and Ribaudo allowed him to speak. But she rejected his argument without hearing from Post-Dispatch lawyers.

First Amendment experts familiar with the case say the judge’s failure to give the paper’s lawyers a chance to make their legal case could be a deficiency in the judge’s handling of the case.

Court proceedings are presumptively open both under U.S. and Missouri Supreme Court decisions.

In a 2001 case brought by the Post-Dispatch, the Missouri Supreme Court wrote that the presumption of openness was based on the longstanding belief that, “Justice is best served when it is done within full view of those to whom all courts are ultimately responsible – the public.”

Ribaudo asked Currier during the April 12 hearing to come up with an alternative way to protect the confidentiality of psychiatric evaluations performed for the competency hearing. When he didn’t come up with one, Ribaudo closed the hearing and told him to leave.

Ribaudo relied on a Missouri law that requires psychiatric evaluations for competency hearings to be confidential. However, Ribaudo critics point out the law does not require the hearings to be confidential – just the reports. Court regulars say that competency hearings in St. Louis city courts and federal courts often are open.

Currier left the hearing on Ribaudo’s instruction but listened at the door and started tweeting. His first tweet, which still is posted, announced the closure and acknowledged his “very unlawyerly” argument to the judge.

Currier followed that with about 10 more tweets, now deleted, including the one that Bertelson quoted in her press release in June. That one said, “After Judge Nellie Ribaudo closed courtroom to the public — i.e. one lone reporter — I spent most of the afternoon with my ear to the door live tweeting details. (Glamorous life of a print journalist.) Wouldn’t have bothered tweeting had I been allowed to stay. #democracy.”

Ribaudo moved to hold Currier in “indirect criminal contempt.” Ribaudo brought Currier into court May 9 to discuss the contempt case. The Post-Dispatch thought the issue was being resolved in discussions between the court and Joseph E. Martineau of Lewis Rice. Currier and the paper apologized for the eavesdropping and what had started as a criminal contempt became a civil contempt agreement. Then came a June 4 press statement that Bertelson posted on social media, angering the Post-Dispatch editors.

Post-Dispatch editor Gilbert Bailon’s pique at Bertelson’s statement was evident in a statement he released, in turn, to the Riverfront Times.

“The quality of Joel’s reporting and ethics are beyond question. On this occasion, he was wrong and he admitted he was wrong, submitting a letter of apology to the court long before any order that he do so.

“His error was borne of frustration by occasions reported in this newspaper and the Riverfront Times, where matters that should be conducted in open court and records that should be publicly available are not. In fact, in the very same case that prompted Joel’s actions, the court order finding the defendant incompetent to stand trial and the entire case file was closed to the public. It was made public only after disclosure by the prosecuting attorney and reported in the Post-Dispatch.”

Bertelson said in a telephone interview Monday that her press release was merely intended to report news, not stir the waters.

“To my mind this is news. A reporter being found in contempt doesn’t happen every day. I don’t think i was throwing gasoline on the fire. I was being very measured and quoting from the decision. Judge Ribaudo said from the beginning, ‘I’m not mad at Joel. I want this to be an opportunity for education – a teachable moment….’

Missing files

On May 21, as the contempt issue was playing out, Ribaudo finalized her determination that Taylor was not fit to stand trial and she officially committed him for six months. But none of that information was made public and the entire case file disappeared from Case.net. It reappeared after the prosecutor commented and the Post-Dispatch reported on the judge’s action and missing file.

Bertelson said in the interview that Bailon was not correct in saying it was the newspaper story that resulted in the file being made public again. Bertelson said that when Ribaudo learned that the clerk had taken down the file, she ordered the public portions restored. The court has asked the Post-Dispatch for a clarification of Bailon’s comment.

But Bertelson acknowledged in the interview the court is still looking into why other cases involving competency determinations also have disappeared from Case.net.

“That is something that Joel has been concerned about for a long time that predates me. I don’t understand why that happens and am trying to figure that out. I’m trying to get an answer so that I am in the position to explain it. I don’t know who makes those decisions, if it is a judge or a clerk.” In the Taylor case it was a clerk who had mistakenly taken down the files.

In emails to Bertelson on Monday, Currier identified other cases that have disappeared from public view, including that of Robert E. Britt, a retired county counselor, who was declared incompetent to stand trial for killing his wife of 54 years, Georgia. Over the past weekend, the file of Haven Sooter also disappeared from Case.net, Currier’s email said. Sooter was recently found competent to stand trial in the death of Kathleen “Kay” Koutroubis, an innocent victim of a 2016 drag racing accident on Lindbergh Blvd. in Frontenac. Sooter’s file reappeared on Case.net later Monday.

Bertelson said she knows from her days as a reporter that the journalists and judges see their jobs much differently.

“I remember trying to read documents upside down on a desk,” she said. “But the court has a different mission. It has rules it must abide by. Reporters want to get the story by hook or crook and get it first. Rules are made to be bent. Reporters aren’t particularly rule followers. Judges tend to be….It is important to communicate across disciplines….It’s clear to me that Joel crossed the line and knew he did and did it because he is pissed off that the court has been secretive.”

Publisher’s Note:

This reporter has multiple conflicts in this story. Currier and I are teammates on Media Circus, the former Post-Dispatch softball team. I spent a night in the emergency room with him when he broke his nose going out from short to catch a fly ball.

Bertelson was my boss on the editorial page. I was her deputy for nine years.

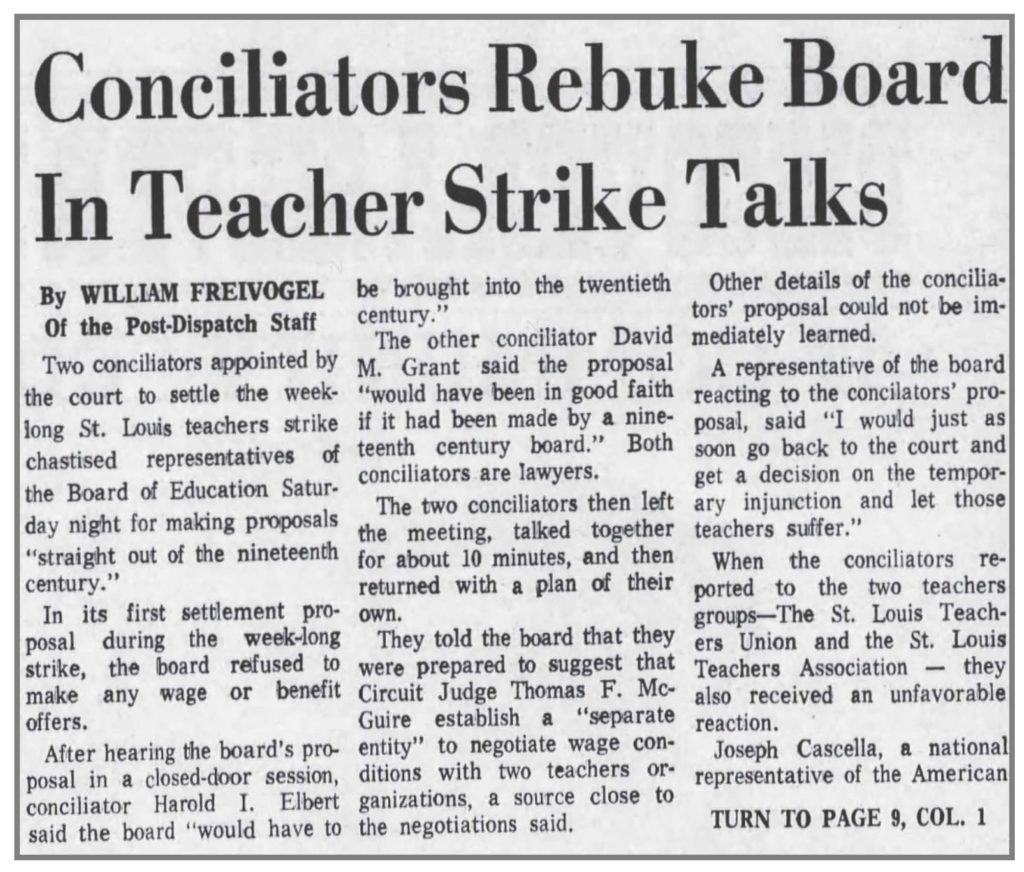

And, 46 years ago I eavesdropped at the door of a court-ordered negotiating session during St. Louis’ first teachers strike. St. Louis’ blue-ribbon School Board had refused to make settlement offers because the strike was illegal. Judge Thomas F. McGuire ordered the board and union to negotiate with mediators.

The setting was the old Jefferson Hotel. All of the reporters were removed from the meeting. I stood at the closed door and took notes on everything I heard. I had a nice front page story the next day quoting the negotiators saying the School Board’s proposals were “straight out of the 19th century.”

McGuire called me into his chambers after the story ran and asked how I had gotten the quotes. I told him. He laughed and was generally pleased that the School Board’s old-fashioned ways had been called out on page one.

No contempt of court for me or letters of apology. The editors were pleased with my aggressiveness. I got a pat on the back. Those were the days before newspapers had ethics policies and before reporters could tweet themselves into trouble instantaneously.

A lawyer friend of mine reminded me Monday that if reporters want to hold public officials accountable, we need be accountable ourselves and cut out roguish behavior. I basically agree but can’t help but notice that media credibility was far higher half a century ago than today.

William H. Freivogel is the publisher of Gateway Journalism Review and a member of the Missouri Bar. He specializes in the First Amendment.