When Kimberly France, a descendant of free African-American pioneers, first approached Toni Craig to help piece together her family’s history in a southern Illinois community called Africa, Craig wasn’t sure she was up for it.

Craig already had spent years assembling and telling the stories of the community of Africa, which is located 120 miles from St. Louis.

France and Craig are both descendants of Black and racially mixed pioneers who helped settle the Northwest Territory, including Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin and a portion of Minnesota. The original settlers were either born free or became emancipated.

Africa descendants like Craig kept records, artifacts and photos, telling the histories of these settlements and the people who lived there, passing it down to future generations. Their stories and impacts on American history have mainly gone unacknowledged for over a century. That history is now being preserved and curated through the work of their descendants.

Some of those records and oral histories don’t tell the whole story, and the people who lived the history and know it best have long been dead. Some descendants also have been adamant about not perpetuating tales that cannot be proved or fail to tell the whole story. And some find some value in the legends.

That has made it difficult to tell the story of Africa, though Craig tried, for years, primarily through lectures at the Williamson County Historical Society.

Craig had retired mostly from her volunteer work when she ran into France at an annual family reunion in late May at Locust Grove Cemetery in rural Williamson County.

France reached out to Craig, wanting to know more about a place she knew as “up in the country” and Locust Grove Cemetery. The area, what some would call a “ghost town,” was also known as “Africa,” “Little Africa,” “Locust Grove,” “Skeltontown,” and “Fancy Farms,” according to historical sources and local tradition.

Craig still lives there — on land that has been in her family for 250 years.

“Her little spark was enough to start my fire,” Craig said of France.

According to Craig’s grandmother Ary Dimple Bean’s records, Locust Grove was once a self-sufficient community of about 40 families and 150 people after the Civil War. Collectively, they owned more than 500 acres.

It is now farmland scattered with homes and old cemeteries sitting among patches of trees.

The two churches and one integrated school are gone.

The women are likely distant relatives through marriages from generations ago. However, Craig and France are more connected by the place of Locust Grove than their blood relation. “She’s a bridge in history for us. Renewed how I feel about it because I wasn’t even going to touch it,” Craig said.

Finding Africa

Historians and journalists from the 20th century tell the origin of Locust Grove as a community created by the McCreery family who settled in Illinois around 1816. The brief version states that this family gave land to the people they enslaved and freed them.

In the version published by West-Frankfort’s newspaper, The Daily American published in 1971, this was a place where enslaved people could negotiate with their owners a wage that they could use to buy their freedom.

According to regional and national historians, this was not unusual. For example, this situation also occurred in the Salt Works in nearby Saline County.

A more comprehensive, in-depth historical account corroborated across multiple sources of information is Fancy Farms where slave owners brought their enslaved people to emancipate them before the Civil War. Credit goes to the McCreery family for establishing Fancy Farms, and subsequently, Locust Grove.

While the McCreery family did bring enslaved people in 1816 to Illinois, they left when the state was admitted to the union as a “free” state two years later. John McCreery, the father, took the enslaved people to Missouri.

In her book Pioneers and Places, Barbara Hubbs writes that McCreery took most of the enslaved people to Missouri, and the ones he didn’t, he freed.

According to History of Williamson County, Illinois, by Milo Erwin, published in 1879, John’s son Alexander McCreery was against slavery. He traveled to Missouri to buy Richard and Cillar Inge from his father. Then, Alexander took the Inge family back to Illinois, where he freed them.

Hubbs tells a slightly different story: John McCreery died in Missouri, and the people he enslaved were “inherited” by his son, Alexander.

Alexander took the enslaved people back to Illinois, where he freed them. While in Missouri, he also bought an enslaved woman whose husband was one of the enslaved people John McCreery owned. That was Richard and his wife, Cillar Inge. Once freed, Inge bought 80 acres in Locust Grove.

While this oral tradition is likely true, it leaves out important information otherwise obtained by other sources.

A typed history explains Craig’s ancestors’ journey to Locust Grove, written by her grandmother, Ary Dimple Bean. She was born and raised at Locust Grove.

According to Bean, residents at Locust Grove were ex-revolutionary, buffalo, or civil war soldiers who received land grants from the government. Families also descended from formerly enslaved people.

The first settler of Locust Grove was an African-American man who was a runaway slave. She was told this by her mother and the other residents in that community, by Bean’s account. It is unknown if he came from a plantation in Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, or Tennessee. He was known as Skelton, hence Skeltontown, which is in the northeast corner of Williamson County.

In the same document, Bean outlines her lineage and her ancestors’ journey to Locust Grove.

Bill Martin enslaved Bean’s maternal great-grandmother in Tennessee.

“He took her for his mistress after selling her husband and one of her two sons (because she at first refused him),” Bean wrote.

To Susan and Bill Martin, five children were born. After the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, Bean wrote that Bill gave Susan forty dollars and sent her north with their children.

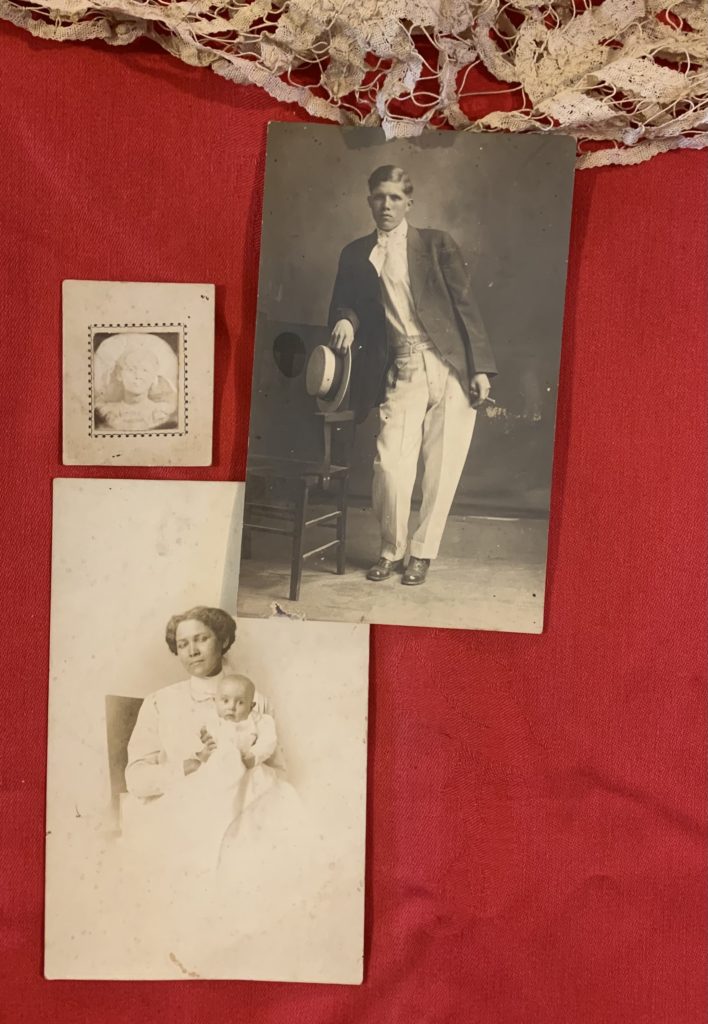

Craig, Bean’s granddaughter, has the pouch and glass-plated photographs sent with her ancestor on their journey to Illinois. When Susan and her children arrived at Locust Grove, she used the remaining money to buy 40 acres. One of her sons later increased their property to 200 acres.

Bean’s other grandmother, Ara Ann Brooks, was born to a white woman and a Black man who lived in Meridian, Mississippi.

“Elizabeth Brooks was a widow who sympathized with the slaves and taught them secretly at night. She was also a midwife and frequently tended women during childbirth. Having given birth to a negro child, she lived in fear of having it stolen or sold down the river as a slave,” Bean wrote.

Ara Ann’s father was a domestic enslaved man in Elizabeth’s father’s household, according to Bean. Elizabeth hid in corn stalks with her daughter and other enslaved people hiding from slave traders looking for them.

Ara Ann married William Harris, a man of African and Native American ancestry. According to Bean, they married in Alabama and did not want to live in a slave state, so they migrated to Illinois.

At the Tennessee River, they were refused passage because they were seen as runaway enslaved people. As a result, Elizabeth Brooks, Ara Ann’s mother, had to pretend William and Ara Ann were her indentured servants for the remainder of the journey. When they crossed the Ohio River at Shawneetown, they learned of a little African American community a few miles west, Locust Grove.

William Harris died after fighting in the Civil War in the Union during the winter. Ara Ann Brooks then married Presley Martin.

The primary occupation at Locust Grove was farming. Tobacco and castor beans were the main crops they sold at Marion, Carbondale, and Galatia.

“They always took a white man with them to market because the buyers would not give a Negro a fair price,” wrote Bean, who attended Southern Illinois University when it was formerly Southern Illinois Normal University and graduated in 1924. She later taught school.

Each family raised their cotton and carded it for quilts. They grew their food, canned it, stored it, and milled their corn for feed and meal. Another of Bean’s grandmothers was a widow with a family of 10. She raised sheep, and taught her daughters how to card, spin, and weave with a loom.

For recreation, church festivals happened every two weeks that nearly everyone in the community attended. There were also ‘play parties’ where people played folk music and danced Irish dances.

According to records scribed by Bean or given to her by community elders, other families recorded to have lived at Locust Grove included the Stewarts, Stewards, Whites, Fears, Skeltons, Allens, Hawsleys, Harrisons, Harrises, McCreerys, Beans, Wesleys, Clemons, Chavises, Williams, Grays, Longs, Hollands, Porters, Pattons, Youngers, Hargraves, Finches, and Littlepage’s.

In 1937, only seven families remained at Locust Grove.

“Most of those living there have radios, gasoline washers, and cars, and go to the nearest town two or three times per week,” Bean wrote. “The old residents like to sit and talk about the modern way of doing things and wonder what the world is coming to.”

‘The hope of your calling’

By the time France, who grew up in Carbondale, traveled the 35 miles to Locust Grove for funerals and family reunions in the 1960s and 70s, the Locust Grove church and cemetery were all that was left.

Her grandmother, Madelene Allen, raised France, she said. Allen was the daughter of Henry Finas Allen and Matilda Stewart.

Stewart’s father, Timothy Stewart, served in the Civil War in the 29th Colored Infantry, among other Black soldiers from sister communities in neighboring counties.

Henry was the grandson of John and Myra Allen, who were also free African American pioneers from North Carolina. They first settled in Lakeview, another African American settlement, and then arrived at Locust Grove around 1855.

A family legend written by Brent Hope Jennings, a descendant of the Allens, and Rebecca Jennings in The Allen Chronicles tells a story about forbidden love between an Irish tobacco farmer’s daughter and one of the domestic enslaved men. In the legend, they escape North Carolina to Illinois.

According to southern Illinois historian Darrel Dexter’s genealogical research, John Allen was already free in North Carolina. He showed up in the 1850 census as a laborer. John and Myra had eight children — one of them, James Randall, was Henry’s father. Marriage records show Myra and John Allen separated between 1850 and 1860.

James’ brother, Irvin, moved back to Lakeview around 1865.

Lakeview is thought to be the state’s oldest free African American settlement because of its proximity to the Saline Salt Works. It was officially established in 1838 by the Taborn family.

Both communities established churches, cemeteries, and traditions like serving in the military and annual memorial day celebrations. They also practiced naming children after well-revered family members, resulting in people sharing names or going by nicknames.

According to American historian Anna-Lisa Cox, author of Bone and Sinew of the Land: America’s Forgotten Pioneers and the Struggle for Equality, the Salt Works in Saline County were among the earliest industries developed by the newly formed United States Government.

Enslaved African and Indigenous people and white indentured servants worked here together.

Emancipation records and free Black registration papers show numerous enslaved men and women used the opportunity at the Saline Salt Works to negotiate a wage that they used to buy their freedom and their family members’ freedom.

Cox calls them “freedom entrepreneurs.”

One of those entrepreneurs was Cornelius Elliott.

Elliott was an enslaved person owned by Timothy Guard, a leaseholder of the U.S. Saline Salt Works. Elliott bought his and his family’s freedom.

According to public records, he was also the first person to buy land from the federal government in 1829 in Gallatin County. He purchased 80 acres for $1 each.

Elliott later settled the African-American community called Grayson, south of Eldorado.

Although Illinois was often called “the Promise Land” by runaway enslaved people and Free African Americans, the southern Illinois region geographically and culturally resembles the upland south than the prairie region to the north.

During the 19th century, Illinois passed laws banning free African American settlement, interracial marriage, and the assemblage of African Americans, including for religious worship.

In addition to political discrimination, as African Americans flourished, they were targets for violence and kidnappings. According to Milo Erwin, in 1872, there were 130 members of the Ku Klux Klan in Williamson County.

Before she investigated her family history, France did not fully grasp what it took for her ancestors to create an “oasis of our own” in a state and country poisoned with prejudice, she said.

“I can put it in context with the wars and the status of blacks in this country, and how things have changed,” France said. “Because while all these things were happening in the country, these folks managed to carve out a wonderful life and establish rich traditions. And, give us a legacy and an inheritance that I just really believe is priceless.”

Historical context is critical to understanding the significance of African American settlements as prosperous as they were in this region and the country.

According to Cox, after the American Revolution, some people had a common sentiment that the slave trade was opposite to the ideals laid out in the constitution, and it could not work.

The Northwest Territory, which practically doubled the nation’s size at the time, was this vast land where slavery was banned. As slave owners freed tens of thousands of enslaved people, those newly freed Americans and the free-born Black Americans traveled west to settle this new American territory.

These pioneers successfully obtained land in the 18th and 19th centuries, despite their fellow Americans stripping away their constitutional rights.

John Ellis was one of these pioneers.

Ellis was a Black Revolutionary War soldier who was a private in the 10th Regiment of the Continental Army of North Carolina. He settled in southern Illinois between 1820 and 1830. He is buried in New Dennison, another pre-Civil War African American community in Williamson County.

But that historical context was rarely mentioned by white writers in the 20th-century.

The lack of documentation in the past has implications today as people like France put the puzzle pieces of their ancestry back together.

“The important thing to do is to tell these families’ stories because I feel, regardless of how Africa came to be, the people that deserve the credit, the recognition, and the acknowledgment are the families,” France said. “What I realized about oral history and, particularly about black folks, is the story you tell is the story you’ve been told. And if you’ve been told all your life that you’re descendants of slaves, that you’re not citizens, and that you’re less than, that’s the story that you internalize. That’s the story you believe about yourself.”

France credits her successes to her rich family traditions established by the Allens in Lakeview, which continued in Locust Grove with the Stewarts.

Craig and France’s ancestors left just enough so their descendants could know from where they came. And France believes she owes it to her ancestors to continue telling the story of these communities to the younger generations.

She strives to create a “Little Africa” foundation that can pool enough resources to rebuild the church and preserve documents and artifacts. She’d also like to see it become a heritage site. In the community of Lakeview, descendants have similar aspirations for preserving their history.

For members of these communities, their history is more than just facts.

It is an inheritance, the peace of knowing who you are.

“There’s Bible scripture in Ephesians that talks about the hope of your calling and the joy of your inheritance. So Paul’s saying, you know, I hope that you have that. Like, I wish that and pray that for you. And I feel like, for the first time, I understand what that is,” France said. “And I feel that I have it because my ancestors gave it to me.”

Amelia Blakely was raised in Anna-Jonesboro, Illinois. She reported from Anna and Nashville, Tennessee. She graduated from Southern Illinois University Carbondale and was a 2020-2021 Campus Consortium Fellow with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting in Washington D.C. Blakely is currently an outreach core member for the Illinois Student Assistance Commission. You can find her on Twitter @AmeilaBlakely.