Anatomy of Stripped for Parts: American Journalism on the Brink

By Rick Goldsmith © 2023

In 2018, hedge funds had been scarfing up newspapers right and left for more than a decade. But outside of a handful of journalists covering the newspaper industry, no one knew anything about this new brand of media moguls: who they were, why they were buying into a declining industry, and what their plans were for the newspapers they were collecting by the dozens.

Until the April explosion that became known as the “Denver Rebellion.”

That spring I had been in discussion with the great journalist Bill Moyers about doing a film project together. He knew my work and of course I knew his. We discussed a possibility or two, but nothing quite crystallized, and I thought that was the end of it. But a few weeks later Moyers sent me an email: “I’m at the barber shop right now but when I read this I thought: Here’s a film only Goldsmith would take on. I’ll call you when I get home.” The email had a link to an article by Nieman Lab’s Ken Doctor about the hedge fund Alden Global Capital that was “making so much money wrecking local journalism it might not want to stop anytime soon.”

Three things from the article jumped out at me. First was the notion that the profits were to be made by “wrecking” journalism, rather than practicing it. (Why?) Second was the revelation that money could be made from an industry seemingly in collapse. (How?) Third—and this is what hooked me—was the fact that newspapermen and women in Colorado were apparently in open revolt against their own publisher. (Now that’s news!)

I’ve been a news junkie all my life. My first feature documentary, begun in 1989, was on George Seldes, a gadfly former foreign correspondent and then outspoken critic of America’s mainstream press. I interviewed him when he was 98, and he regaled me with stories on how General Pershing, Mussolini and his own newspaper publisher, Colonel Robert McCormick of the Chicago Tribune tried to suppress, change or censor his stories. A later film I co-directed, on war-planner-turned-whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, documented the decision-making inside The New York Times, in the face of threatened government legal action, of whether to publish a top-secret government document, the so-called the “Pentagon Papers.” It was one of America’s press’s finest hours. So mine has been a love-hate relationship with the news media: adoring but critical.

I relish interviewing journalists. They tend to be sharp evaluators of the events of the day. They put events into context. Smart, succinct, good story-tellers. And what made this “Denver Rebellion” thing unique, they were not only covering the news, they were making news—quite a turnabout for members of the mainstream press. Seldes famously wrote: “The most sacred cow of the press is the press itself.” The ones I talked to had no compunction about speaking out or risking their jobs.

I interviewed more than a dozen working reporters and editors, most of whom worked for newspapers that had been, or would be, gobbled up by Alden Global Capital. The Denver Rebellion was fresh in their minds, so the responses to my questioning were heartfelt, candid and passionate. Their memories were fresh, the specifics sharply-detailed.

Greg Moore, former editor of The Denver Post during the time of the Alden takeover, offered vivid and sometimes emotional accounts of his dream job turning into a nightmare. After he finished one such account of an event I’d researched, I said to him, “I never heard that story before,” and he looked at me for a second before saying, “I never told that to anyone before.”

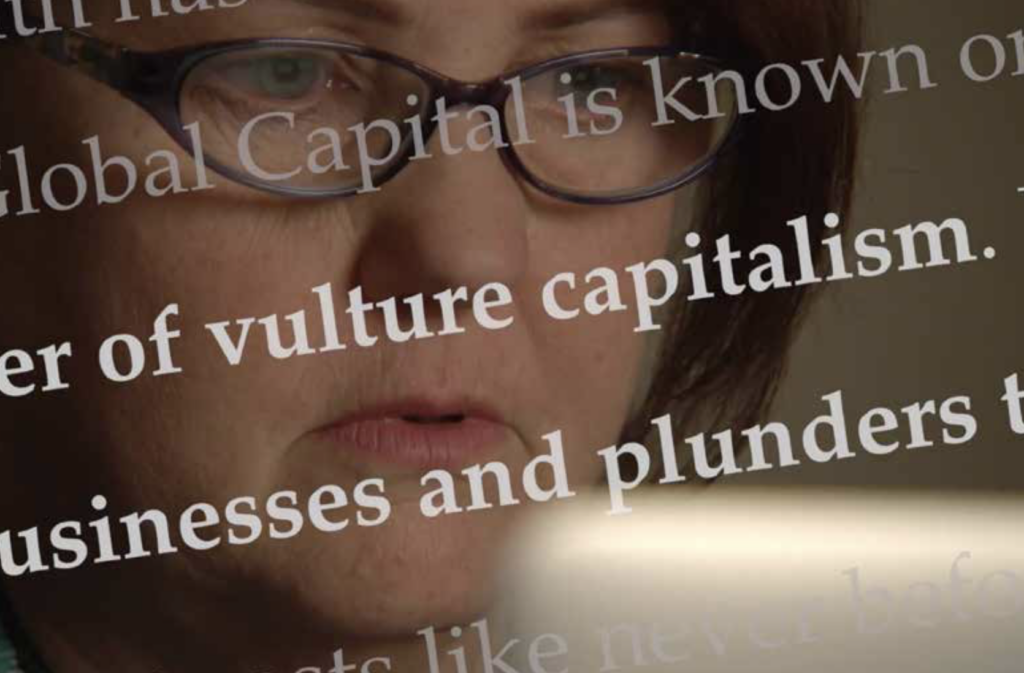

Julie Reynolds was the subject of a half-dozen interviews, one of them in front of her “crazy wall” of photos, post-its and arrows, like you see on a TV police drama. Julie did the heavy work of investigating Alden Global Capital, about whom she wrote more than 100 articles, uncovering facts, unraveling shady hedge fund business practices, and providing her fellow journalists at Alden papers—first through the NewsGuild’s website, later in publications like Newsweek, The Nation, The Intercept—the raw materials for their rebellions.

Chuck Plunkett, Denver Post editorial writer, spoke poignantly about his agonizing decision-making process before writing the riveting editorial that rocked the journalism world in April, 2018.

When Alden’s plundering reached Tribune Publishing, Gary Marx and David Jackson of the Chicago Tribune welcomed my request to record their stories, even as they were being threatened with firing for sending to The New York Times an op-ed outlining their fight with Alden. Gary returned to me again a year later, by Zoom (during Covid), impassioned as ever, shortly after discovering that a Swiss billionaire had read his Times story, been moved by it, and had decided he would try to out-bid Alden. “That’s your dream, that someone reads what you wrote, and acts on it.”

Dave Krieger’s dramatic standoff with his bosses at the Boulder Daily Camera was still fresh in his mind and his heart, after he’d taken a stand that was true to his journalistic principles. Having suffered the consequences of his actions, Dave reflected, “Did I go too far? I’ve never been so sure in my life that this was the right thing to do.”

Penny Abernathy was my guide through this journey. A giant in the journalism world for her extensive studies on “the new media barons,” “news deserts” and “ghost newspapers,” she challenged me on whether I had “the facts,” or was just re-stating common wisdom. She wanted to make sure I got it right.

Margot Susca, in the midst of composing her book Hedged: How Private Investment Funds Helped Destroy American Newspapers and Undermine Democracy (due to be published in early 2024) gave of her time and wisdom to help me get the context correct.

I approached Alden’s two principals and founders, Randall Smith and Heath Freeman. But they gave me the same cold shoulder that they typically gave reporters who approached them. I got as far as a return call from Freeman’s PR representative, but otherwise stone-walled me.

My goal in making this film was less to expose Alden Global Capital to the world—the above-mentioned journalists here, collectively, and others, did that far more completely than I could have hoped to do—and more to give the film’s audiences a feel for these men and women, who risked their reputations and/or their livelihoods, to save, re-invent, and rebuild journalism. Each of them believed in their own profession, as one that serves as the lifeblood of democracy. The interviews were enriching. I felt honored they trusted me enough to let me into their lives, to answer my questions, and to bare their souls.

I consider “Stripped for Parts” their collective story, and as important as the thousands of stories they have written over their careers, so that the rest of us can understand more completely the complex social and political events that swirl around us. I hope my film does them right.

Rick Goldsmith has been producing and directing documentary films for four decades, with his most acclaimed films focusing on journalism: Tell the Truth and Run: George Seldes and the American Press (1996) and The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers (2009), both Academy Award nominees for Best Documentary Feature. Stripped for Parts: American Journalism on the Brink was just completed in October, and has its Midwest premiere in St. Louis on Nov. 11, 2023.