Writing about Marie Antoinette, Judith Thurman commented in a 2006 article in the New Yorker that the woman famous for a remark she never uttered (“Let them eat cake”) is “periodically reviled or celebrated.” The same could be said about the media’s treatment of Hillary Clinton since she stepped into the national limelight as Bill Clinton’s wife during his 1992 bid for the presidency.

Writing about Marie Antoinette, Judith Thurman commented in a 2006 article in the New Yorker that the woman famous for a remark she never uttered (“Let them eat cake”) is “periodically reviled or celebrated.” The same could be said about the media’s treatment of Hillary Clinton since she stepped into the national limelight as Bill Clinton’s wife during his 1992 bid for the presidency.

Now that she is campaigning for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination, many publications and websites devote much of their coverage to one or the other of these familiar approaches. Recent opinion pieces in the online publications of the liberal New Republic and the conservative Washington Free Beacon provide a sort of “comfort food,” the first for Clinton admirers and the second for Clinton detractors.

But neither provides much food for thought based on solid information, history and context.

“The Real Democratic Primary: Hillary Versus the Media” by Suzy Khimm was posted on the New Republic’s website on May 22. This headline suggests something new — that Hillary is running against the media more than the pack of potential Republican candidates. But in fact, Hillary’s relationship with the press is old news. Ken Auletta described her difficulties with the media in the New Yorker on June 2, 2014, observing that “the media can’t stop discussing her” and are “desperately casting about for something new.”

The “new” element in Khimm’s story includes interviews with 30-or-something-year-olds in Arlington Virginia, a Washington, D.C., suburb she labels “Hillaryland.” Her first interviewee is 29-year-old Beth Lilly, a policy lawyer who remembers the hullabaloo created by Clinton’s Marie Antoinette moment in 1992, when she said: “I could have stayed home and baked cookies and had teas, but what I decided to do was fulfill my profession.”

Lilly, who would have been about six years old in 1992, recalled that the coverage of the cookie escapade “was just so absurd.” In examining the questionable finances of the Clinton Foundation, Khimm also quotes Lilly as saying, “So her foundation took money. It’s kind of what foundations do.” Khimm could have suggested to Lilly that media coverage has focussed not on what foundations do, but on where some of the millions taken in by the Clinton Foundation came from and how they were doled out. (As in “Clinton Award Included Cash to Foundation,” the New York Times, May 30, or earlier, “Cash Flowed to Clinton Foundation Amid Russian Uranium Deal,” in the same paper on April 23.)

When Khimm points out that Clinton’s young Arlington supporters view the media as “trying to drag her (Hillary) down,” she does not ask them for examples. Khimm does not tell her readers which dust-ups in Clintonian history qualify as “scandals” and which as “pseudo-scandals,” and none of the people she interviewed made the distinction for her.

According to Khimm, Clinton’s young supporters no longer blame Republicans or right-wing conservatives for the coverage she is receiving. It’s the media’s fault. One supporter says: “The media are bringing these allegations and these scandals up to see if anyone else in the Democratic party will emerge as a strong candidate and they can go head to head…That sells if you put that out, it sells. It’s them trying to tailor the election to their own needs, rather than what the election is.”

And that’s what the article is meant to reveal, that Clinton’s well-earned path to the White House is not impeded by those Republican bumps in the road, but by roadblocks put up by the media.

Khimm’s article is of, by and for Washington insiders, deeply divided, seeing the world with us v. them blinders. Khimm accepts Clinton’s climb as “the ultimate Washington success story,” never asking citizens in West Virginia or Kansas if that translates into a national success story for them.

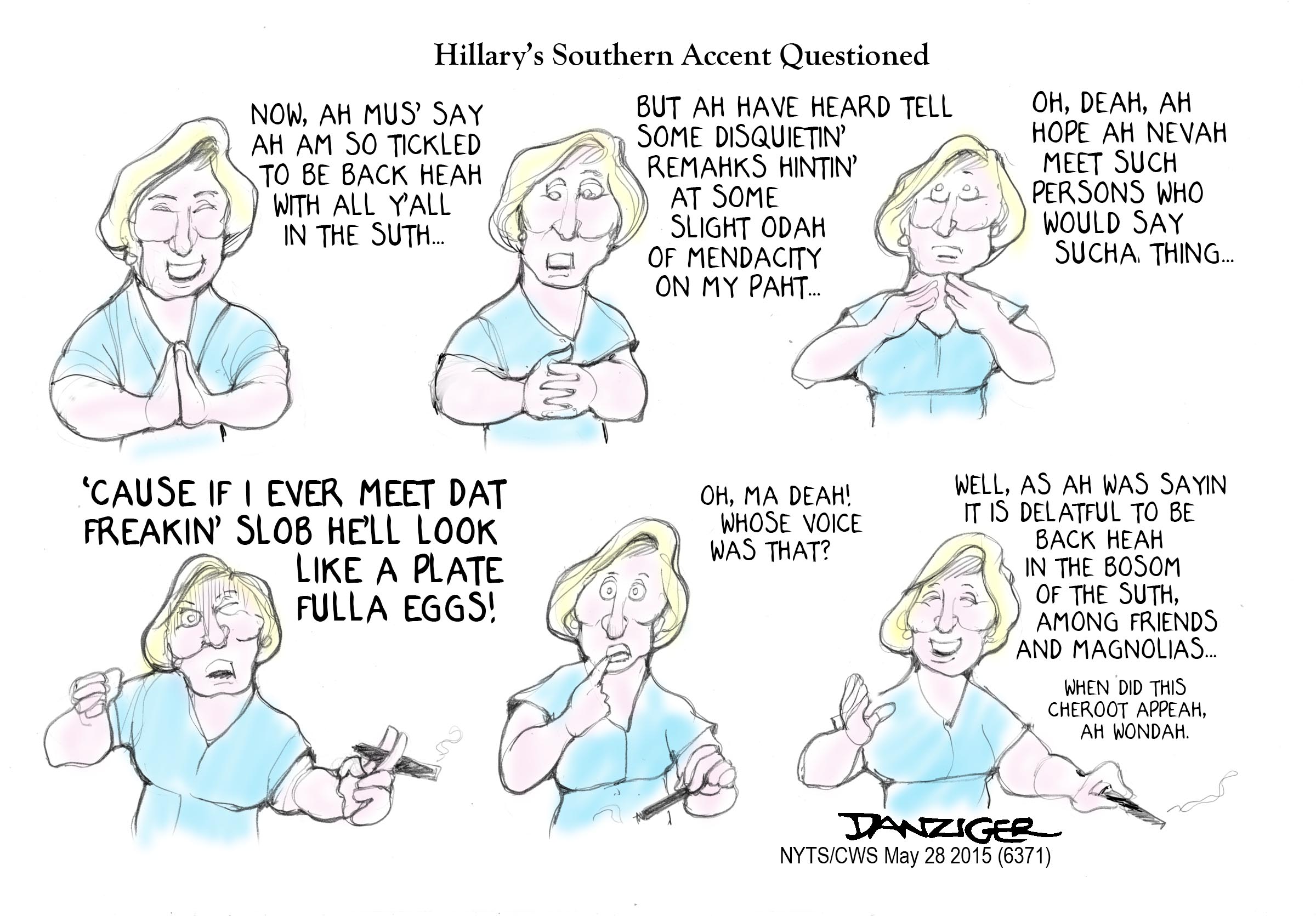

A Clinton as Marie Antoinette piece was found in the Washington Free Beacon on May 22: “Miss Uncongenality,” by Matthew Continetti.

The headline tells you that mud is about to be tossed. “Congeniality” is the award the loser in the beauty contests receives, and Continetti is unwilling to tell his readers that Republican winners and losers in presidential campaigns often lacked the quality: Coolidge was taciturn, Ike was aloof, Nixon was resentful, and Dole was dour. Good candidates or presidents? Yes and no, but what has congeniality to do with it?

After the headline, most charges against Clinton are unsupported by facts. At a recent press conference, Continetti suggests, Clinton wanted to ward off questions by “raising her hand empress-like.” And how does an empress raise her hand in a manner different from commoners? Readers don’t know, but it sure sounds bad.

As does every comment about Clinton, without explaining the badness:

“Voting for the Iraq war was a ‘mistake,’ like the one you make on a test.” How does he know her ‘mistake’ (supporting the war in Iraq) was made the same way you make a mistake on a grammar quiz or misidentify a figure in European history? Was her mistake possibly made based on false or incomplete information or on misreading the political and cultural forces in the Middle East?

She released a “blizzard of Clintonian misdirection, omission, dodging, bogus sentimentality, false confidence, and aw-shucks populism.” It’s hard to swallow Continetti’s mind-reading verbiage. Perhaps she was confident (say about her role in the Benghazi attack). What’s “aw-shucks” about her or anyone else’s populism in our current age of greed?

Readers will not be surprised to find the article riddled with “may” and “might” phrases, suggesting the author wants them to assume: “may not work,” or “may begin to change” or “may be the wrong choice.”

Tealeaves reading is no substitute for information and insight-filled journalism.

In the next 17 months before the 2016 election, readers can expect a blizzard of articles such as the ones in the New Republic and the Washington Free Beacon. Long and fact-filled pieces in the New York Times and in other media could provide an antidote.