Sixty-one years ago, Percy Green began a hunger strike in front of the office of then-St. Louis Treasurer John H. “Jack” Dwyer to demand the city remove tax money from Jefferson Bank, which had no Black employees. Green, who had already been branded a “habitual troublemaker” by the St. Louis Globe-Democrat and secretly targeted for dirty tricks by J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO, was arrested within three hours on trespass charges. It was the first of 100 arrests over 20 years. A year later, in 1964, he and a friend climbed the unfinished Gateway Arch to dramatize the demands to hire Black people on that project and in downtown St. Louis, where almost none was employed. After the protest, he was fired by McDonnell Douglas and challenged his dismissal all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in a case that established new job discrimination protections. Green, leading the ACTION civil rights group helped unmask the Veiled Prophet in all his Confederate regalia, persuaded the telephone company to hire Black phone installers and faced turmoil in his marriage because Hoover’s COINTELPRO program systematically discredited civil rights leaders from the Rev. Martin Luther Jr. on down. Green headed an affirmative action program in City Hall until Mayor Francis Slay sidelined him and went on to be active in the American Civil Liberties Union of Eastern Missouri. Last summer, Green reflected in an interview with GJR publisher William H. Freivogel on his long career as a civil rights leader.

Freivogel: Good morning, Percy. How and to what extent do you think Ferguson and its aftermath have changed things and what things have slid backwards? What things never did get changed? To what extent did Ferguson have a lasting result?

Green: Well, … how did Ferguson become Ferguson?…Well, Ferguson got to be Ferguson because, as I see it, most of the little small municipalities learn their cues or they learn their way from larger cities. And with St. Louis being the dominant city in the area, historically… St. Louis was being run by the white power structure and the white power structure, as I see it, are your large businesses in the area. They’re the ones that control the politics; they set the standards. And, of course, smaller cities, when they come into being, they mimic what they’ve seen. They join some of the associations like the Veiled Prophet and some of these other clubs where chief executive officers of other businesses are members.

They pass that information on to smaller cities and municipalities. And so, that’s a learning experience for them when they come into being. And so, Ferguson mimics what St. Louis does. Ferguson has become known pretty much as a result of the murder of Mike Brown. Now, the thing about St. Louis is that it’s been a killing police department, it’s been murdering a young Black male, or Black males, historically, under the auspices of so-called fleeing suspects. And they use this thing that almost all police departments utilize, and that is that qualified immunity. And so, that is a standard throughout, where… Police can kill, then claim as if the person that they killed pointed something at them, looked like it was a weapon, and out of self-defense, they had to fire their gun, and ended up killing the person.

Now, the person is dead. They can’t dispute that. The only way you can dispute that is if there was someone that was observing it, and they’re willing to come forward. Most of the time, that is not the case, because many folks, if they see a policeman murdering, they fear that if they tell the truth on the police, that there are consequences… And so, as a result, they’ll claim as if they didn’t see anything.

Video cameras make a difference

Green: The only thing that is going now for the poor, and that’s poor Blacks and whites, is this video camera thing. The mere fact now folks can videotape situations and circumstances pertaining to a policeman’s involvement.

At least they can show pretty much what occurred. And even then, you find conflicts where the police report conflicts with the video that is taken of the event, which goes to show you that in absence of the video, how a policeman has been lying consistently, for all practical purposes, in terms of their report, to justify their actions when in fact, many times, or even most of the time, there is no justification for such. So, I’m just saying that Ferguson got to be a judge.

Just only learned from the city of St. Louis over a period of time. They had the same program in goal that was in place from its inception. So as I see it, the same will hold true for all of the other little municipalities.

I’m just saying that Ferguson only learned from the city of St. Louis over the period of time from its inception. The only thing with Ferguson is there was an enormous number who witnessed it Black and white. That pretty much made it newsworthy. Because many times, if it’s only Blacks that witness a particular crime, it is minimized in terms of value or whether or not it is even considered as news. But if there happened to be some whites who happened to step forward and saw the questionable situation, then of course, in some cases, some fair-minded news directors might qualify it as newsworthy. And then as a result, that then became the trigger for it being exposed to the wider community.

Freivogel: Do you think what you describe as the way police get away with killing Blacks on the street is that still true today? Or has the video and changes after Ferguson made a difference?

Green: It still holds true today. Video has caused some change in some communities to the extent that the video is not destroyed in some manner. In many cases, if by chance, you know, if by chance, the video exists, there are two tracks of videos that I would like to address. One is the police department; many times you see they turn their video off. In some cases, they…can’t turn it off. And as a result, John Q. Public gets the benefit of some, of some truth.

But if by chance, there is any way, form or fashion that the police department can claim that, well, we don’t know what the person did before the video was turned on — consequently, there’s reason to believe that the suspect did this, that, and the other, prior to the video coming on. And so as a result, we have reason to believe the policeman was justified in doing the shooting… So, wherever there’s a possibility for the police department to lie to protect their interests, they will do so. Even with the video revealing the incident to the contrary of their report.

I will admit, thank goodness that at least we have the video, the telephone videos now where John Q. Public happened to be… somewhere close to the incident, that they could videotape it. And that has done two things. It reveals how you cannot accept the policeman’s word alone. And then of course it gave rise to some fairness to the public.

Climbing the Arch for jobs

Freivogel: Tell me about climbing the Arch. Was that 1964? If you were telling me the story of your civil rights activism, does it start before your climb up the Arch?

Green: Oh, yes. My involvement in the protest movement occurred prior to the Arch. It started when I first became involved in CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) in 1962. I believe it was, by a friend of mine named Joe Fischetti. He and I worked at McDonnell Douglas, and he wanted me to attend a CORE meeting… After he approached me about attending his meeting about four or five times, finally, I went to one, and I found it to be very interesting. At the meeting, it appeared to be educators, Black and whites, were at the meeting, and they were discussing employment.

They were discussing employment discrimination at stores like Famous Barr and Stix. And discussing how they were going to try to get the company or encourage these companies to hire some Blacks in places where Blacks never had been hired. And one of the persons at the meeting that was really impressive to me was Eugene Tournour. He was a Washington University student at the time, and he seemed to be very, very knowledgeable. At the meetings were Charlie Oldham, Marian Oldham, and others.

Freivogel: These 1962 CORE meetings, were before the Jefferson Bank sit-in?

Green: Oh, yes. Jefferson Bank didn’t occur until 1963. Yeah, in 1962, at the time I came on board, shortly afterwards we had what was called a boycott of Kroger. We were trying to get Blacks into some of the jobs at Kroger grocery stores. Kroger had about five stores in what was considered the Black community, but they had no Black cashiers, no Blacks working in the store, period. And so CORE was asking for some butchers and some cashiers. And eventually we got some…

(At Jefferson Bank) they were asking for tellers. We learned that East St. Louis had an action against the banks there and it was successful after a few weeks and it made big news… One of the persons at the Core meeting said, “Well what about Jefferson Bank?” Well, many of us weren’t even aware of any problem at Jefferson Bank. But someone reported that Jefferson Bank had moved to a commercial location from Jefferson and Franklin (in the Black community.)

The change was huge. People’s lives were ruined because Jefferson Bank was so valuable to them. It was a white owned bank but it served the Black community. It moved to Jefferson and Washington, which was predominantly white. Why would CORE not make a demand on Jefferson Bank for a teller job since Jefferson Bank had been in the Black community for over 20-some odd years, and they didn’t have any Blacks in any responsible position, and so that’s the way that, so that’s how that pretty much got started. The demand was made,

Freivogel: So, did you meet Bill Clay at that time, or did you already know Bill Clay?

Green: No, I did not meet Bill Clay until Jefferson Bank. Bill Clay never came; he wasn’t coming to the meetings at the time, although many of the people who were coming to the meetings knew Bill Clay because from what I later learned is that many of the people who were CORE members at the time, they were also had recently helped Bill Clay to become the leader of the 26th Ward. And so these were pretty much the same people; the old hands and whatnot. It was an interracial group that at the time, they worked diligently — from what I understand — to turn out to vote, which got Bill Clay elected.

Jordan Chambers, who was looked upon as the Black mayor of St. Louis during that time, felt Bill Clay running in the 26th Ward without his blessing was not looked upon favorably by him or that, you know, in his organization. But Bill Clay, he won, and there was a strained relationship between the two of them.

Freivogel: Did you ever get arrested at the Jefferson Bank sit-ins?

Green: Yeah… Not at the big sit-in but later during a solo arrest at the city hall at the treasurer’s office… Jack Dwyer was the city treasurer and CORE had asked the city to take his money out of Jefferson Bank because the bank was discriminating. And so I was arrested for trespass. I took vacation at my job off because I knew I was going to be arrested and I didn’t want no linkage between me being arrested and my working at McDonnell Douglas. So I took vacation time and I was arrested and bonded out,

Up the Arch

I had become the chairman of the Employment Committee, and we had started our research into the Gateway Arch activities as to what their employment picture was like. And, and of course, during this period, CORE was — we were having a debate as to whether the group was going to continue to use civil disobedience, or whether we were going to cease and desist from using civil disobedience whether the group was going to transition to using Saul Alinsky’s approach in Chicago, whether that was called community action. We didn’t think that community action would work here in the City of St. Louis because it was too intransigent. We eventually set up ACTION.

After we have done this research on the Arch, we needed to go ahead and for the sake of trying to get some jobs at the Arch. Richard Daley was part of the group that eventually became ACTION. Daley and I both were arrested on July the 14th of 1964. Daley was an engineering student.

We were arrested when we came down because I had to go to work. See, I was working at McDonnell Douglas at the time from 12 o’clock to 7 in the morning. We climbed the Arch about 12 o’clock during lunchtime because that’s when the workers were in a relaxed mode. We climbed a certain level where we would, you know, not be close enough to the workers. We were conscious enough not to get close enough to the workers that could possibly cause an accident and for us to be blamed.

So, the Arch at the time was at the 300 foot mark. We climbed 125 feet up. We knew we were at about 125 feet because they had the markings, you know? And so we climbed up and we remained there until about 5:30 or 6 o’clock. We had to come down because we had already calculated that upon us coming down, we’d be arrested and we’d be busy making it out to the police. So we would bond out, so I could refresh and be at work. So I wouldn’t have any black marks on my work record and give them a reason to terminate me for some strange reason. So that was the thinking. Otherwise, we would have remained there much longer.

Freivogel: Did you make it to work that night?

Green: Yeah… We were arrested and Daley, unbeknownst to me, ended up going to the Workhouse. I wasn’t even aware of that. But me, personally, I was bailed out. And I thought, sure, that Daley was bound out, too. But I later learned by talking to him that he never was bailed out. So he remained in jail and ended up with a few days or so in the Workhouse.

Freivogel: Were you ever convicted for going up the Arch?

Green: No. Nicholas Katzenbach (Kennedy’s assistant attorney general) you know, Washington, D.C., intervened. They had all of the charges dropped against Daley and I. General peace disturbance and individual peace disturbance were the charges, I think it was. And they were dropped.

Freivogel: Were those, so those were state charges?

Green: So those were the first arrests. That was the second time I was arrested in civil rights, you know, after the Jack Dwyer Jefferson Bank protest. … I was arrested many times after that.

Freivogel: How many times have you been arrested?

Green: Over a hundred times. In a 20-year period, over a hundred and some odd times. I have been arrested three and four times a year for about 20 years. Not just alone now, that’d be in conjunction with other folks being arrested.

Freivogel: So what had you researched about jobs that were available on who was building the Gateway Arch?

Green: There were no Blacks involved. Yeah, no Black employees. And at the same time, there were no Black contractors. And so now for this, the general contractor was named MacDonald. And after, when we went in to negotiate for the job, or we were doing the research, when we went to the office of MacDonald, at the Arch. He looked at us and said why don’t you find us some workers. We told them that was his job. Blacks were being drafted into the military and were doing all sorts of construction engineering, which is road construction, doing a lot of construction type work. How is it that he can’t find any Blacks to do construction work?

So he just insists that he put forth the effort, but he just couldn’t find any qualified people. And that was the end of it. And so we told him that eventually, after a couple of weeks, that that wasn’t sufficient. And that we’re giving him and the whole entire construction industry 10 days to hire a thousand Blacks in all job classification. And of course, we knew that we were going to carry on the action. So, we know that he, or the construction industry, were not going to do any more in 10 days than they would have done in 10 years, because that was our position. So, after about 10 days and whatnot, we had already laid out the strategy as to how we were going to do the Arch project.

We couldn’t afford to let the press know ahead of time about climbing the Arch because they would have informed the police department and we never would have gotten close enough to it to even do it.

So, we had to set up a diversionary, surreptitious scheme. We called and told the press that we’re having a big, major picket line there at the National Park Service where the tourists come in. We told them that we were going to have a direct action protest there, just to get the press to come there. And then of course, if we were successful in climbing the Arch, once the press was there, then we were going to inform them that there were two demonstrators who had climbed the Arch and that in fact is what occurred. And that’s how we were able to get the press there to do some of the covering.

Green v. McDonnell Douglas

Freivogel: Did McDonnell Douglas fire you for climbing the Arch?

Green: Yeah, 30 days afterwards… They claimed they were having a reduction in workforce. And at this time, I had transitioned from my union job to a research and development job. And they saw fit, even though I was the only Black in this particular category, they saw fit about 30 days afterwards on my birthday.

They argued that they were getting rid of 10 other people also, who happened to be white. But at the time, MacDonald had about 600 research and development technicians. I was the only one. And they claimed that they were laying off 10 folks in a reduction in workforce. And I happened to be one of the unlucky ones, along with nine or 10 other whites. My argument was that they didn’t have a sufficient number of Blacks in the first place to be laying off any Blacks. I mean, the fact that they didn’t have any. Even if they had 10 Blacks, 600 whites, and they were having a layoff, they were having an insufficient number of Black workers in the category.

And then, of course, when the 1964 Civil Rights Act went into effect, a year later, they were still hiring in a job classification that I had held. So I went back in 1965, when the 1964 Civil Rights Act employment section went into effect, and reapplied for the job that I had held for seven years. They had advertised for that job all along, all during that period. And they refused to hire me back in that job classification. And that was the grounds that I filed my complaint on, which went to the Supreme Court of Green versus McDonald. Lou Gilden ended up being my attorney.

Freivogel: And that was an important decision that laid out the test for employment discrimination.

Green: Exactly. The St. Louis NAACP gave me a legendary award.

Freivogel: At the time of the Arch you were having conversations with Union Electric and Laclede Gas to hire more Blacks?

Green: That McDonald construction guy said, you know, ‘we can’t find qualified people.’ They didn’t want to send a Black worker into a house where a white housewife might be home. That was with the utility companies here. That was 1964 or ‘65. That was the utility companies. Southwestern Bell, Laclede Gas and Union Electric. That was where the chief executive officers then pointed out the reason why they didn’t hire any Black telephone installer, because it would create too much of a problem of Blacks going into white homes, is the way they put it.

We were advocating more and better paying jobs for Black men. Because we felt that if Black men in the community were allowed to have decent paying jobs, that would cut down on the possibility of unlawful activities in order to satisfy family needs and desires and whatnot. And these were jobs that didn’t require a degree. You didn’t have to have a degree to install a phone. You could learn on-the-job training. And we felt you learned that job, just like in the military.

In the military they taught folks how to fire weapons that they’d never seen before and become proficient at doing it. And so, we went after those particular jobs while the NAACP was primarily advocating for professional jobs. We felt that it would be more productive in the community if Black males could get some of these good-paying jobs that didn’t require an education and be able to provide for one’s family. And of course, because those are the jobs that could make a bigger difference or whatnot, that was the position that they took then. So we went after them.

They eventually did begin to start hiring, but when they took a Black out of doing utility work and making the first Black telephone installer, all of the white workers went on a wildcat strike for two or three days. During that struggle I was arrested a couple of times. I was at Southwestern Bell blocking the traffic, locking the employees in. And during some disruption of the business, we locked the doors. We locked out employees. And a couple of times, we took some dog poop at Laclede Gas and painted the windows… We were tired of Laclede Gas dog poop.

We were arrested for that, but civil disobedience has been our thing, and we were… we had been very colorful with our demonstrations. One company opened a building on Tucker and some of our action members were arrested because we went in there with some with some syrup and poured it all over their their new carpet letting them know that ACTION was still sticking in there, we’re sticking with our protest demonstration against them,

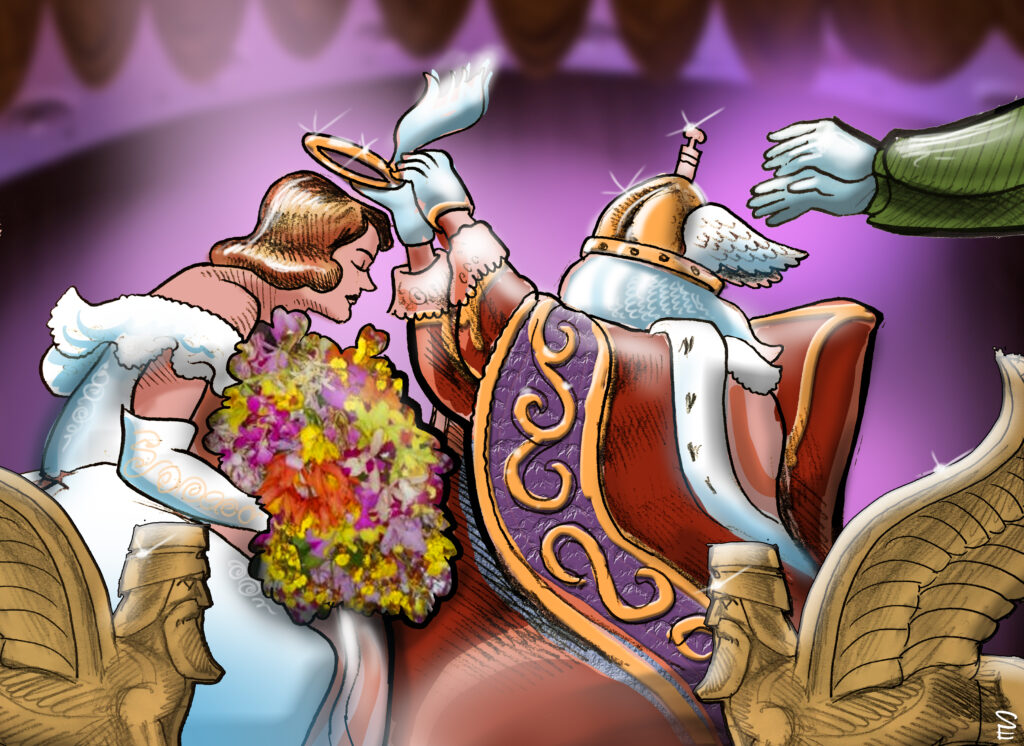

Unmasking the VP

From the utility companies, that’s how we gravitated into the VP. We learned that some of the daughters’ names were listed in the newspaper as related to chief executive officers of the companies that were running Southwestern Bell and Laclede Gas. No wonder these companies are afraid to do the right thing because socially they are in the same racist environment where you almost give a pledge to say “I will maintain this type of social and class thing.”

No wonder none of these chief executive officers want to say that they will do the right thing and start hiring Blacks for fear of what the other members in this social group could very well brand them, or how they could be disciplined within that particular group for doing something that is not considered as accepted behavior. In other words, it would be unwritten code, and even if some of the chief executive officers wanted to do the right thing, they are pretty much prevented from doing so if they want to be in good standing in this particular organization.

That was the way that we kind of rationalized some of them not wanting to break out of that mold and start doing the right thing. That’s how we pointed out how the white power structure functioned. To educate the community, we then did some research to see how this organization got to be what it became, and that took us back to the 1870s, 1878, the day of the General Strike whereby the workers both Black and white showed their strength.

There was this general who was a Slayback, a business person who was supposedly a Confederate, and they then created the VP. There was an element of the organization that eventually intimidated the workers and forced them back to the work and then of course a celebration of breaking the strike.

(Editor’s note: The Slayback mentioned by Green was Confederate Col. Alonzo William Slayback. An interesting 2007 article in St. Louis Magazine by Ellen F. Harris reports that Slayback Slayback was a Confederate cavalry officer who commanded the Slayback Lancers during the Civil War. After the war he set up a law office in St. Louis where his brother, Charles, was a grain merchant. The two former Confederates thought the Union had ruined St. Louis and would benefit from some Mardi Gras style festivities. Alonzo Slayback was particularly annoyed by the new newspaper in town, Joseph Pulitzer’s Post-Dispatch and its first editor, John Cockerill. In 1882 Slayback barged into a meeting Cockerill was holding at the paper. Cockerill, thinking Slayback was armed, shot him dead.)

Some of the research we did reveals that they (the Slaybacks) were the ones that came up with the hood and robes that look like the Ku Klux Klan. But then later, I learned that this image appeared with the VP before the Ku Klux Klan, suggesting that the Ku Klux Klan got its idea from the VP image rather than the opposite.

We felt the Veiled Prophet was guilty of sexism, as well as elitism. They were auctioning off their daughters among that same class? You know, I mean, that was why we would refer to it as being sexist. We felt as if that the VP should be abolished altogether in terms of the city of St. Louis. However, if it is going to exist at all, have it out there in Ladue. We felt the city of St. Louis is to become a city for all and be prosperous. And to eradicate and start moving away from it, from this racist image and sexist image, etc. It needs to be abolished altogether.

Freivogel: How many years did you march at the Veiled Prophet Ball?

Green: We marched from 1965 up until 1972. We did the unveiling in 1972. I believe it was December 1972. We still carried on a protest. We wanted a lawsuit where they could no longer hold the VP at the Kiel Auditorium. Ray Howard was an attorney then, and they had to move from the Kiel Auditorium, and they located at the Chase Park Plaza. Then we carried on some demonstrations there at the Chase Park Plaza. The unveiling occurred, though, at Kiel.

Freivogel: Who was the young woman who came down the rope?

Green: Gena Scott. But it was a two-person team, two females, Jane Sauer and Gena Scott. Jane Sauer was the one that distributed the leaflets as a diversionary. And then Gena came down the, I forget what you call those poles, the stage cable. And then, of course, one of the cables pulled loose from the ceiling. She fell about six feet, knocking the wind out of her and bruised her ribs. But then she got up, went behind the curtain, came up behind the VP. That was Tom K. Smith of Monsanto. She snatched the mask off and threw it out there on the floor. And that blew the minds of all of those that were present at that point, you know.

(Editor’s note: The Post-Dispatch and other media did not publish the identity of the Veiled Prophet.)

It was just that it was our philosophy that we were a non-violent organization…. I mean, that was the only guidance that we had. I didn’t want to encourage nobody to engage in something that was going to be felonious and they’re going to end up spending a whole lot of time in a penitentiary. So,the events that we executed amounted to a misdemeanor. We wanted to disrupt things of that nature and I felt then the news media didn’t have any problem covering disruption.

You know what they (journalists) would do if they knew about it ahead of time, they would show their support to the establishment by informing the police. But they couldn’t inform the police about something, if they didn’t know anything about it. The news media didn’t have no problem covering the arrest situation of Black people or people that are being arrested on behalf of Black folks, because it was about being arrested. It was about that law and order thing. So we were playing on that. I would develop demonstrations that would give the news media what I know that they would like to respond to, but at the same time, it would serve our interests in exposing what I want to be exposed, even though it would be done at a minimum, but at least it would be exposed to some degree.

Freivogel: Tell me about your years as the mayor’s contract compliance officer.

Green: Freeman Bosley was the mayor at the time. And I was the director of contract compliance and certification. And that job was to see that minority contractors would get at least 25% of the amount of the contract that is let. And women-owned businesses would get 5% — that’s why they call it the 25/5.

Freivogel: What was it like to work from the inside?

Green: Oh, it was okay as long as I had the authority to make decisions. (Mayor Francis) Slay, I ended up being fired. My whole entire department was terminated. And some of it was moved to the airport because Slay wanted me to certify some front companies to get some contracts. And I wouldn’t do it. And so as a result, he tried to get rid of my department and did so. I was terminated and all of my staff was eventually terminated. When I was there, I tried to make sure that legitimate Black-owned businesses and women-owned businesses got city contracts so they could build, as opposed to front companies.

You had a whole bunch of some of the businesses, white-owned businesses. They would create a side order or grits and claim it was a minority-owned business when, in fact, they were not. You know, they were just a front company. And I would have to do an investigation on all of these companies to determine who is certifiable and who should not be. And then if a certifiable company later became a front company to decertify it. And we took pride in our operation because I wouldn’t accept anything to the contrary. So as a result, Slay saw fit to get rid of me and he couldn’t corrupt my staff so he got rid of them too.

Freivogel: When did you start getting associated with the ACLU?

Green: It seemed like those guys wanted to do the right thing. I will work with them and that’s how I agreed to be a board member. Because it was all about working with them. And then, of course, one of them said that the ACLU had not ever had a Black executive director. And they wanted to know whether or not I would help in trying to find such. And I think that was the hook that really caught me. I said, well, “Okay, I’ll do what I can to help you out with that task.”

Brenda (Jones) stood out because Brenda had done her homework so well, in terms of knowing something about the history of the ACLU. She did such a superb job doing an interview.

And Joe Fasetti was a poet, white male. He used to read poetry at Gaslight Square. When I was working at McDonnell Douglas, in the department, he was there and he and I became very good friends because we kind of worked side by side…building wire harnesses. And. So, by virtue of us working together, communicating together, sometimes having lunch together and everything. He and I became associates. And that’s when. He started saying, “Hey, I want to know, what’s the chances of you going to these meetings with me?” And that’s what he was telling me about the core.

And I said, “Well, what is this? What are these meetings about?” So he was explaining to me that it was about trying to break up racial discrimination. And he said, “Hey, you ought to come and check it out.” And so after a couple of times, I accepted the invitation. And then we were going to these meetings together. And then, of course, during these meetings, that’s how I started observing some of these other people, like Eugene Tournour.

Freivogel: Tell me more about him.

Green: Oh, Eugene Tournour was fantastic. Eugene was a student and he was going out with his wife, then girlfriend, named Roberta Tournour. And they were both students at the time… Now, at the time, I kept hearing this term, “white power structure.” Some of the Blacks there who had been members, I heard them using the term, and I heard whites using the term. They were just using it, and I’m just new, so I wanted to know, well, what in the hell is the white power structure?

So, after I’ve observed Eugene Tournour who seemed to have so much knowledge in being responsive to so much other activity that was going on at these meetings, I finally began to ask him. I said, “Listen, I heard you all using this term. What is the white power structure?” And he explained to me that the white power structure was the invisible government. It was the chief executive officers of all of these major companies in all municipalities, and most of the residents, most of the people are unaware of their decision-making and how they govern their life or whatnot. And I said, “Well, that makes sense.” He said, most of the people are not even aware of these particular people. They’re not familiar with their names or their functions, and everything.

So, I mean, that was one classic thing. The other is that I was so naive when I was telling him, I said, ‘Well, look, at the time of doing the Jefferson Bank.’ I told him, ‘Well, look, I’m going to take vacation time, and I’m going to engage in some civil disobedience to keep the protests alive at Jefferson Bank.’ He said to me, “Well, now, be careful now, because you have your job, your livelihood and you don’t want to do anything that is going to allow them to terminate you.” I say, “Well, I’m not going to do anything that will give him reason to terminate me because I come to work every day. I come on time, and I perform while I’m there. So, I’m not going to give him any reason to terminate me.”

He said, “But that ain’t enough.” I said, “What do you mean, Gene?” He said, “Businesses, they can terminate you and will. They can terminate you regardless of whether you’re a top performer or whatever else. And they can get away with it.” I said, “Well, I’m not going to… I just can’t believe that”’

And it wasn’t until I met my Waterloo there at the arch, after climbing it, that I had just received a performance of excellence in terms of my performance on the job. I hadn’t been absent or tardy, but yet they saw fit to lay me off or whatnot.

I said, “Damn.” And then later, I learned from a contract that management has the right, in this union contract, to manage and/or mismanage. That blew me away. I mean, but that reminded me about what Gene had informed me. And, I was just so naive at the time. I mean, I felt as if it was okay, as long as I do what I want to do on my own time, I’m not giving anything up and I’m not linking my outside activities with where I work in any negative manner, because when, when I was arrested, I just told them that I was, that I was unemployed, or I told them that I don’t give that information out of something to that effect.

But yet, I was terminated. So I give credit to Gene Tournoura in providing me the basics of the white power structure. First of all, identifying it and how it controls all communities by way of contributions to the politicians. The institutions in the area, how they control it, because all of them need money. And, all of the businesses, the big businesses, got bigger. If they have the biggest budgets, they’re the one that can make the contribution, and their contributions are always influential.

Freivogel: So, would you say, Percy, that the white power structure still controls St. Louis?

Green: Yes.

Freivogel: Even with the Black mayor?

Green: Even with the Black mayor…The state politicians and whatnot are overwhelmingly white and, of course, they’re certainly tied to statewide businesses. That’s why they get most of their funding, like from Anheuser-Busch and the utility companies. If you look at the politicians and where they receive their money, it comes from various sources of people that have money. And then, of course, the people who have money, they have interests and they like to have their interests taken care of and their interests are served by the politicians because the politicians want to continue to receive that money, those revenues, in order to stay in power. And then, of course, the folks with money, if they can’t buy this particular politician, they’ll buy another one. But we know that money rules politics and whatnot.

Freivogel: Where did you grow up in St. Louis?

Green: I’m a graduate of Vashon. As a matter of fact, they just inducted me into the Hall of Fame a couple of years ago. That wasn’t newsworthy. They sent news out on that and nobody said what happened. You know, if I said I was going to be arrested, the news would have been there big time or whatnot.

Freivogel: How old are you and were you ever investigated by Hoover COINTELPRO?

Green: I’m 88. And, as a matter of fact, COINTELPRO is responsible for breaking up my marriage to my son’s mother. They not only sent out poison pen letters, but they called Betty in the wee hours of the morning to come down and claim my body. But the big thing that got to her is she wanted to get out of the movement altogether. And we separated because I wasn’t going to let it drive me out of the movement. But then I had to be mindful of her safety and our kid. So, we parted company and whatnot for the sake of safety. So, if something was going to happen, target me. I wanted to be the one that they take down and not my wife and kid.

(Editor’s Note: Percy Green will turn 90 in August.)