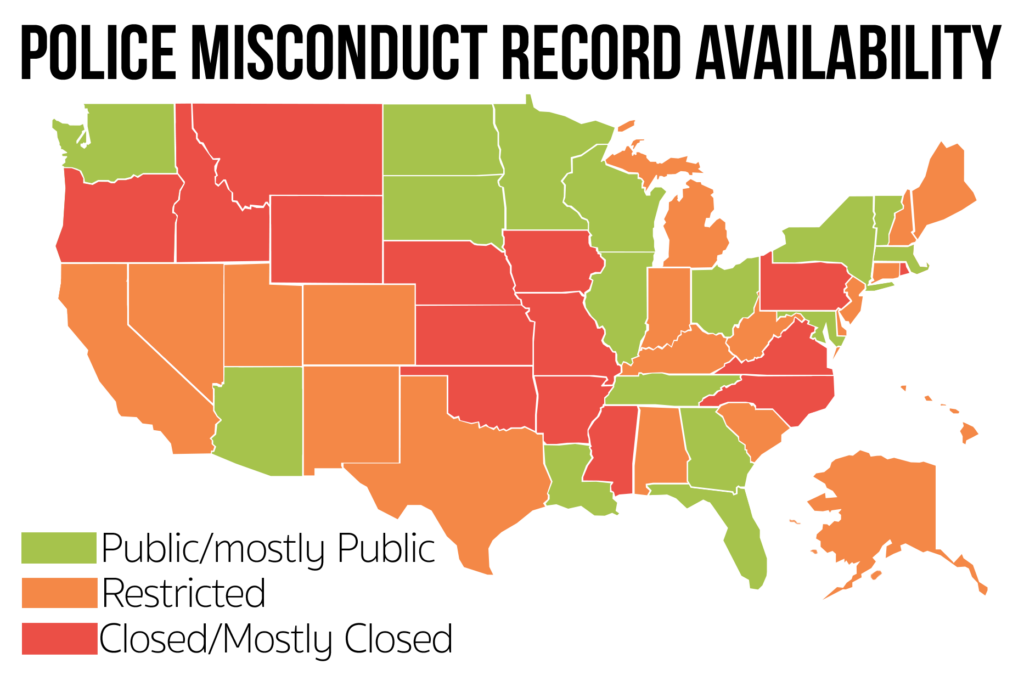

Police misconduct records are either secret or difficult to access in a majority of states – 35 of them plus Washington, D.C. But the breeze of openness is blowing. Seven big states have opened records in recent years – California, New York, Illinois, Colorado, Massachusetts, Oregon and Maryland.

Now 15 states have laws that allow these records to be mostly available to the public – up from 12 a few years ago.

Legal experts say transparency of police misconduct records is one of the keys to police reform. David Harris, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh, put it this way: “One thing that has changed is greater transparency. We have seen a number of jurisdictions enhancing and changing the way police misconduct records have been handled. You can’t have real accountability with the public unless you are willing to share information.”

The modest uptick in openness is the result of a combination of court decisions and reform laws passed since the murder of George Floyd. New York, Massachusetts, Colorado, Oregon and Maryland enacted laws in the past year opening records that were previously closed. California passed a law opening some records in 2018.

In Illinois, the Invisible Institute won a court decision in 2014, Kalven v. City of Chicago, granting public access to misconduct records by striking down exemptions law enforcement agencies had claimed when denying public record requests.

New York state repealed section 50-a of the state’s civil rights law last year and this year made more than 300,000 police misconduct records public. Indiana passed a bi-partisan police reform bill last month that publishes the names of officers decertified for misconduct.

However, there are still barriers to accountability, even in some of the states that have begun to open up.

In Illinois, a widely touted police reform law passed this year included a provision that closed the state Professional Conduct Database of officers who resigned, were fired or were suspended for violating department policy. Not only are the names withheld but also the supporting documents. To get statewide records, a person would have to contact each of the almost 900 police departments and request these misconduct records individually.

In Pennsylvania, Gov. Tom Wolf signed a bill into law in 2020 that created a database to track police misconduct statewide and force agencies to check the database before hiring an officer. But the legislature closed the database to the public.

Indiana’s bipartisan law passed this spring required an Internet listing of the names of all officers disciplined, but closes the much more plentiful investigations that don’t end in punishment. Colorado opened records but its law was not retroactive and required requesters to have specific information about the misconduct. Oregon created a database of officers disciplined but did not open records of investigations that didn’t lead to discipline.

In New York, after the repeal of 50-a, the public records group MuckRock filed a public record request for police misconduct records from the Town of Manlius Police Department in New York and was told to pay $47,504 to see them.

Beryl Lipton, projects editor at MuckRock says “in New York the police unions have done solid work of trying combat the release of materials, with many agencies refusing to release records while those court battles played out; still others have claimed that the law does not apply retroactively to existing records, and the courts have landed on either side of that point.”

Last month, state Supreme Court Justice Ann Marie Taddeo issued an order agreeing with the Brighton Police Patrolman Association that the repeal of 50a was not retroactive. The order would close all misconduct records before the summer of 2020. Two other Supreme Court justices in other parts of the state have ruled it is retroactive, so a decision of the state Court of Appeals may be required.

Nationwide, the majority of law enforcement agencies still close records or make them hard to obtain. They claim they are personnel matters, privacy violations, or ongoing investigations that could be compromised. They are backed by strong law enforcement unions and the law enforcement bills of rights that protect the privacy rights of officers over the public’s right to know.

The National Decertification Index published by the International Association of Directors of Law Enforcement Standards and Training compiles 30,257 decertifications from 45 state agencies, but the names are closed to the public.

Sam Stecklow, a journalist with the Invisible Institute, a nonprofit journalistic group focused on public accountability, said in an interview some of the states where it has become easier to request records are Illinois, New York Florida, Utah, New York and some cities in Texas. He said Nebraska, Hawaii, Kansas and Virginia are closed to the public.

“There are some states that we haven’t even been able to work at all in because they … require you to be a resident to make a request,” Stecklow said. “So we just haven’t really tried there. That includes Tennessee and Delaware and Virginia as well.”

Stecklow said many more states release the names of officers only in the rare instances where complaints are sustained rather than the much more frequent instances where the department decides not to punish the officer.

“I think it’s important to make a distinction regarding sustained vs. not sustained cases,” he said. “Many states will allow the release of records about a case in which discipline is imposed, but that is a very small minority of police misconduct investigations.”

Stecklow said if state legislatures wanted to settle the question of requesting misconduct records, they could easily do so.

“They could very easily amend FOIA and explicitly say you know a record that either contains an allegation of police misconduct, or an investigation into an allegation of police misconduct or a disciplinary record regarding misconduct is always public,” Stecklow said.

Related Content: This story was funded through a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and distributed by the Associated Press in May 2021

Kallie Cox is the editor-in-chief of The Daily Egyptian, the student newspaper of Southern Illinois University Carbondale and can be reached at Kcox@dailyegyptian.com or on Twitter @KallieECox. William H. Freivogel is a professor at Southern Illinois University and member of the Missouri Bar. Zora Raglow-DeFranco, a law student at Case Western, contributed to this report. This story is part of a project on police accountability funded by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.