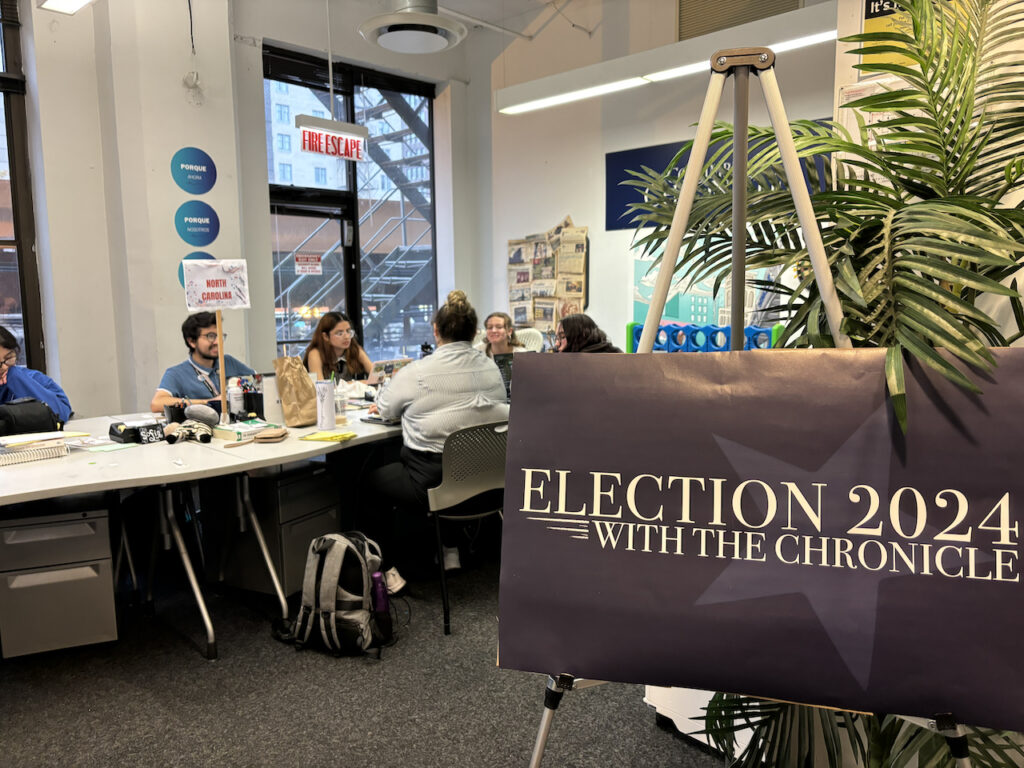

The day before the Nov. 5 election, I carried a bundle of poles into the newsroom of the Columbia Chronicle in an attempt to recreate one of my core memories from The Washington Post, where I was a staff writer for 14 years.

I made signs for the seven swing states we’d be watching on election night, and I placed them on the poles around the newsroom where the reporters could cluster as they watched the returns come in. We also rallied our alum and journalism allies to contribute to a gift fund so we could buy pizza, another election night tradition.

For many journalists, election night is sacred. Like voting, it’s a participatory part of the democratic system. After months of reporting, of digging into the platforms of candidates, of trying to understand the voting choices people will make, after watching the numbers and anticipating how close a race will be, election night brings it all together. We get to see the winners we have to hold accountable after they are elected and take office. We do that on behalf of a public that is increasingly reluctant to allow us that protected duty.

As the faculty advisor to a diverse newsroom of Generation Z journalists, I spend a lot of time thinking through and sometimes reconsidering the rules and conventions I was taught to embrace as a young reporter in a white, patriarchal industry.

Some of the standards are non-negotiable. To earn trust, journalists have always and will always need to protect their credibility. Our coverage is driven by facts. We separate news and editorial and resist sharing our personal opinions in a public forum. Our duty is to our readers and not our owner, which, in the case of a financially dependent student newspaper, is Columbia College.

But we spend a lot of time talking about our paper as an institution and why we do the things we do. I do this because my students and their peers are deeply committed to inclusion and equity, and that was not a core value taught to most journalists my age. Our notion of fairness was to “get both sides,” a false equivalency I now warn my student reporters not to do. I was decades into my career before I learned to embrace Maynard’s Fault Lines and purposefully seek people who didn’t share my experience and to include them in my reporting. I have come to realize that the system that produced me as a journalist was an oppressive one. I don’t have to teach or enforce the parts of it that need to change.

In many ways, The Washington Post newsroom I grew up in was filled with privilege. It was majority white. People were highly educated. I was an outlier because I had gone to state schools and not the Ivy League. I also had grown up solidly working class. But even for those of who didn’t come from money, working at The Washington Post meant you could earn a decent living. And no matter who got elected, you were most likely to be part of a protected class. You’d end up okay. It was easy to focus on the rest of the nation.

That’s not the case in the student newsroom where I now advise and teach. We have students from nearly every marginalized group in America. We have trans students and students whose parents are undocumented. We have students who were unhoused at some point, students who have limited access to health care and students who are Muslim. Nearly a third of the staff is Hispanic. Many are working two jobs to pay for school at a college that has a majority queer and BIPOC student body but majority white faculty.

They have opinions and dreams, and even though they work hard to be objective in their reporting, election night is not objective. Impartiality is a powerful luxury.

As they came back to the newsroom in the rain after reporting, I watched their faces as they took in the election map and saw how well Republican candidate and former President Donald Trump was doing. Putting aside their journalism credentials, many of them see him as a threat, which is understandable. They watched and reported what he said on the campaign trail. They took him at his word that if elected, he would do all of the things he promised:

- Undertake the largest mass deportation of undocumented people in U.S. history

- Cut climate regulations

- Use the new immunity granted by the U.S. Supreme Court to go after his political opponents

- Be a “dictator” on his first day in office

- Help end the brutal war in Gaza on Israel’s terms

In the early hours of Nov. 6, when it became clear that Trump had won, I did two things: First, I helped the campus news editor get the story out, and then, along with our bilingual faculty advisor, Fernando Diaz, I sought to reassure them.

Diaz shared an opinion piece from Post columnist David Von Drehle about his late wife, their love story and what she’d make of the sharp turn on election night when we began to see that America had chosen Trump again.

I decided to tell my student reporters what I planned to tell my three young Black sons, immigrants from a Muslim country.

“Be brave,” I told them just before 6 a.m. in our newsroom Slack channel. And then a little bit later, “as soon as your eyes flutter open and you process and absorb the news, we need to get to work. Channel whatever you are feeling into turning on your flashlight and shining it brightly. That is our job. That is what we can do.”

Jackie Spinner is a professor at Columbia College Chicago and the faculty advisor to the Columbia Chronicle. She is the editor of GJR.

- ‘Sorry, AP Chem’: How student media at one Missouri high school covered a walkout to protest ICE

- News analysis: Missourians take leading roles in Trump’s ‘weaponization’ of the Justice Department and election denial

- Commentary: Stars and Stripes’ legacy of editorial independence shows value of a free press

- News analysis: Trump’s handling of Minnesota investigations defies time-tested procedures and looks like a ‘cover-up in plain sight’

- St. Louis KDHX-FM radio disappears, but alums stage CRSTL comeback