Joseph Pulitzer was one of America’s great newspaper publishers, but few people today know much about him. When we first decided to make a documentary about the 19th century publisher and American media icon – Joseph Pulitzer: Voice of the People (which aired on PBS in April, 2019), we were faced with a daunting task. Filmmakers depend on images and there were only a handful of Pulitzer images for us to work with. Aside from the eponymous prizes, Pulitzer was the publisher who took on a popular President and who defiantly helmed the New York World and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

We had to recreate his paper The World in ways we couldn’t have imagined–to give a sense of how Pulitzer and his editors produced the most modern of newspapers and gave the paper the lively appeal that it had when the eye swept down, over and across the page. We wanted dramatic camera moves and stillness, moves into focus on musicians playing a favorite Schubert composition for Pulitzer even as he despaired over the loss of his favored daughter Lucille on New Year’s Eve of 1898.

But it was challenging figuring out how to put these pieces together and where to start. We knew, in making the film, that we had to take an old story and meld it to the breaking news of today – the politics that demand that we connect the storms and world-changing events of a bygone era.

It started with a conversation between Bob and me in 2013 and then with interviews with a small band of excellent talkers/thinkers – Pulitzer’s biographer James McGrath Morris – who knew every nook and cranny of material about the man and his paper, and an interview with author Nicholson Baker. Baker wrote Doublefold, about the assassination by microfilm of nearly all of our nation’s newspapers. He also personally saved the last paper copies of Pulitzer’s World and dozens of other significant newspapers from destruction when the British Library auctioned them all off to the highest bidder. We also got help from author Chris Daly, whose book Covering America: A Narrative History of a Nation’s Journalism, succinctly and elegantly told the story of our newspapers and Pulitzer’s central role in modernizing the newspaper. And author and professor Andie Tucher articulated with great enthusiasm how Pulitzer’s daily became the immigrant paper, the people’s paper.

We met Chris Daly at his home in the Boston area in early 2015– with a few lights, a camera and mics. The intimacy of our shot put Daly at ease. Not certian this would be the real shoot rather than a warm up, he was spontaneous in describing the world of Pulitzer. The natural light streaming into his living room was perfect for the tone of the film we were looking for.

For Baker’s shoot, we went to his home in Maine in the fall of 2015 and also filmed in the warehouse near his home, where Nicholson preserved Pulitzer’s paper – photographing it himself with a large format camera– all work that ended up in his and his wife Margaret Brentano’s masterly The World on Sunday (Bulfinch Press, 2005), another prime source for the film. The same personal attention that Baker and Brentano gave to the newspaper is what we tried to give the couple as we sat and listened to Baker, an eloquent talker and writer who effortlessly spun out the story of why he loves Joseph Pulitzer, why he and Brentano took the time and trouble and enormous expense to create that wonderful book and why Pulitzer’s paper was such a huge success. The newspaper brilliantly and incisively explored the political stories of the day but also had sections on home etiquette, on sports, and on the daily lives of immigrants.

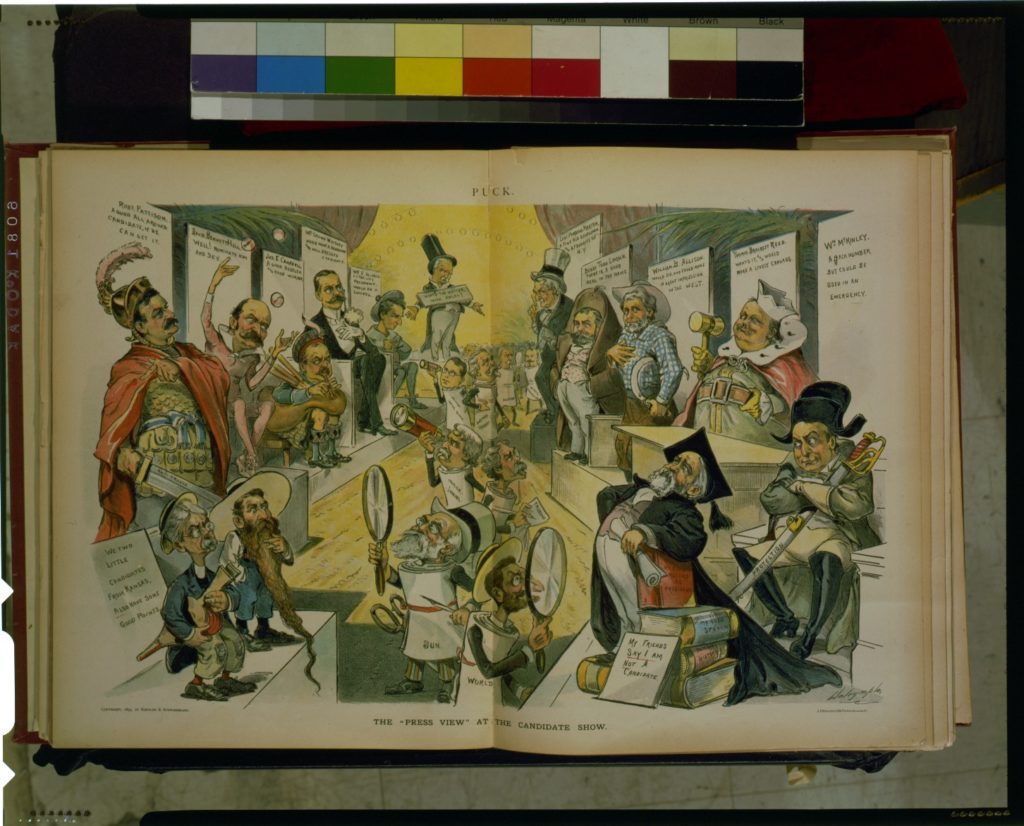

While our early work was completed with a skeleton crew, we recognized when to bring in the big guns and hired one of the best in the business, Wolfgang Held, for our shoot at the Duke Archives. That’s where Pulitzer’s paper – a 30-year daily run of it – is housed in temperature and humidity controlled archival preservation mode. Wolfgang brought in a full crew, two cameras – and the assistance and accommodation of the staff at the Rubinstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library made it [the shoot] all possible. Baker flew in to describe the newspaper page-by-page – to note the political thunderbolts and the intimate idiosyncrasies – such as the Roly–Poly’s – cut out action figures for kids — sheet music of the era’s hits and dress patterns that made the nickel Sunday paper indispensable to New Yorkers and, soon, the entire country.

By talking to and filming interviews with our cast of characters – intimate, lengthy discussions – and by reading all the books we could find to illuminate the story, we were on our way. We collaborated with editor Ramón Rivera Moret, whose thoughtfulness and nuanced storytelling gifts gave us the backbone of a through-line and who made the second-by-second decisions in which every transition made sense.

We took trips to St. Louis where Pulitzer got his start and where we filmed at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch –Pulitzer’s first English language paper and first great success— and then interviewed (on the cutting room floor) photographers David Carson and Robert Cohen and photo editor Lynden Steele who enlarged and updated the Pulitzer saga with their wrenching 2015 Pulitzer Prize winning photographs of the protests following the Michael Brown killing in Ferguson, Missouri.

We relied on the archival work of a half dozen superb researchers, Pru Ardnt and Susan Hormuth and our associate producer Clare Redden, who found images that brought to life Pulitzer’s foreign travels with hand-tinted color postcards. The archive in Pulitzer’s hometown of Mako sent us evocative images from the turn of the century, and the filmmaker Borka Péter provided footage of Mako today. Andras Csillag, a Hungarian scholar of Pulitzer, filled in details of his early life.

But our story still lacked vitality and visual substance and drama. We needed a big set piece to truly set the story in motion and a way to tell the story of a dead man with only twenty or so images. Despite some ambivalence about recreations, one day our researcher tilted his head at an angle just as I was looking at our meager number of stills and it struck me that he looked exactly like a young Pulitzer, down to the shading and shape of his beard. Aha! Daniel Witkin became our young Pulitzer and we decided to film him getting a 19th century eye exam with our optometry expert Daniel Albert. The results of this shoot convinced us to try another with Pulitzer reading Dickens to learn English, then playing chess against himself and then writing a love letter to Kate Davis, his bride-to-be. Master calligrapher Ted Kadin lent his talents to recreating the love letter. We filmed as Daniel Witkin sat poised with the moving pen. The excellent results of these shoots – expertly shot in a hurry by Wolfgang— led to our biggest gamble.

Producer Andrea Miller started looking for a yacht to film, that was period accurate and close to the mammoth size — over 300 ft. long (only JP Morgan had a bigger one) — to film and which we could afford. The generosity of Robert McNeil who had restored a steam yacht called the Cangarda provided a way to visually extend our story – giving Pulitzer an emotional life embodied by an actor our casting director Adrienne Stern found. In his first role – Paul Grossman, a writer and teacher in New York, nailed it. We spent two days in Maine with Grossman (silently) playing an older Pulitzer look-alike, along with his secretaries, and a quartet of musicians on-board. Sounds simple, right? Until you figure in plane travel, ferry schedules, changeable weather, and multiple period costume changes. Then there was the issue of recreating 1890’s newspapers so that you could hold them in your hands without them falling apart – thank you fabricator Renate Spiegler. And loads of equipment and trunks of clothing expertly selected by Asa Thornton.

It goes without saying that there was nothing in our original budget for this budget-breaking extravagance. But, as filmmakers around the world know, a film makes demands on the director just as a director makes demands on a film.

The weather cooperated as did all members of the crew, and Robert McNeil had us all stay in his guest house in Isleboro, Maine, with his personal chef and boat captain at our service. There were multiple mini-dramas – drifting off in a rowboat into an impenetrable fog, sun, tides and changeable weather. But we persevered.

Only days before our yacht shoot we realized the overwhelming significance of the Panama Canal story to our film – The drama of a lone blind publisher taking on a President become exceedingly relevant – Pulitzer used the term “fake news” 100 years ago – the first use of the term we found, though of course fake news is as old as The Odyssey, we suppose.

Then we added voices of superlative talkers – authors David Nasaw, Elisabeth Gitter, Hasia Diner, Dan Czitrom, Nancy Tomes, David Redden and others such as optometry historian Daniel Albert who himself played a role in our recreations, using the tools of the 1880’s to diagnose Pulitzer’s detached retina.

Later Liev Schreiber signed on to eloquently speak Pulitzer’s words with an immigrant’s accent. Tim Blake Nelson evocatively recreated Teddy Roosevelt – and our other superlative actors added their own distinctive talents – Adam Driver as the narrator, Rachel Brosnahan as Nellie Bly, Lauren Ambrose as Kate Davis, Hugh Dancy as Pulitzer’s secretary Alleyne Ireland and others.

The film, which took five years to complete from that initial conversation Bob and I had, was funded through contributions from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Carnegie Corporation, Roxanne and Scott Bok as well as the Berk Foundation, Norman Pearlstine and Jane Boon and other individuals and American Masters and PBS gave their invaluable support.

The film took 18 months to edit, with friendly (mostly) arguments over words and structure and music, requiring the writing and rewriting and rewriting of sentences to give meaning and nuance to one man’s incredible life journey.

In the end, Pulitzer proved to be that most contemporary of stories, a slap in the face reminder of how history repeats itself and a wake-up call for the need of a free press to preserve our quite fragile democracy.

Oren Rudavsky is the director of such films as Hiding and Seeking, Colliding Dreams, The Treatment and A Life Apart: Hasidism in America. Robert Seidman is the writer or co-writer of Billy Strayhorn: Lush Life, Margaret Mead, A Life Apart and the recent novel Moments Observed. Joseph Pulitzer: Voice of the People has just been nominated for an Emmy Award. This story first appeared in the summer print issue of Gateway Journalism Review.