Send in the Clowns: On the MSNBC-Mitt Romney flap

During the last days of 2013, a controversy erupted on MSNBC when a panel of comedians on the Melissa Harris-Perry show poked fun at a photograph showing Mitt Romney’s adopted African-American grandson sitting on the former presidential candidate’s knee surrounded by the rest of his white family members.

“One of these things is not like the others, one of these things just isn’t the same,” sang actress Pia Glenn. The other guests provided humor on the same puerile level. It’s not necessary to be conservative or right-wing to find the host’s and her guests’ performance on the “lean forward” channel dumb and offensive.

The customary five-act drama has, by now, become familiarly silly and meaningless.

Act I: Viewers witness an offense or insult to a group or person by a “personality” or celebrity.

Act II: A wave of outrage floods the internet.

Act III: The offending party issues an apology.

Act IV: The network responds by a) accepting the apology; b) suspending the perpetrator from

future appearances for a period of time, or c) fires him or her.

Act V: Media critics and columnists analyze and interpret the play and inform us “what it means.”

In this case, the last act was “what’s not the same” and doesn’t “belong with the others.” This flap, as others at MSNBC, Fox News or CNN, has very little to do with journalism. The hosts of TV cable news shows and their regular guests do not practice journalism. They are well-paid entertainers, engaged to do what television exists to do: to sell and to distract. They sell themselves and their “expertise,” and in between bouts of self-promotion and hectoring, each network sells the products or services of sponsors who make such shows possible. (CNN and Fox do send camera crews and reporters to cover natural and man-made disasters, and provide occasional breaks in the chatter.)

NYT columnist David Brooks complained that “on cable TV hardly anyone is talking about values and culture.” The boys and girls who host MSNBC’s talk shows are gossips with an attitude, as the bunch on the Harris-Perry program showed us. And their colleagues, while making noise about political and social issues in America, can’t make value judgments about what is good, proper or worthwhile. Once religion, philosophy, history—even ideology –inspired such judgments. Cable news talk is obsessed instead with whacking the opposition in a constant battle for ratings and money. The more outrageous the jokes and more frequent the hits, the better are the chances of besting rival talk shows.

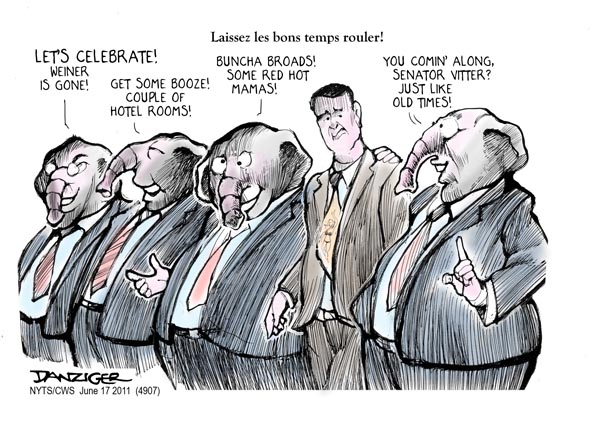

That’s what the Harris-Perry gang was doing: out-performing their competitors by going lower and dumber. They missed their target and were forced to apologize for a tactical business blunder. If you’re going to offend, pick carefully who it’s going to be. They should have stuck to the likes of Anthony Weiner or Eliot Spitzer, whom only sex-addicted viewers might have defended.

Media critics think they cannot ignore such flaps. It might be time, then, to take the category of the “talk show” out of the news division and place it where it belongs: into the infotainment segment. Then those who write about television could organize an annual awards show for best performances in infotainment. Ms. Harris-Perry could qualify as a nominee for “the most wrenching and lachrymose apology” of the year; her colleague Al Sharpton for the best faux outrage exhibited in a single segment; Fox News’s Sean Hannity for best faux astonishment at the crimes against America by the Obama administration.

Journalism? It breaks out occasionally on TV. But if you want to know what it could be, listen to tapes of Edward R. Murrow reporting the German bombing Blitz on London for CBS or read Sidney Schanberg’s dispatches from Cambodia as our B-52s carpet-bombed the neutral little country. There were columnists, too, whose analysis was well-informed and thoughtful, and too complex and long to fit into three-minute segments on TV talk. Watch a conversation on YouTube between conservative William Buckley and liberal Gore Vidal from the Fifties or Sixties. Both were educated and articulate, and they listened to each other and responded. Heatedly, at times, but they addressed the substantive matters raised by the other. They engaged in serious conversation about serious issues.

That’s entertainment? The tyranny of entertainment was not yet upon the land. But the business of TV soon established it. As the late writer for The New Yorker George Trow observed after he watched one of the early talk shows: “The Germans lost World War II. Television won.”