The Alden effect – Nonprofit news on the rise

In its voracious drive to apparently consume as many U.S. newspapers as possible, the so-called vulture capitalist Alden Global Capital recently bought the San Diego Union Tribune and a group of associated newsrooms in southern California.

Reports on the purchase focused on the inevitable results of Alden Global acquiring newsrooms: immediate decimation of the staff, loss of office space, and the predictable ensuing loss of news coverage and service to the community.

But what is often not noted is how Alden Global is a call to arms for the creation or expansion of alternative, and often nonprofit newsrooms. A call to arms that should have been sounded years ago.

Call it the Alden effect.

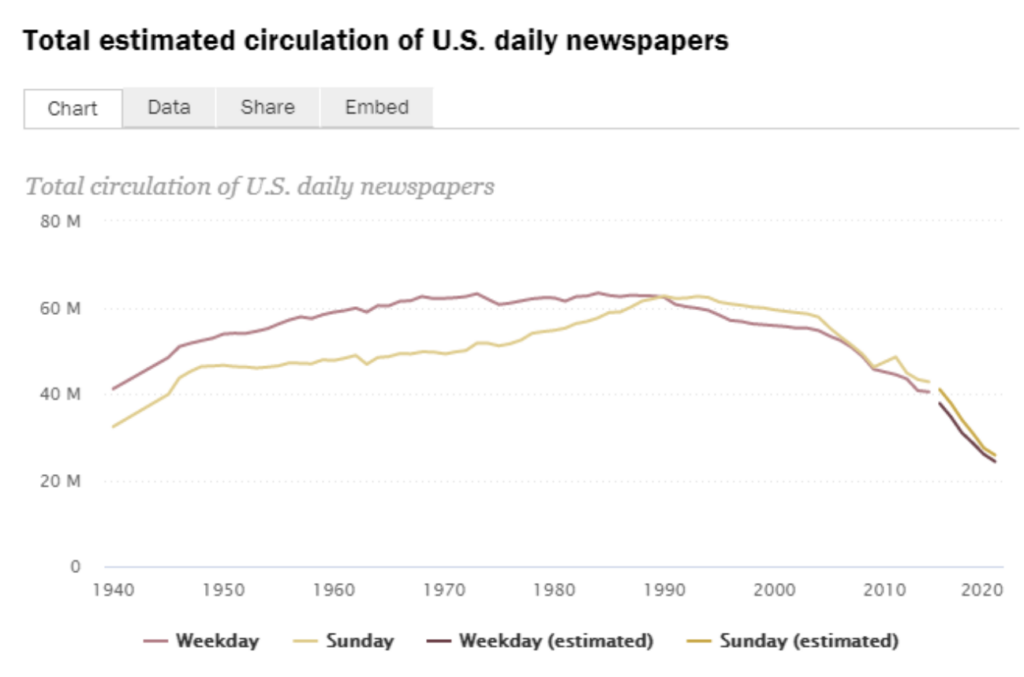

Alden’s brazen and brutal harvesting of a disrupted and distressed news industry has made clear the long death spiral of newspapers and legacy media. And it has made clear how a new business model for journalism (usually a nonprofit model or a public benefit corporation) is needed and how independent digital newsrooms need to form deeper alliances.

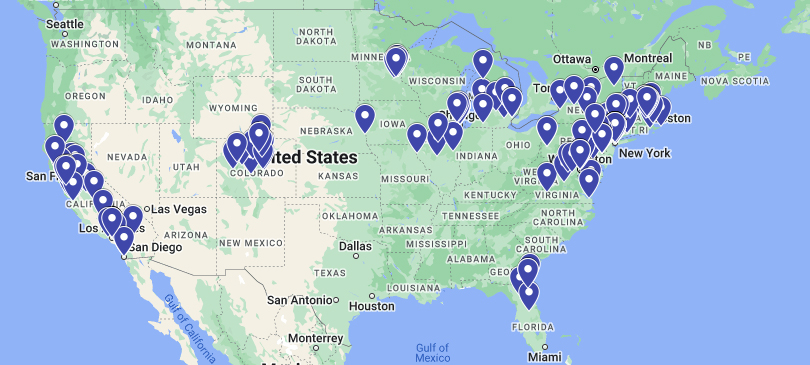

In San Diego, two such newsrooms, the Voice of San Diego, which has largely focused on overall community reporting, and inewsource, which concentrates on investigative reporting, have had a somewhat distant relationship over the past decade. But after the Alden announcement they began discussions on collaborating to counter the loss of news coverage by the Union Tribune.

The founder and head of inewsource, Lorie Hearn, said in an interview recently that the American Journalism Project, which supports local news initiatives across the nation, will not only back the efforts of the two newsrooms, but also fund a “landscape assessment” in the San Diego region that will analyze the demographics, the existing news ecosystem, and a community listening tour.

Hearn said, “The idea is to find a solution to the big problem — the slow bleed that has been happening here for years and is now accelerated with the Alden purchase.”

In an Atlantic Monthly article about Alden Global in 2021, McKay Coppins wrote, “What threatens local newspapers now is not just digital disruption or abstract market forces. They’re being targeted by investors who have figured out how to get rich by strip-mining local-news outfits. The model is simple: Gut the staff, sell the real estate, jack up subscription prices, and wring out as much cash as possible out of the enterprise until eventually enough readers cancel their subscriptions that the paper folds, or is reduced to a desiccated husk of its former self.”

While the actions of Alden, which had become the second largest newspaper chain in the U.S. with the Tribune purchase, might have appeared to be a new phenomenon, the news industry had long been the target of financial predators. In writing the second edition of “The Vanishing Newspaper” in 2009, Philip Meyer described the business strategy as “harvesting:”

“A stagnant industry’s market position is harvested by raising prices and lowering quality, trusting that customers will continue to be attracted by the brand name rather than the substance for which the brand once stood”. He went on to note “this is a nonrenewable, take the money and run strategy”.

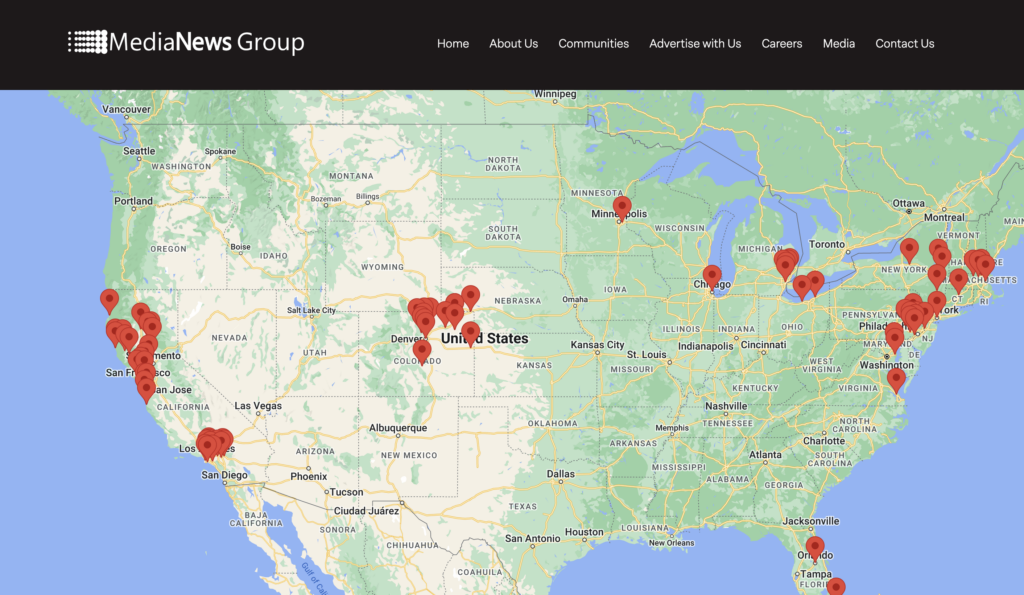

Alden made one of its biggest moves by acquiring the debt-ridden MediaNews Group in 2010. The MediaNews Group was another example of newspaper companies taking on extreme amounts of debt as they purchased newspapers while circulation and revenue fell despite the cost-cutting through consolidation. (Alden’s chain of newspapers operates under the MediaNews Group.)

The head of MediaNews Group, Dean Singleton, who once predicted that there soon would be only three newspaper chains – and his MediaNews would be one of them – eventually was also crushed by the debt his company had taken on and filed for bankruptcy in 2010. It was Alden that then took a large share of the stock after the company came out of bankruptcy and by 2011 Singleton had been effectively removed from the leadership team.

In a prescient article in Nieman Labs in 2011 by Martin Langeveld, headlined, “The shakeup at MediaNews: Why it could be the leadup to a massive newspaper consolidation”, Langeveld, who had been a publisher for MediaNews, predicted various mergers involving Alden that eventually took place. He noted that Alden had been building up its newspaper holdings through the Alden Global Distressed Opportunities Fund, “which it launched in 2008 and which is now worth nearly $3 billion.”

Langeveld concluded by writing, “It’s really the last hope for the newspaper business, but a pessimistic view is possible, of course…. Alden’s ultimate interest is in earning a strong return on its investments, not in the future of journalism, so its strategy is at heart a financial one. And, yes, consolidation will come at the cost of jobs.”

In cities, states and regions, the appearance of Alden has quickened overall efforts to create, expand and fund other newsrooms. Simply put, Alden makes transparent how shattered newspapers and their coverage of their communities have been for more than a decade.

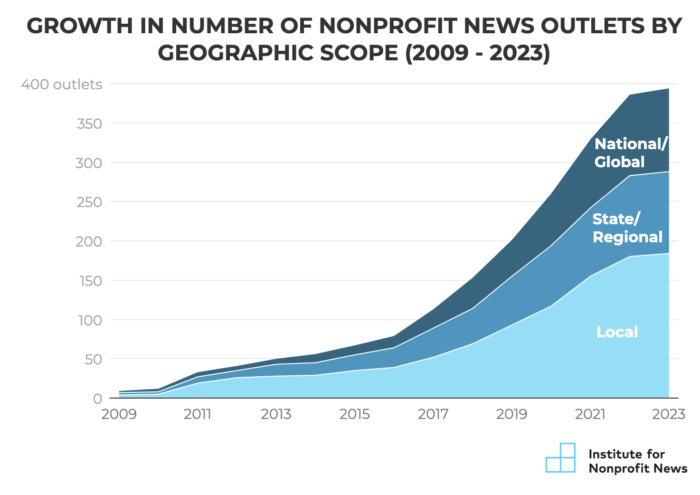

Actually, Alden was not the last hope. Instead, it spurred public recognition of the news crisis and then encouraged a host of funders to direct dollars into new or invigorated newsrooms.

When Alden bought the declining Chicago Tribune in 2021, the vibrant neighborhood-focused non-profit Block Club Chicago had already been in existence for three years. But as the Tribune shed more editors and reporters after the purchase, Block Club received even more recognition and support. Similarly, foundations and donors poured money into other Chicago nonprofit newsrooms to increase local coverage. The acquisition by the nonprofit WBEZ of the struggling commercial Sun Times to form a more robust and dynamic local newsroom completed the sea change in Chicago journalism in response to Alden.

In Baltimore, the creation of the The Baltimore Banner, a nonprofit newsroom, was the direct result of Alden Global’s purchase of the Baltimore Sun (which was part of the Tribune Publishing deal.)

Stewart W. Bainum Jr., a wealthy owner of hotels, had tried to buy the Sun but Alden Global outbid him in May 2021. Bainum was sure Alden would follow its usual practice of cutting staff at the Sun and thus local news (which it did), so in 2022 Bainum created the Banner. At the time, he told the New York Times, “I kept thinking about local news during Covid, sitting here in Maryland, thinking about the dearth of local news.”

The Banner hired some of the experienced reporters laid off by the Sun and Bainum said he hoped to eventually have a newsroom of 100.

The trend of Alden purchases and the resulting surge of start-ups, collaborations and increased investments started with little fanfare when Alden acquired the MediaNews Group. Under Singleton, the MediaNews Group created a large chain of newspapers that included the Denver Post, the St. Paul Pioneer Press, and the Mercury News based in San Jose, California.

Denver had already seen the closing of the Rocky Mountain News in February 2009. With Alden coming in the usual cuts hit the Post. A newsroom once boasting hundreds of editors and reporters was reduced to a few dozen over the next decade. In a direct rebuff to Alden a group of journalists in 2018 left the Post and started The Colorado Sun, which has turned into a public benefit corporation, which is a for-profit company incorporated with a public mission. It states on its website, “Every dollar we receive goes directly toward supporting the journalism we produce. Period.”

But that was only one part of the effort to preserve and grow local news in Colorado. The Colorado News Collaborative News Lab currently involves more than 180 news organizations, profit and nonprofit, and in every medium.

Laura Frank, the executive director of the lab and a major player in the evolution of nonprofit newsrooms in the U.S., said a recent interview that the lab was even collaborating with “folks with Alden” who are trying to keep local news alive from the inside of the company.

“The tragedy of Alden coming in has fed the fire of ingenuity in news,” Frank said.

In Minnesota, both major newspapers had been failing financially when Alden came on the scene in 2010 and took control of The Pioneer Press in St. Paul and implemented its usual playbook of cuts. But a wealthy investor, Glen Taylor, stepped up to buy the Minneapolis Star-Tribune and it has thrived under his ownership.

In California, the Alden purchases before the San Diego buy has spawned a wide variety of newsrooms throughout the state. Alden had acquired the San Jose Mercury and other Bay Area newsrooms through the MediaNews acquisition and by 2015 CalMatters was founded, it said, to create a newsroom “to fill the gap left by left by a shrinking press corps,” much of which could be attributed to Alden. It says it now has more than 40 experienced journalists and a team of product and revenue professionals. Its leader is now Neal Chase, who left his executive job at Alden’s Bay Area papers to join CalMatters in 2018.

Meanwhile, the San Jose Spotlight started up in 2019 to replenish the political and business reporting in the city. It stated, “Our mission is to change the face of local journalism by building a community-supported newsroom that ignites civic engagement, educates citizens and strengthens our democracy.” It now is partnering with the Oakland-based Post News Group, which consists of eight Black and Spanish language newspapers in Northern California, to launch another newsroom in Santa Clara County.

Indeed, the Alden Effect appears not only to result in more independent, community driven newsrooms, but also newsrooms that are more diverse and enterprising than those of the legacy media.

“There’s a new dawn in local news. It’s rising in many of the communities where remote corporate owners or investors hollowed out a local newsroom, closed a local newspaper or don’t attempt to serve everyone,” said Sue Cross, the chief executive officer of the Institute for Nonprofit News.

Cross said that increasingly people are fighting back and saving local news or reinventing it in a way that fits for their communities.

“People are deciding their local news should be just that: local. They see news is a way to build and connect their community — economically, socially, civically,” she said. “And this is leading to new partnerships. Journalists and community groups, civic leaders and philanthropists are working together to create new kinds of newsrooms — locally led, community-centered, more inclusive, and dedicated to building trust by being open about who pays for the local reporting and how they do it. The nonprofit newsrooms are nonpartisan, and they are forming in all kinds of communities – red, blue and everything in between.”

She said those newsrooms are supported largely by their own communities, but they also “can tap into nationwide networks of investigative and specialized reporting centers, news tech hubs, legal and business resources that can now enable local newsrooms to do more than they could on their own.”

“Together, this kind of local support and national networks of nonprofit news resources are changing the future of local news,” Cross said.

Brant Houston is Knight Chair in Investigative Reporting at the University of Illinois