The media and the ‘mistakes were made’ excuse: Time to ask questions

“Anthony has made some terrible mistakes,” a grim-faced Huma Abedin said at a press conference about her husband’s (Anthony Weiner’s) sexting adventures that may wreck the former congressman’s run for mayor of New York. Weiner also described his Internet forays with young women as the underwear-clad “Carlos Danger” as “mistakes.”

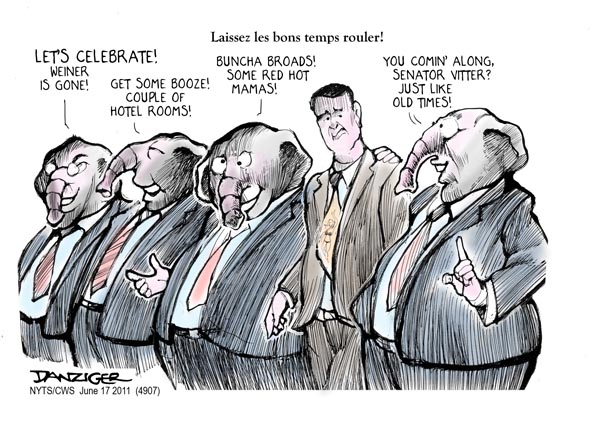

The “mistakes were made” excuse is an old staple among Washington’s scandal-prone politicians, and it’s about time that reporters asked questions that would earn it its well-deserved retirement. What Weiner and more famous politicians before him committed were not “mistakes.” When Bill Clinton was governor of Arkansas and sexually harassed Paula Jones, he was not making a mistake. He wanted, as we used to say in the old days, “have his way” with her. President Kennedy “persuaded” his 19-year-old mistress to engage in a sex act with one of his buddies and White House assistants.

The three men behaved badly and deliberately acted in ways that were immoral, bullying or dishonest. Their behaviors were not mistakes, but acts and words meant for gain and hidden for a while by deception. Or take the former governor of New York, Eliot Spitzer, who spent $80,000 on hookers. The pleasure he found with them was not result of a mistake. He never expressed buyer’s remorse, only regret that his purchases had been revealed.

If Weiner had wanted to buy a Snickers bar but grabbed a Milky Way at the news kiosk, that would have been a mistake. If Silda Spitzer had sent Eliot out to get a carton of fat-free half-and-half and he came home with a regular one, that would have been his mistake. None of the politicians mentioned committed such mistakes when surfing for sex or harassing a state employee. A mistake is an unintentional error, sometimes the result of misunderstanding, misconception or inattention.

Whenever a politician and his spouse describe “mistakes” that were made, reporters need to ask why what they did can be defined as a mistake. And unless you’re working with the Bill (“whatever the definition of ‘is’ is”) Clinton stylebook, hardly any of their transgressions would qualify as mistakes in the dictionary.

Reporters might want to follow the advice of that wise and word-weary German poet Bert Brecht: “Great men should be honored, but they should not be believed.” So, reporters from Maine to California, start asking why and how those “mistakes made” really are mistakes. The answers could be funnier than the jokes on late-night television.

Salamon taught German literature and culture at several East Coast colleges, and served as staff reporter for the St. Louis Business Journal and as senior editor for Defense Systems Review. He has published three academic books and contributed articles to the Washington Post and the American Conservative.