U.S. lags other nations in regulating AI

The surge in use and chatter around artificial intelligence after ChatGPT’s release six months ago has increased awareness and concern of the technology’s rapid progress. Now, the United States government faces the question of how to regulate this potentially uncontrollable technology—something it has fallen behind on before.

AI innovators and experts Sam Altman, the chief executive of OpenAI, Gary Marcus, professor emeritus at New York University and Christina Montgomery, vice president and chief privacy and trust officer of IBM, testified to many ideas on how the United States could proceed with regulation in a Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology, and the Law hearing last month. However, Illinois Sen. Dick Durbin (D) wondered if Congress was equipped for the task.

“When you look at the record of Congress in dealing with innovation technology and rapid change—we’re not designed for that. In fact, the Senate was not created for that purpose, but just the opposite…We’re going to have to scramble to keep up with the pace of innovation in terms of our government public response to it, but this is a great start,” said Senator Durbin in his opening remarks at the May 16th hearing.

While the fear of losing its grip on AI looms over the Senate subcommittee, AI regulation has already distinguished itself from previous technological innovations, suggesting a promising future. Although AI innovators acknowledged the possible dire consequences and potential threat, the portrayed eagerness to collaborate with the government places some at ease. Whereas previous technological innovators and private sector companies have shut out the government from their innovations, AI leaders seek government intervention immediately.

“What I’m hearing is a ‘stop–before I innovate again’ message. I’m just wondering how we are going to achieve this,” said Durbin.

While Senator Durbin extracted that message from the experts’ testimonies, Altman’s history regarding AI development is not clearly indicative of that mindset. For example, Altman declined to sign the Future of Life Institute’s open letter requesting a six-month pause on AI lab developments of technology stronger than Chat GPT-4. Instead, Altman explained that continued progress and release of the technology will better prepare society for AI’s ever-growing presence.

Altman’s desire for continuous advancement of AI is not necessarily at odds with his concern of the technology’s risk or his awareness of the need for regulation. However, Altman’s perspective may shape the strategies he suggests for AI regulation moving forward.

Current Action for AI Regulation

When the U.S. Senate began the conversation in the subcommittee hearing last month, other governmental bodies both nation-and-world-wide had already begun thinking about AI legislation. According to Stanford University’s 2023 AI Index, 127 countries passed 37 bills into law that refer to AI in 2022. However, with the technology’s ever-growing global presence, countries are starting to move beyond mere reference to AI by proposing legislation to regulate it.

Since its initial proposal for AI regulation in 2021, the European Union has become a global leader through its development of what it calls the “AI Act.” The European Union’s proposed law would be the first of its kind and proposes a “risk-based approach” to regulation.

According to the European Commission’s summary presentation on the Act, the proposed law breaks AI into two categories based on risk: permitted and prohibited uses of the technology. The Act bans prohibited uses—also called “unacceptable risks”—and provides guidelines governing how to use permitted forms of AI. The European Union separates the permitted uses into three additional subcategories: “high-risk,” “AI with specific transparency obligations,” and “minimal or no risk.”

On May 11, 2023, the Internal Market Committee and the Civil Liberties Committee of the European Union adopted a draft negotiating mandate of the Act. After review of the draft, the committees crafted amendments focusing on making AI “human-centric” and “ethical” within Europe.

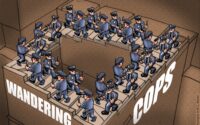

The committees’ amendments expanded the coverage of the Act by adding AI systems to the unacceptable—and therefore prohibited—risk category. Among the additions were: real-time biometric identification systems, predictive policing systems, and emotion recognition systems.

Additionally, the committees added AI technologies potentially posing threats against European citizens’ “health, safety, fundamental rights, and environment” to its “high-risk” category. Under the proposed law, AI technologies within these categories must be subject to human oversight, include logging features for traceability, and use high-quality training.

Finally, the committees added more intensive transparency requirements for AI models. Publishing copyrighted data used for training, disclosing AI-generated content, and designing models without capabilities to create illegal content are among those additional requirements.

Most recently, on June 14, 2023, the European Parliament adopted its own negotiating position of the European Commission’s AI Act proposal. In comparison to the Commission’s proposal, the European Parliament’s position appears narrower and more restrictive. Moving forward, the European Parliament, Commission, and Council must reconcile the differences in their proposals to turn the Act into law. Conversations between the branches are expected to continue for the remainder of this year.

Although the European Union is the closest to finalizing binding legislation regarding AI regulation, it is just one of many countries taking steps to manage AI. Brazil, for example, drafted and presented a report on AI regulation in December of 2022 that now serves as the foundation for the Brazilian Senate’s further action. Also in 2022, Canada’s government drafted the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act as part of the Digital Charter Implementation Act; the bill still awaits approval from the Canadian Senate.

In October of 2022, the White House Office of Science and Technology (OSTP) released the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights—a white paper published to “support the development of policies and practices that protect civil rights and promote democratic values” as the presence of automated systems increases. The AI Bill of Rights includes five guiding principles and practices crafted for Americans’s right to privacy and in light of their everyday experiences with AI technology.

The five principles include: Safe and Effective Systems, Algorithmic Discrimination Protections, Data Privacy, Notice and Explanation, and Human Alternatives, Consideration, and Fallback. Each of the five principles prioritizes proactive and ongoing action by AI innovators to ensure the safety of Americans. Each principle expects automated systems to take actions such as consultations, collections of representative data, implementations of privacy-preserving security, and accessible, clear communications. While these principles offer a framework for how individuals, corporations, and governments should proceed in the face of AI’s impact, they do not offer binding legislation.

The actions taken by governments around the world suggest that many countries envision AI regulation through lawmaking within their respective countries. But, if the technologies are used worldwide, should the regulation of them be addressed on a global scale instead?

Suggestions for Future Regulatory Action

Based on the current governmental action worldwide AI many experts say is evident that AI regulation is needed on a global and national scale. But, the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology and the Law still does not know what is the most effective way to approach the challenge.

Chief Privacy and Trust Officer of IBM Christina Montgomery suggested Congress adopt a “precision regulation” approach to AI in her testimony to the Senate subcommittee. According to Montgomery, precision regulation “strikes an appropriate balance” between protection and preservation of Americans and their environments. However, regardless of the AI regulation format, Montgomery hopes that transparency and clarity are at the forefront of Congress’s regulation.

The United States could seek the expertise of the Federal Trade Commission or Federal Communications Commission, however, AI is and will be an essential piece of the nation’s future, said Professor Marcus to the Senate Judiciary Committee. Thus, Marcus believes it is in the nation’s best interest to create a new government organization to specifically address the risks and information of AI. One organization, Marcus suggested, could be a cabinet-level organization employing technological expertise and coordination for such efforts.

Despite the importance of these national efforts, the expansive nature of AI suggests a need for international regulation through an international agency, both Marcus and Altman said. Yet, the international dynamics and relationships pose difficulties, even though the issue is so pressing, Marcus said. However, the United States could lead and control AI on an international level if it possessed control over the companies and products dealing with the production of the technology, said Altman.

How AI Can be Regulated

Amidst all of the proposed laws, initiatives and open letters, there are six ways posing the most viability for AI regulation, according to the MIT Technology Review. Each of the proposed solutions analyzed by MIT approaches AI regulation on an international scale—similar to Marcus and Altman’s regulatory vision presented in their testimonies. Of the six approaches, the European Union’s AI Act, the Organization for Economic Development’s (OCED) principles and the International Organization for Standardization’s risk-standards appear most influential. Yet, each regulatory approach is not without its faults.

According to the MIT Technology Review, although the European Union’s AI Act is the most effective option, many provisions are “highly controversial” due to their restrictive nature. Thus, it is likely tech companies will lobby against the Act and increase the proposed law’s time in the legislative system.

The research and analysis of global AI experts help to shape the OCED’s principles and look like a “sort of constitution for western AI policy,” according to the MIT Technology Review. However, these principles are non-binding ideals that prioritize economic growth over regulatory solutions. As a result, difficulty may arise in interpreting such ideals into enforceable law that address all risks.

The International Organization for Standardization’s risk-standards are more practical and regulation-focused than the OCED’s principles. Additionally, the MIT Technology Review stated that these standards help simplify the advanced technological elements of AI that many regulators struggle with. Yet, the International Organization for Standardization’s assessments appear overboard, leaving specific areas of AI regulation left for interpretation.

As stated in the MIT Technology Review, the European Union’s AI Act may ultimately become the “world’s de-facto AI regulation” due to the international business and trade relationships. Even so, the U.S government remains challenged by its choice of if and how it will regulate AI.

Although the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission regulate most digital platforms in the United States, Senators Michael Bennet and Senator Peter Welch agree with Altman and Marcus that AI requires a new federal agency. Thus, the two senators drafted the “Digital Platform Commission Act,” proposing a new federal commission to assist in AI regulation.

“Technology is moving quicker than Congress could ever hope to keep up with. We need an expert federal agency that can stand up for the American people and ensure AI tools and digital platforms operate in the public interest,” said Bennet.

Once created, the commission may approach regulation in a myriad of ways. One option is to regulate via licensing, according to Brookings. For example, the Federal Communications Commission licenses commercial and noncommercial uses of radio, satellite communications, and mobile device services. Accordingly, Bennet and Welch’s proposed “Digital Platform Commission” may adopt such licensing strategies as it regulates AI.

Sen. Welch puts it this way: “Big Tech has enormous influence on every aspect of our society, from the way we work and the media we consume to our mental health and wellbeing. For far too long, these companies have largely escaped regulatory scrutiny, but that can’t continue. It’s time to establish an independent agency to provide comprehensive oversight of social media companies.”

Jane Wiertel is a rising second-year law student at Case Western Reserve University and Squire Patton Boggs fellow at the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.