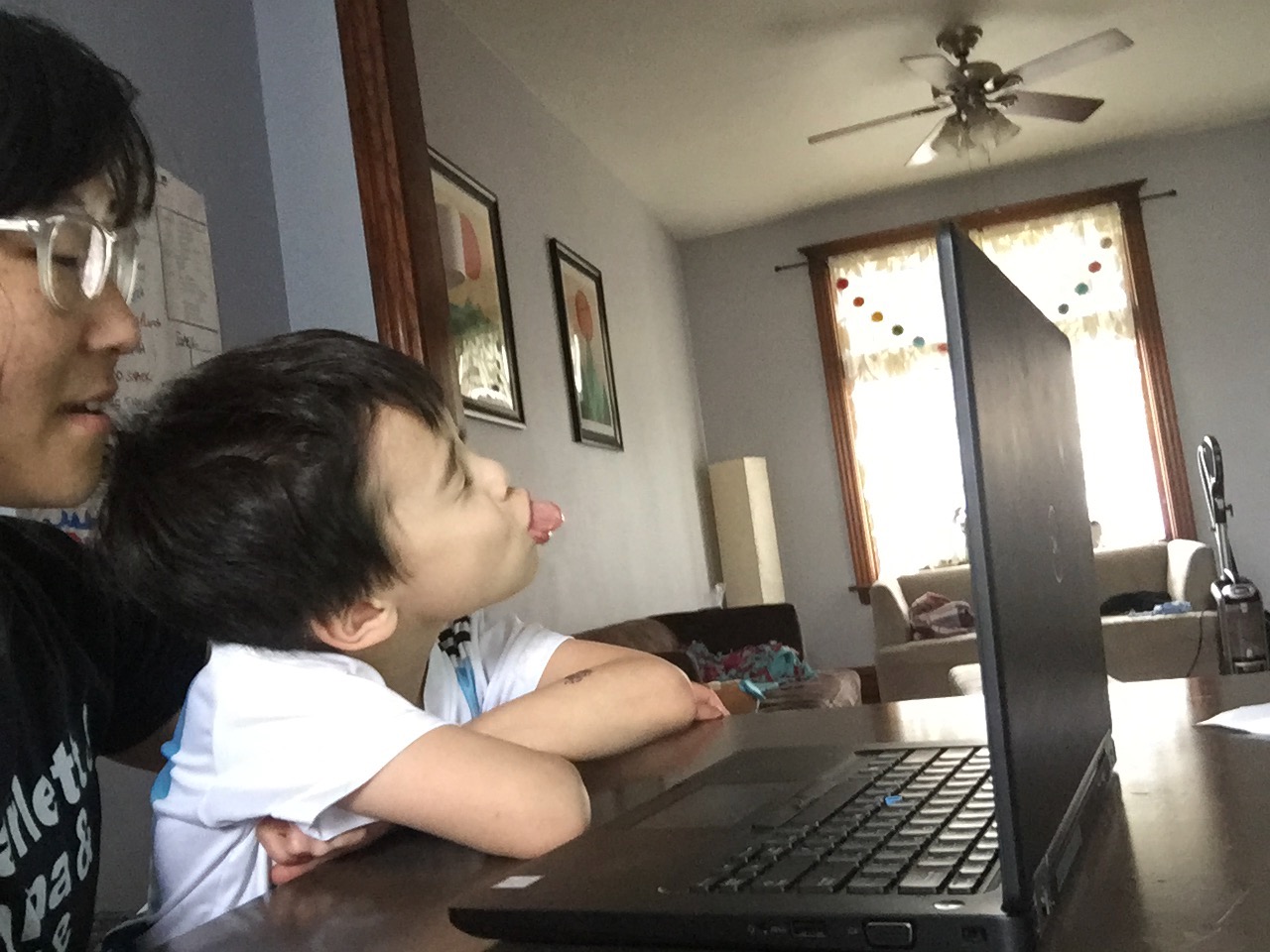

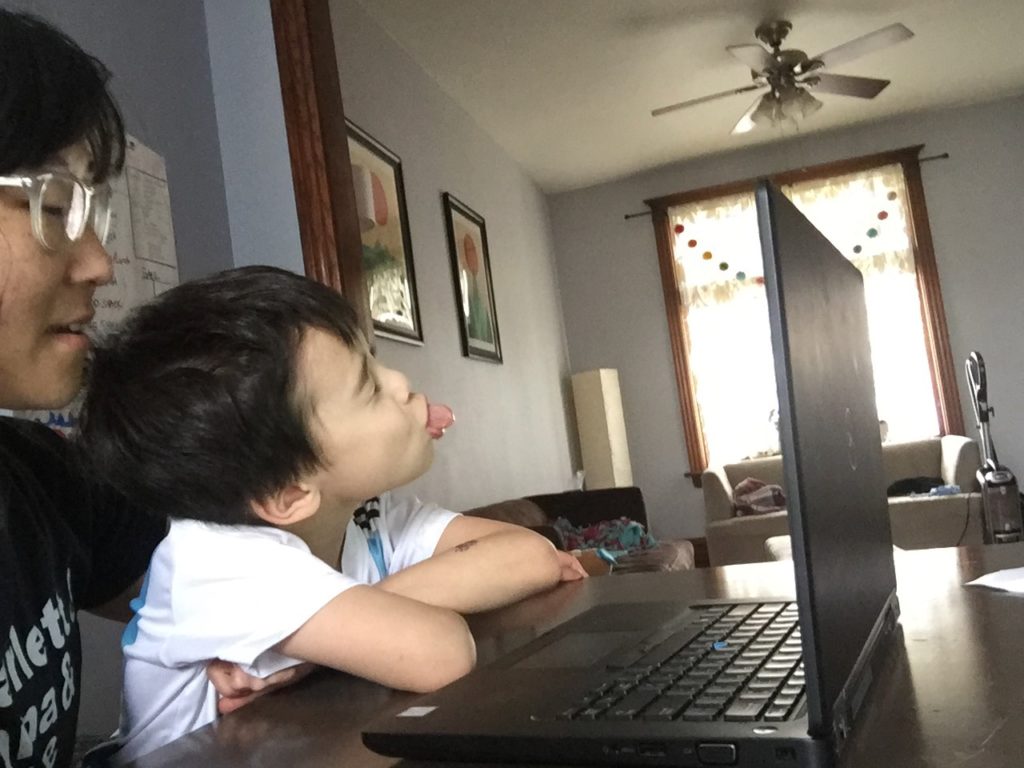

Like many journalists in the early months of the pandemic, Susie An was mostly working from home. Draped in a blanket, her radio equipment propped on a big box of diapers, the education reporter at WBEZ in Chicago voiced her news stories and features from a closet. With schools and daycares closed, her days were hectic working from home with her sons, ages 7 and 3. “My children are quite loud and, shall we say, creative with their play,” she said. “There were times when I was on an interview and my husband was in a meeting. That’s when our children broke a lot of things, made big messes or got hurt.”

WBEZ reporter Susie An works from home with her two young sons during the pandemic.

In Atlanta, Cynthia DuBose, the managing editor for audience engagement at McClatchy, had to jump from her own work video calls to helping her daughters log into their virtual classrooms for school. “I remember in those first weeks, waking early, working, getting the girls up and busy, working until 6, cooking dinner, spending family time, having bedtime and working again from 8 until I fell asleep,” said DuBose, whose daughters are 6 and 9.

Meanwhile, Bethany Erickson, the digital editor for People Newspapers in Dallas, found herself working later and later to account for the breaks she took during the workday to help her 10-year-old son with his fourth grade math, which, she noted, is nothing like the math she did in fourth grade.

“I’m always just at that edge of kind of tired and actually exhausted,” Erickson said.

For many working moms in journalism, the past year of juggling job responsibilities and parenting–often in the same shared space, was one of their toughest, even if it also produced unexpected gifts like reclaiming time from long commutes, earlier dinner times with their families and just being around more.

Erickson’s son, who is autistic, started pitching stories after watching his mom work from home. “We worked in the same room a lot, and he got to see what steps go into writing a news story,” she said. He started asking questions and has even written a story and two op-eds for our papers this year. I don’t know that he would have been as interested in improving his writing if we hadn’t had this time together.”

Women make up nearly half of the total workforce in media and entertainment, although most of them are concentrated in entry-level positions, according to a 2020 report by McKinsey & Company, a global management consulting firm. The pandemic disproportionately affected them, especially if they were also raising children or doing it as a single parent. After all, if you don’t have childcare, it’s hard to drop everything to cover breaking news, and the news didn’t let up last year.

“I felt caught between doing a good job and being a good parent, but failing most days at both,” said An, who also fills in as an news anchor and talk show host at the public radio station. “I do credit my editor with having understanding of the situation and trying not to assign me quick turn news items in the mornings. That was helpful.”

Working dads didn’t escape the additional stresses of the pandemic. More worked from home and either shared or shouldered childcare or household responsibilities during the peak of the stay-at-home orders when nobody, except the most essential of essential workers, were going anywhere. There was a significant shift in parenting roles and involvement for many dads, including journalists. But the fact is that gender inequality remains, both in the workplace and in the home, and working mothers are more likely to scale back their careers or reduce their hours to care for children even outside of a pandemic. One study last year found that the gender inequity worsened, particularly for working mothers of school-age or younger children.

Across the globe, women worried about managing additional responsibilities while at home, a lack of childcare and the potential threat of losing income or jobs. And it wasn’t just the pandemic, with its historic lockdowns and stay-at-home orders. It was the summer of racial reckoning and the protests that swept the world after George Floyd was murdered by a Minnesota police officer. It was the US presidential election.

“I shared with a friend the other day that I am still in shock about 2020,” DuBose said. “It’s almost like I’m in a twilight zone. I lost family and friends, watched in disbelief as part of my beloved Atlanta burned, watched again in disbelief as a man was killed about 30 miles from our home at a Wendy’s parking lot and lived through my Georgia becoming ground zero for an election like none other. And that’s just news.”

Mira Lowe, president of the nonprofit Journalism and Women’s Symposium, said women journalists on the frontlines of covering the pandemic and the social unrest of last summer had to contend with keeping themselves safe while in the field and their loved ones safe when returning home. “Self-care was also a stretch for women juggling the demands of the job and family while working remotely,” she said. “Many of us worked more hours while at home.”

She said one of the biggest challenges for women in journalism, particularly freelancers and entrepreneurs, was loss of income. “For many, writing assignments evaporated and contracts were put on hold,” said Lowe, who is also director of the Innovation News Center at the University of Florida. “Public speaking engagements were cancelled. Book promotions ceased. In some cases, spouses and partners also lost jobs.”

S. Mitra Kalita, a veteran media executive and columnist for Fortune magazine, said the fact that decent health coverage remains anchored to full-time work is a massive roadblock to balance, innovation and flexibility for working moms. “You might say you can turn to Obamacare or the exchange,” she said. “Except that the process of researching, switching and advocating is a whole ‘nother job.”

Women also are often caring for aging parents, not just their children. When the pandemic began, Kallita moved between her parents’ place in New Jersey and her family’s home in Queens. “My father had a second stroke right before lockdown, and I was terrified of him being in a hospital or rehab. So we brought him home,” said Kalita, whose daughters are 9 and 16.

“My parents are in the process of selling their house right now,” she said. “Navigating the property tax breaks for seniors, necessary smoke-alarm inspection before closing and even just asking why their latest prescriptions did not qualify for reimbursement is a massive part of my life and time. I don’t need help from employers with this though. Rather, I think we need to collectively fight to make processes simpler, equitable and accessible. Think of how much invisible labor women like us pour into this.”

With the Delta variant of COVID-19 circulating and children under 12 still ineligible for the vaccine, it’s hard to talk about post-pandemic life in the present. It may yet be months off. But one thing is almost certain. “The pandemic has shown us we can work remotely,” Lowe said. “And so, I think the remote workforce is here to stay. Companies should find ways to embrace it and adapt benefits to support it. Consider flex schedules and policies that allow for a better integration of work and life responsibilities. Continue to incorporate virtual meetings into workflows so that everyone can be included. Focus on self-care strategies, and providing mental health and wellness resources. Invest in virtual and onsite skills-based training to help employees keep their skills sharp. Build online communities or interest groups, i.e. for working mothers, to fuel connection and support.”

Kalita, who left her job as a senior vice president at CNN Digital at the end of 2020 to launch her own media business, said the media industry needs a shift in work cultures toward moms and caregivers. “We will often say someone didn’t want to apply for the bigger job or stay with an organization because of their kids,” said Kalita, who co-founded Epicenter-NYC, a community journalism movement, and URL Media, a network of Black and Brown news outlets. “Instead, we need to be asking how we – as organizations – can better support them to help them ascend or be retained. It puts the commitment to keeping talent on work culture versus trying to shoehorn old methods into new realities.”

DuBose, who worked from home before the pandemic, said she definitely learned that she needs to prioritize self-care, which includes delegating, blocking her calendar and taking a real lunch. “Without it, I’m not sure how I would have survived.”

She also said what 2020 did for race conversations cannot be downplayed. “The events allow me to now have very real conversations with some of my white friends (allies) that I probably would not have before. I know that some events really divided our country but I also believe that for those of us who see the value in listening to gain understanding, 2020 was a game changer.”

Both An, in Illinois, and Erickson, in Texas, plan to continue working remotely part of the time this fall when their children are back in school or daycare. It will be easier, of course, when they are alone at home working.

“Both of my children have been receiving virtual therapy, but will likely do in-person visits starting in the near future,” An said. “I hope there will be good balance and understanding as we transition into that. Also, I hope schools will keep doing the virtual teacher parent conferences. Pre-pandemic, that was nearly 2 hours out of my day for a 15 minute meeting.”

Erickson also was able to negotiate a hybrid schedule starting in August, where she will be in the office three- to four- days a week and working from home one day a week. “My husband was able to negotiate the same, which means we’ll only need to nail down after school care for two-three days a week,” she said.

Kristen Graham, who covers Philadelphia schools for the Inquirer, said she can’t imagine going back to the newsroom full-time again, certainly not eight hours a day, five days a week like she used to. (The Inquirer newsroom is still closed, but employees may return as early as September.)

“Selfishly, I’d love to go back,” she said. “I liked having eight hours where I was just working. But I can’t imagine going back just because I feel that I need more flexibility in my day. I was trying to fit in too much in non-work hours.”

Graham, whose sons are 8 and 5, plans to work from home several days a week. “I’ve found that I’m surprisingly productive when I have my kid at tennis practice, and I’m writing in the car.”

Her editors are both working parents and have not pressured her about returning to the newsroom, she said. “Being a working parent is hard,” Graham said. “Having some flexibility makes it easier.”