When Lisa Rosenberg recently traveled to Croatia, the open-government advocate was prepared to debate the appropriateness of campaign-finance disclosure laws in a formerly Communist regime. But she found little need to persuade.

When Lisa Rosenberg recently traveled to Croatia, the open-government advocate was prepared to debate the appropriateness of campaign-finance disclosure laws in a formerly Communist regime. But she found little need to persuade.

“It was a given that this information had to be made public,” says Rosenberg, a government affairs consultant for the Sunlight Foundation, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit that works to enhance government transparency. “They think that’s so important as an anticorruption measure that it didn’t even occur to them in Croatia that this would have to be private.”

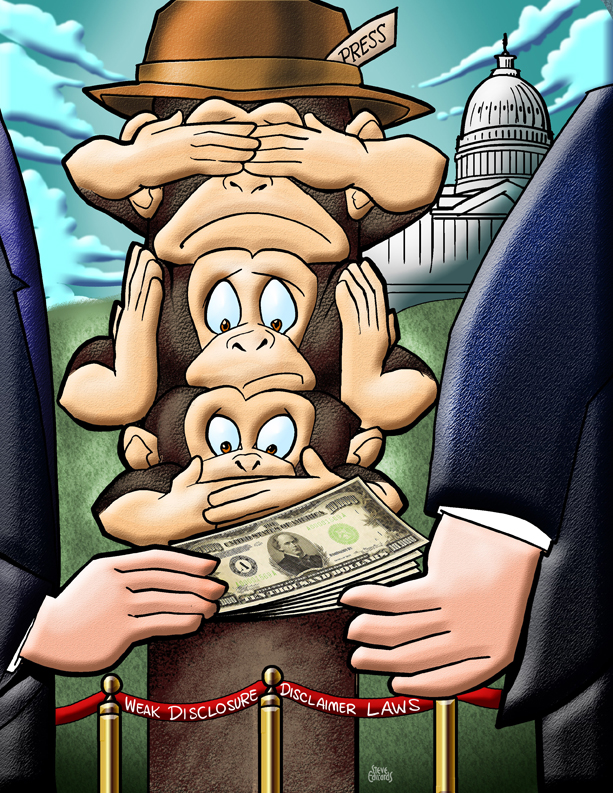

Not so in the United States, where transparency advocates are having a tough time gaining access to Much of this new attention is because of the 2010 Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission case, in which a conservative Supreme Court overturned past precedents and created new First Amendment protections for corporations. While the decision is more well-known for its holding that corporations can spend general treasury funds on election ads, the Supreme Court also ruled that laws requiring donors to file FEC reports – as well as requiring advertisements to indicate who paid for them – do not violate the First Amendment rights of speakers.

“With the advent of the Internet, prompt disclosure of expenditures can provide shareholders and citizens with the information needed to hold corporations and elected officials accountable for their positions and supporters,” Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in the majority’s decision in Citizens United. Justice Clarence Thomas was the lone dissenter, citing instances of threats against contributors to hotly contested political campaigns such as Proposition 8 in California to justify the need for donor anonymity.

Despite the Citizens United ruling, the future strength of disclosure and disclaimer laws is threatened.

In the last year, several organizations have filed federal lawsuits to strike down state and federal disclosure statutes as well as FEC disclosure regulations, while the IRS is under assault for scrutinizing whether certain nonprofit corporations were properly classified as non-political, and thus exempt from disclosure laws.

One problem is that it’s too easy to circumvent current disclosure laws and regulations.

Outside spending on elections – money not directly affiliated with a candidate or political party – has skyrocketed. Since the Citizens United decision in 2010, outside spending through SuperPACs and other independent expenditure organizations increased by 245 percent in the presidential elections, 662 percent in House elections and 1,338 percent in Senate elections, according to election-law expert Richard L. Hasen. Some estimates suggest that some 40 percent of this independent money is non-disclosed.

Comedy Central host Stephen Colbert showed just how easy it is to create a “shell” corporation to funnel non-disclosed money from donors to advertisements. It took attorney and campaign finance reform advocate Trevor Potter just five minutes to show how Colbert could create a SuperPAC that can keep its donors secret and use vague names that don’t give voters a real understanding of who’s behind the ads.

“Various people say, ‘Well, the identity of the group running the ads is disclosed, so what is it you want?’ Well sure, Americans for a Better Tomorrow, Tomorrow (Colbert’s organization) is disclosed as that, but it doesn’t tell you anything,” says Potter, a former FEC commissioner.

Meaningful disclaimers are important for voters, says Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause New York.

“I believe that the public is looking for signifiers in an overly crowded information marketplace,” Lerner says. “Information regarding the major funders of the communication, depending, of course, on who they are, is a signifier, which the public can use. So if it is advertising that is supporting a particular position regarding the environment, and it’s coming from Exxon Mobil, or GE, or Entergy, or Chesapeake Gas, then I’m going to evaluate it in a different way based on what’s important to me, than a communication which comes from the Sierra Club or the League of Conservation Voters.”

Adam Skaggs, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, says weak disclosure requirements also leave voters in the dark about key connections between donors and politicians.

“You can wonder in which direction the causal relation is, whether people are giving money to people they agree with or if people are shaped by the money, but I don’t think that the direction really matters,” Skaggs says. “There’s a conversation going on that is really shaping the way that the democratic process works, and that’s information that voters, reporters and people working at nonprofits should be able to have access to so they can try to help people understand what’s going on.”

But getting these facts into meaningful context and into the hands of voters is harder than one might think.

The Sunlight Foundation and the Center for Responsive Politics, two open-government groups based in Washington, D.C., both struggle with inaccurate FEC information, delayed IRS filings, filings that are messy and nonstandardized, and lack of data critical to tracking where money is coming from and going to, including lobbying data.

Sometimes the money is so well hidden that watchdog groups must rely on accidents to find out where it’s going.

Robert Maguire, researcher at Center for Responsive Politics, says that happened last year, when insurance company Aetna “accidentally” told shareholders about $7 million in donations to the American Action Network and the Chamber of Commerce.

“They were saying that they were supporting health care reform and working with the administration, and at the same time they were giving millions of dollars to organizations that don’t disclose their donors and were pretty viciously attacking anyone who supported reform,” Maguire says.

Advocates see glimmers of hope at the local and state levels where disclosure and disclaimer laws have been expanded. The federal courts also have rejected challenges to disclosure and disclaimer laws thus far. But at the federal level there is little political will to change to the status quo. As Rosenberg points out, what Sunlight, CPR and other organizations are really doing is “laying the groundwork for the next scandal, because that’s when something is going to happen. campaign donations and lobbying activities.