Another side of protests: Small peaceful gathering in Waco

The protest that I covered in Waco, Texas on Sept. 23 was nothing like the large, occasionally violent ones held in other regions. More than 50 people attended and no one was tear-gassed or arrested. I saw only a couple of counter protesters actually approach the group, screaming “Do you know the facts of the case? Breonna Taylor was a drug dealer!” But they left quickly as they were far outnumbered by protesters. They were also the only two people I saw who weren’t wearing masks. (By the way, Taylor was not a suspected drug dealer.)

Grassroots protests such as the one I attended are actually more common than the occasionally violent ones you might hear about. The demonstration was organized by “three angry students” from Baylor University. They were unaffiliated with local Black Lives Matter chapters and other civil rights advocacy groups. The students organized the protest the same morning, when an officer who was involved in Breonna Taylor’s case was indicted on charges of “wanton endangerment.” for bullets that landed in a neighboring apartment.

One of the protest organizers held a sign with a QR code to check attendees’ voter registration and register to vote. She walked around, addressing almost every group of people who had attended together, asking them if they needed help with their registration.

The organizers encouraged participants to download the app “5 calls,” which provides shortcuts to call local legislators. Protesters called Texas senators and urged them to vote to end qualified immunity that limits police accountability and no-knock warrants like the one police were enforcing when they used a battering ram to break into Taylor’s apartment, prompting the gunfight in which she was killed. Organizers had signs with a script telling protesters how to address the senators and make their case.

Even though it was hosted by three students with no structural support in planning, the protest was well organized. The protest’s flyer, which was posted online a few hours before it was held, listed many safety measures in place to ensure the gathering stayed peaceful.

Some of the precautions included prior notification to local police units of the protest and its intention, restricting protesters from blocking sidewalks, the street and driveways and careful consideration in signage wording.

The peaceful nature of the gathering was orchestrated, and the students who put it together expertly diffused any small situations that arose, including the two men who infiltrated the crowd yelling defamatory statements about Taylor. The protesters responded in a calm, assured manner when people walked or drove by jeering at them.

The crowd’s demeanor was productive anger. They lamented Taylor’s death and focused their energy on police reform. Protesters were unsurprised about the indictment, but expressed sorrow and disappointment that no officer was indicted for Taylor’s death. The crowd included Black people and other people of color, but there were also a lot of white allies. I felt compelled to attend this protest as a white journalist because small, peaceful protests aren’t widely discussed, and I wanted to add them into the protest narrative of this year.

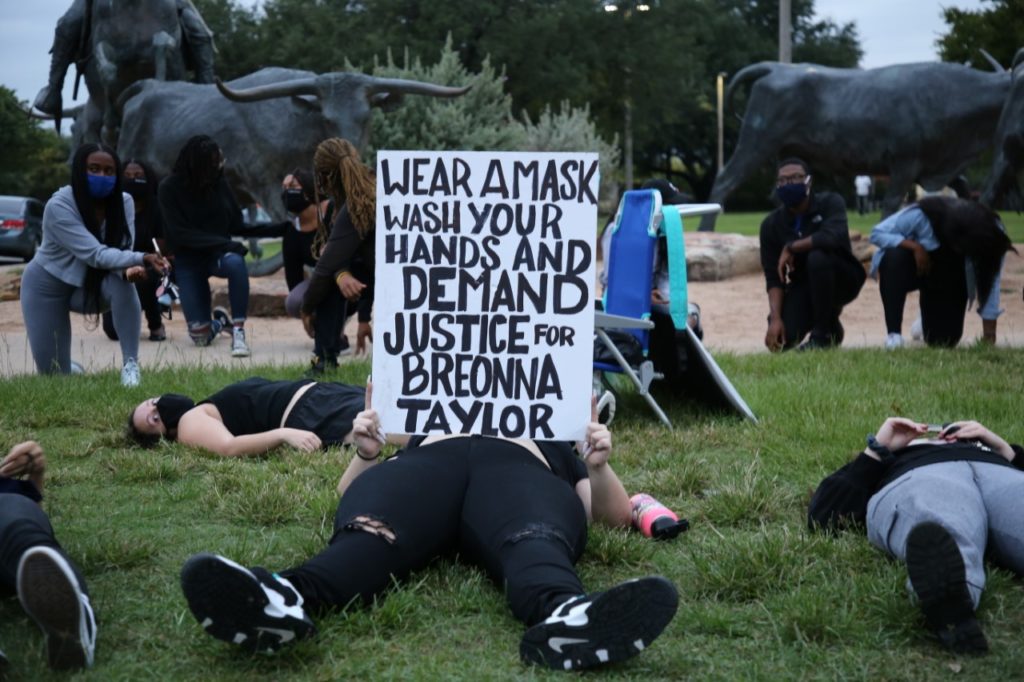

After the voter registration, calls to senators and Black Lives Matter chants, protesters observed five minutes of silence and reflection while lying on the ground or kneeling, to imagine what it must be like to be a Black person in America fearing police brutality.

Near the end of the gathering, the organizers asked if anyone wanted to step up and address the group with their thoughts on Black Lives Matter, experiences with police brutality or anything else they wanted to say. When no one stepped up, the organizers provided encouragement and understanding. They said they were empathetic to the exhaustion faced by Black people being asked to explain their experiences with racism on a daily basis, and they emphasized that the most important product for protesters to leave with was knowing they were cared about and listened to. After the protest, one of the organizers, Brittany LaVergne, offered rides to attendees so they wouldn’t have to walk home in the dark.

Meredith Howard is a student journalist at Baylor University. She can be contacted at meredith_howard1@baylor.edu.