The broken heart of America: A review and fact-check

In “The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States,” Harvard University professor Walter Johnson has written a history of St. Louis that could not come at a more sensitive moment. Between its author’s prestigious pedigree and its exquisite timing, the book is winning a large audience, including many well-intentioned St. Louisans eager to gain a better understanding of their city’s often tragic history.

It is therefore all the more disappointing to report that the book cannot be considered reliable. It is, in fact, shockingly unreliable.

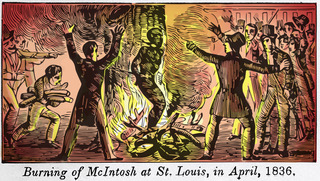

Broken Heart is in one sense valuable in spite of its defects. Given Americans’ ignorance of their own history, and perhaps especially of their own communities’ histories, almost any new survey of our past is welcome. And readers will learn a lot from this well-written book. How many people know, for example, that one of if not the first public lynching in America took place in downtown St. Louis in 1836? That for many years before the Civil War it was actually illegal for free blacks to emigrate and settle in St. Louis? That because of the presence here of Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis was essentially the headquarters for the Army’s battles against the Native Americans and conquest of the West? And much, much more.

Yet Broken Heart has larger aspirations than a mere recounting of the awful things that happened here. It argues for St. Louis’s national significance. St. Louis, Johnson writes, has been “the city at the heart of American history.… the crucible of American history … much of American history has unfolded from the juncture of empire and anti-Blackness in the city of St. Louis.”

This is not to say St. Louis is “unique,” Johnson said in an interview this past spring on St. Louis Public Radio. But “the history of the United States was made, was articulated, was best expressed and first expressed in St. Louis.”

And St. Louis, he said in that interview, is “extreme” — a feature, he argues, that can be seen on both sides of the political dynamic. Although racism and the forces of capital have nearly always dominated, there have also been breathtaking moments of radicalism, he writes — sometimes even interracial radicalism, such as in 1877, when the first general strike in the nation’s history united Black and white workers in what historians sometimes call the “St. Louis Commune.”

Driving both extremes, Broken Heart contends, has been “racial capitalism: the intertwined supremacist ideology and the practices of empire, extraction, and exploitation. Dynamic, unstable, ever-changing, and world-making.” The book is essentially a telling of St. Louis’s history and its impact on the nation’s history through the lens of racial capitalism.

Which leads us to ask, of course, whether this lens gives us the clear picture we so desperately need, perhaps especially now.

***

Nicolas Lemann, in a review in The New Yorker, expresses a degree of skepticism. Broken Heart “demonstrates both the power of the model [of racial capitalism] and its limitations.” The book works racial capitalism too hard, he argues, as an explanatory paradigm for the nation’s and St. Louis’s history.

Someone with Lemann’s deep background in American history and historiography has the credentials to make such judgments. I do not. So I approached the book in the one way that’s natural to a one-time reporter like myself: I fact-checked it.

What I found, to my mounting astonishment, was a litany of errors, omissions, and distortions. And because nearly all of these errors and distortions serve the same apparent purpose – to exaggerate, dramatize, over-simplify and villainize – one has to conclude that Broken Heart is at least as much polemic as it is history.

What follows is a discussion of some of the more egregious examples. Some are central to the thesis; some are not. But when it comes to error, as any reporter or lawyer knows, the smallest can erode trust as much as the largest. In any case, here is a partial accounting, with the topics presented generally in the order they appear in the book:

Slavery – “The deeper truth,” Johnson writes, “is that slavery in St. Louis was uniquely precarious, and because it was uniquely precarious, it was uniquely violent.”

Johnson makes several intriguing arguments to advance his case that slavery in St. Louis uniquely precarious, but the more important part of this statement — the assertion that slavery was “uniquely violent” in St. Louis — is, of course, remarkable. That’s because: 1) the word “unique” is so extraordinarily powerful and 2) making reliable comparisons in an area so difficult to measure as the violence of slavery is obviously nearly impossible. Yet Johnson seems to rest this extraordinary claim on only a few slim reeds: accounts by two or perhaps three women slaves of their own experiences and a memoir by William Wells Brown, an African American writer who wrote, “no part of our slaveholding country is more noted for the barbarity of its inhabitants than St. Louis.”

J. Neal Primm, in his authoritative 1980 history of St. Louis, “Lion of the Valley,” offers this contrasting assessment:

“The local tradition that slavery was comparatively mild in St. Louis was shared even by such moderate or strongly anti-slavery leaders as J.B. C. Lucas, Frank P. Blair, Jr., and William Greenleaf Eliot, who spoke of the humaneness of local masters and the general disapproval of ‘unnecessary’ cruelty.”

Primm cites support for this “local tradition”:

“Manumissions (freeing of slaves by their owners) were more frequent in the city than in rural areas, especially by those who thought slavery was damaging the economy or who favored ‘colonization,’ or both. Blair, William P. Mason, and others of this persuasion freed their slaves in the 1850s, emancipation reaching a peak of 49 in 1860.… Slaveowners illegally helped or encouraged their chattels to learn to read and write; some bondmen were permitted to ‘hire themselves out’ so they could buy their freedom; and slaves were guaranteed trial by jury.”

“Yet,” Primm adds, “there were witnesses who scoffed at the vaunted benevolence of the system. William Wells Brown, an ex-slave, wrote that St. Louis was noted for its barbarity; and there were examples of extreme cruelty, such as hanging a woman slave by her thumbs while flogging her.”

Primm’s conclusion: “Even if the questionable premise that the institution was comparatively humane in St. Louis is accepted, the essential condition of slavery remained.”

Abraham Lincoln – Consistent with his thesis that there is a through-line between the history of America’s treatment of Native Americans and its treatment of Blacks, Johnson writes that Lincoln’s “political roots had more to do with the Black Hawk War than they did with the Black freedom struggle, and his political base lay in the free-soil wing of the Republican Party: antislavery, white supremacist, imperialist and removalist.”

In this connection, Johnson discusses an uprising by Dakotas in what is now Minnesota, after bureaucratic delays in paying the Indians after they had ceded most of their land left them desperate and near starvation. Hundreds of whites were killed. The U.S. Army went to war in response and eventually took a large number of Sioux as prisoners. A military tribunal then tried 392 for murder and sentenced 303 to death.

Here is how Johnson reports what happened next:

“On the day after Christmas in 1862, a week before he signed the Emancipation Proclamation, Abraham Lincoln ordered the simultaneous execution by hanging of thirty-eight Dakota men, in an exemplary act of retribution that remains the largest mass execution in the history of the United States (as well as a marked contrast from the emergent laws of war that governed the treatment of Confederate prisoners of war).”

Now here is Lincoln biographer and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner David Herbert Donald on this episode:

“As soon as the news [of the Indian trials] reached Washington, in mid-October, the President told Pope [the General in charge of military operations against the Dakotas] to stage no executions without his sanction. To gain further information … he also sought the advice of Episcopal Bishop Henry B. Whipple, who advised ‘a new policy of honesty was needed’ for dealing with this ‘wronged and neglected race.’”

In November, Pope warned Lincoln that if all 303 condemned by the tribunal to death were not executed, white Minnesotans would respond with an indiscriminate massacre of the Dakotas. But Lincoln “refused to be stampeded.” He personally read the record of every single one of the 303 condemned men, “…seeking to identify those who had been guilty of the most atrocious crimes … He came up with a list of thirty-nine names, which he carefully wrote out in his own hand: ‘Te-he-hdo-ne-cha,’ … and so on. Wiring the list to the military authorities, he warned the telegraph operator to be particularly careful, since even a slight error might send the wrong man to his death.

“On December 26 the thirty-eight men (one more man was pardoned at the last minute) were executed – the largest public execution in American history. Few praised Lincoln for reducing the list of condemned men. On the contrary, his clemency lighted a brief firestorm of protest in Minnesota, … [and] in [the election of] 1864, Republicans lost strength in Minnesota. Senator (formerly Governor) Ramsey told the President that if he had hanged more Indians he would have had a larger majority. ‘I could not afford to hang men for votes,’ Lincoln replied.”

In short, Lincoln’s “ordered” executions actually represented his accedence to those executions and came in the context of a humane and politically courageous rejection of more executions.

Does this matter? Are these mere details? Didn’t Lincoln still preside over a country that committed ethnic cleansing and a near-genocide against the Native Americans?

Yes, he did, and that part of our country’s record – and Lincoln’s part in it – can never and should never be whitewashed. But by omitting this part of the story, Johnson gives us, at the very least, a distorted picture of the 16th President. He leads us to think that Lincoln’s vaunted humanity was nowhere to be found when it came to Native Americans.

Which was not so.

Ulysses S. Grant – Johnson offers the 18th President a drive-by sliming similar to the one he accords Lincoln.

Grant, he writes, “resigned from the Army in 1854 and returned to farm his wife’s property (and oversee her family’s slaves) in St. Louis County, south of the city. Grant was an indifferent farmer, and in 1860 he quit altogether and moved with his family to Galena, where his father had offered him a job and a regular income in his tannery.”

Johnson is obviously justified in injecting a reference to Grant’s management of his in-laws’ slaves during this period, even though it’s a little off-point: His main criticism of Grant relates to the “murderous fury” he later displayed in the Civil War. But given that Johnson raises the subject of Grant’s relationship to slavery during his St. Louis years, one might expect a fuller account.

At some time during this period Grant acquired a slave, a fact Johnson doesn’t mention although it works against the future 18th President. The likelihood is that Grant was given or purchased the man from his father-in-law. In any case, in 1859 — at a time of financial hardship for the Grant family, when the sale of his slave might have brought $1,000, the equivalent of more than $30,000 in today’s dollars — Grant freed him.

Perhaps this is why Johnson doesn’t mention the man in the first place; perhaps not. In any case, the real story is once again more complex than Johnson is interested in or willing to tell us.

Lincoln Steffens and St. Louis’s Municipal Corruption – In 1902 and 1903, the great muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens published two articles in McClure’s Magazine about the comprehensive corruption of St. Louis’s government. The articles were part of a series by Steffens entitled “The Shame of the Cities,” and dealing with Chicago, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and New York in addition to St. Louis.

One of the central characters in both of Steffens’ St. Louis articles is Joseph W. Folk, the city’s incorruptible and fearless circuit attorney, who almost single handedly pulled back the curtain on the city’s corruption.

Johnson writes:

“Over the course of several years beginning in 1904, Folk investigated a rolling set of conspiracies between local businessmen, bankers, and political leaders to buy and fix virtually every matter that came before the St. Louis city council.… The occasion for Folk’s crusade was, as Steffens noted at the beginning of his first essay in McClure’s, the city’s bid to host the 1904 World’s Fair …”

“The Shame of the Cities” is still in available in print and can even be found online. It takes only a few keystrokes to learn that Johnson has misreported the facts.

Folk did not begin his investigations in 1904. He began, Steffens says, as soon as he took office, which was either in the year of his election, 1900, or the next year – that much is unclear. Regardless, to suggest 1904 is absurd on its face, because Steffens’ essays – which are all about Folk and his investigations — were published in 1902 and 1903.

Moreover, Steffens did not note at the beginning of his first essay in McClure’s that Folk initiated his crusade in connection with the city’s bid to host the World’s Fair. Instead, Steffens (who actually only edited the piece; it was written by Charles H. Wetmore, a Post-Dispatch editor) made a cheeky reference to the Fair. Here is the lede:

“St. Louis, the fourth city in size in the United States, is making two announcements to the world: one, that it is the worst-governed city in the land; the other that it wishes all men to come there (for the World’s Fair) and see it. “

Throughout the essay there is no further reference to the Fair, and none of the scandals Folk investigates relate to “the city’s bid to host the Fair.”

Monsanto – One of the many targets of the anger Johnson flashes throughout his book is the St. Louis-based company now part of Germany’s Bayer AG.

“Monsanto,” he writes, “which began during World War I as a producer of the compounded precursors for high explosives, increased its profits a hundredfold before the war ended.” Referring to the decades after World War II, he later adds: “Monsanto, headquartered in Creve Coeur, emerged as the world’s largest chemical company in these years, producing, one after the other, some of the most notorious products in human history: DDT, Agent Orange, and Roundup, the herbicide whose effects are only now coming to light.”

In fact, Monsanto was founded 16 years before the United States entered World War I, in 1901. (If one is inclined to give Johnson the benefit of the doubt, perhaps he knew that – the date, after all, is plastered all over the Internet and in printed sources — and was only trying to say that Monsanto entered the war years in the fashion he describes.)

In any case, the company’s chief product was initially saccharin, soon followed by caffeine and vanillin, and shortly thereafter, aspirin. Henry Berger, the late Washington University history professor, recounts what happened next in his “St. Louis and Empire: 250 Years of Imperial Quest & Urban Crisis”:

When the United States entered World War I, “The War Industries Board imposed rigid restrictions on the use of saccharin for nonmilitary purposes because a vital ingredient in manufacturing saccharin was needed for making munitions. Monsanto was able to make the necessary ingredient as well as other chemical components created for military purposes and benefited from America’s association with the Allies.”

That obviously puts the company’s early history in a different light. In addition, although Berger’s figures for Monsanto’s financial growth during the war are incomplete, the ones he does provide suggest that a 100-fold increase in profit is wildly exaggerated.

Finally, Monsanto was never “the world’s largest chemical company.” It was never even the biggest American chemical company. A check of the Fortune 500 rankings between 1955 and 2015 shows that DuPont was generally three to seven times larger in sales, and that Dow Chemical was at almost all times substantially bigger as well. In 2016, when Bayer announced it would buy Monsanto, its annual revenues were nearly four times larger (see here and here). Monsanto, however, was the global leader in seeds, including genetically modified ones.

Legal segregation – Johnson brings up a notorious ordinance mandating housing segregation in St. Louis at two different points in his book.

In the first instance he writes: “The city also passed its first segregation ordinance at this time, in 1901, forbidding Black St. Louisans, by popular referendum, from establishing a residence on any block that was at least ‘seventy-five percent white.’”

Fifty-three pages later, he sets the date of the ordinance’s passage at February 29, 1916.

The second date is correct. On that day, Johnson writes, “the city of St. Louis became the first in the nation to pass a residential segregation ordinance by popular referendum …. “

This is accurate. It can also mislead, however, because it lacks context. The fuller story can be found in both “Never Been a Time,” a history of the 1917 East St. Louis race riot by Harper Barnes, and in “St. Louis,” a 1977 work edited by Selwyn Troen and Glen E. Holt. In mandating housing segregation, Troen and Holt tell us, St. Louis was “Following the example of such border and southern cities as Baltimore, Atlanta and New Orleans.” Where St. Louis was first, they explain, was in the method by which it passed its ordinance. The vote in St. Louis “was the first issue to have been decided by the progressive reform innovation of the initiative-referendum method for passing local ordinances.” (This, the editors comment, was an irony.)

None of this, of course, gets St. Louis off the hook in this ugly matter, but it does weaken Johnson’s argument that “the history of the United States was made … was first and best expressed … in St. Louis.”

The 1969 Public Housing Rent Strike – In Johnson’s discussion ofthe strike against the St. Louis Housing Authority by tenants of St. Louis’s public housing projects, he writes: “The successful strike was almost entirely led by Black women.… They were supported by virtually every Black activist organization in the city.”

The strike indeed was led by Black women, and they did win the support of St. Louis’s Black activist organizations. However, Ora Lee Malone — the only Black woman whom Johnson names in this account and whose photograph is included in this section – played a marginal role at best; Malone’s historical prominence lies in other labor-related struggles. The Black women who actually did lead the strike, including the late Jean King, the president of the Citywide Rent Strike Committee and the tenants’ most visible spokesperson, are not mentioned. Also omitted are the key roles played by two white men,Richard Baron, the Legal Services attorney who represented the tenants, and the late Harold Gibbons, a Teamsters Union leader here, who organized the Civic Alliance for Housing to forge a settlement.

The rent strike here had national impact. King testified before Congress. The Brooke Amendment — sponsored in the House of Representatives by St. Louis’s own William L. Clay Sr. – soon followed. It capped tenants’ rent obligations at 25 percent of their income and led in turn to federal subsidies for local Housing Authorities, to make up the difference. The strike here also led to the placement of public housing tenants on the Housing Authority board here, an innovation that was then repeated around the country.

Broken Heart, whose subject, once again, is the role of St. Louis in the nation’s racial history, mentions none of these impacts.

Charles “Cookie” Thornton and the Kirkwood City Council Massacre – On Feb.7, 2008, Charles “Cookie” Thornton, an African-American resident of Meacham Park, an African-American neighborhood annexed by Kirkwood in 1991, shot and killed a Kirkwood police officer guarding City Hall before entering the building where a city council meeting was in session. He then shot and killed another police officer, two city council members and the city’s public works director, and shot the Mayor, who later died from complications related to his wounds in conjunction with cancer treatments. Police arriving on the scene shot and killed Thornton.

Thornton was a well-known figure in Kirkwood and Meacham Park and for many years a widely popular one. Broken Heart portrays him as a man driven to extremes by the betrayal of Kirkwood city officials, who harassed him by ticketing him for parking his dump truck on his lawn and similar infractions. By 2008, Johnson writes, Thornton “owed almost $20,000 – a total that is hard to understand as anything other than a massively disproportionate and punitive response to Thornton’s claim (albeit a stubborn one) of a long-standing customary right to do business in the way that he always had.”

Thornton also felt betrayed by the city for another reason, Johnson writes. He had expected to be awarded demolition contracts by the city in connection with a mall development project in Meacham Park that he had long actively supported. “Virtually everyone in Meacham Park thought that Thornton had been promised work on the project in return for his support, including Thornton himself,” Johnson writes.

But in the end, Thornton won no business on the project. He had lost out, Johnson writes, “in a decision that came down to dollars and cents in the pockets of people who cared more about calculating the bottom line than taking the high road. It was then that Thornton began to … descend into the dark cycle of feelings of humiliation, betrayal, anger and fear that led him to the city council chambers on that February night in 2008.”

Thornton’s perceived betrayal, Johnson writes, took place in the context of a larger betrayal by the city of Kirkwood, related to the redevelopment project. The promises the city made about it, Johnson writes, “turned out to be hogwash – or, if not hogwash, a sort of diluted runoff that still smelled like hogwash.…In the end, the mall project destroyed more than half of Meacham Park … A promised eighty-five new houses became six.”

Johnson refers approvingly to the “sensitivity” shown in a St. Louis Magazine report on the tragedy. He doesn’t mention, however, some crucial facts in that report. Most glaringly, as early as 2002, Kirkwood offered complete forgiveness of Thornton’s fines in return for his agreement to stop violating the law. Thornton, however, refused, saying he wanted a public apology from the city. Then former Kirkwood High School principal Franklin McCallie, a friend of Thornton’s, interceded to try to resolve the matter, but “Thornton kept saying ‘No, no, no!’” McCallie later recalled. After four months of futility, McCallie gave up. The city then made yet another attempt to work it out with Thornton, but that too ended in failure.

A 2010 report published originally by the St. Louis Beacon provides other pertinent facts related to the city’s alleged betrayal of Thornton in connection with demolition contracts for the redevelopment project. Thornton didn’t just want some of the demolition work, the report says, he wanted all of it. But Thornton didn’t have the capacity to do all of the work, Kirkwood officials said, and wouldn’t even bid to get contracts. The Kirkwood officials are identified by name in this report and include several African Americans. (Disclosure: William Freivogel, publisher of the GJR, was part of the reporting team that wrote that article).

In regard to the alleged betrayal of Meacham Park, the Beacon article notes that the redevelopment project remains controversial. But it also cites a number of benefits, including $4 million of TIF (tax increment financing) money spent on housing improvements in Meacham Park, $40,000 premiums for displaced homeowners over the St. Louis County appraised value of their homes, and a new park.

None of this can be found in Broken Heart.

Michael Brown – Johnson repeatedly refers to the 2014 killing of 18-year old Ferguson resident Michael Brown as a “murder.” In one reference it is an “unpunished murder.” In the book’s index it is an “execution.” Here is how he tells the story:

“… Officer Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown, who had been walking down the middle of a street near his grandmother’s house. After a short scuffle in the street, Brown ran away. When Wilson shot him, several witnesses later asserted, Brown had his hands raised in the air. Wilson later claimed that Brown, whom he had already shot at least once, had turned around and run toward the officer, even as Wilson kept shooting.”

Many readers will find Johnson’s terminology justified, in spite of two investigations – first by the U.S. Department of Justice, and more recently (and subsequent to the Broken Heart’s publication) by the office of St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Wesley Bell—that failed to lead to charges of murder or any other crime. After all, at the very least, more competent police work might have averted the physical confrontation that ended in shots fired. And there is plenty of reason to believe that racial animus played a role in how the entire tragedy unfolded. (Johnson’s linkage of the story to the tax structure in Ferguson and the St. Louis region – a major theme of this part of his book — is also provocative and praiseworthy.)

But Wilson did allow a physical confrontation to happen, and Johnson’s telling of the story is highly selective. The DOJ report described something far more serious than a “scuffle.” The report supported the officer’s contention that Brown attempted to reach inside his vehicle and grab his gun; indeed, it found “conclusive evidence that Brown’s DNA was on Wilson’s gun.” It also found that Brown struck Wilson in the face, was wounded by a gunshot inside the car, fled 180 feet, suffered no wounds in the back and then moved back at Wilson immediately before the fatal shots.

The DOJ – Eric Holder’s and Barack Obama’s DOJ, it should be noted – also concluded that Brown didn’t cry out “Don’t shoot” and that, if he had his hands up, it was only for a moment before he began moving back toward Wilson. The DOJ said many of the witnesses who told the “Hands up, don’t shoot!” story had repeated what they had heard from neighbors or on the news. Some witnesses admitted they made up stories so they could be part of a big event in their community. The DOJ said the forensic evidence lined up with Wilson’s account and “Multiple credible witnesses corroborate virtually every material aspect of Wilson’s account and are consistent with the physical evidence.”

None of this is in Johnson’s narrative. He dismisses it all in in a footnote, as follows:

“The separate DOJ report on the murder of Michael Brown, on the other hand, is, at best, a legalistic restatement of the extraordinary latitude provided police officers who shoot unarmed people in the U.S. and, at worst, a complete misunderstanding of the full set of circumstances surrounding the shooting.”

Again, he has a point about the constraints around the DOJ’s (and Bell’s) investigations. But if he is going to present one version of the actual events – the part about what some eyewitnesses initially reported – then it is not too much to ask that he report what the DOJ later said about the credibility of those witnesses and the contrasting information obtained from others.

Jason Stockley – Discussing the downtown protests in 2017 over the acquittal of former St. Louis police officer Jason Stockley, Johnson takes aim at then acting St. Louis Police Chief Lawrence O’Toole. With entirely warranted indignation, he reports on the police department’s brutal treatment of the protesters and O’Toole’s obnoxious comments about it. (“… the police owned tonight,” he declared.)

Johnson then adds this parenthetical sentence: “(O’Toole was a finalist for permanent appointment at the end of 2017 but was not hired.)”

He makes no reference to who was hired: John W. Hayden, who is African American, and whose appointment drew near-universal praise at the time.

Kim Gardner and Wesley Bell or, More Precisely, the Absence of Kim Gardner and Wesley Bell – Two of the more significant political upheavals in the St. Louis area in recent years were the elections of Kim Gardner as St. Louis Circuit Attorney and of Wesley Bell as St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney. Both are Black and both have instituted changes in the way the justice system relates to St. Louis’ Black community.

Bell’s election was especially shocking –a stunning upset of the longtime incumbent, Robert McCulloch, whose handling of the Michael Brown case had been widely seen as biased in favor of Officer Wilson. Broken Heart is unsparing of McCulloch in this matter. Johnson writes: “The refusal … of District Attorney [sic] Robert McCulloch … to allow the case against Wilson to go to trial presented the nation with a lurid example of St. Louis-style police impunity.”

Fair enough. What’s strange is the absence of any mention of what came next: the voters’ decision to boot McCulloch in favor of his outspoken critic. Likewise, Gardner’s name is nowhere to be found in Broken Heart. Yet both of these elections (Gardner first in 2016, Bell in 2018) came in time for inclusion in this book, as Johnson acknowledged in his St. Louis Public Radio interview.

The elections of Gardner and Bell might have found their way into the hopeful conclusion Johnson gives his book. Instead, he builds that conclusion on descriptions of various community-improvement efforts by people he himself refers to as “marginal and radical.” Beneath the surface, he writes, “these ordinary people are doing something beautiful and profound.” In the book’s very last sentence, he paints an image of Black children being trained as runners by a woman whose own son was shot to death by a police officer in 2017. “They fly around the track in the fading light, little kids taking impossibly long strides.”

Poetic, for sure. And a case can certainly be made for including such descriptions in the book’s conclusion. But how can these images be allowed to crowd out any mention of the very nonmarginal political shocks represented by the elections of Bell and Gardner? Why aren’t we offered the meat with the meringue?

A Final Word

The basic building blocks of the story Johnson tells are obviously true: Americans did all but exterminate Native Americans; whites have practiced hideous racism toward Blacks from St. Louis’s earliest days; our racist history is built into the fabric, the structure, of our community; and that history continues to unfold. As he writes: “Whether one focuses on tax abatements justified by the inclusion of tranches of Black neighborhoods in the districts drawn on a map, the poverty parasitism of the payday loan industry, the for-profit policing of the segregated cities structured by St. Louis’s past, or the political economy of mass incarceration, the recent economic history of the city provides a series of examples of how to extract wealth from people who have already been pushed to the precarious margin of survival.”

But Johnson’s storytelling is selective, tendentious; for whatever reason, facts that don’t fit his narrative don’t find their way into the story. And at times he’s downright sloppy. The combination destroys the reader’s faith that he is offering us the accurate and nuanced accounting we need.

Trying to explain these flaws would involve speculation, which is always hazardous and usually ill-advised. But perhaps in this case speculation isn’t necessary. Johnson himself seems to offer us an explanation.

In his St. Louis Public Radio interview, the author acknowledged, “A lot of my rhetoric is pretty hot, and I feel pretty hot about a lot of things.”

He is a native of Columbia, Mo., Johnson tells us in Broken Heart’s prologue, and he has visited St. Louis “countless times” throughout his life.

“I came to this book less as a professional historian,” he writes, “than as a citizen taking the measure of a history that I had lived though but not yet fully understood. This is a history that I have resisted, but also a history from which I have benefited, as a white man and a Missourian.”

A zealous attachment to his theory of the case (racial capitalism) as the key to American history, a justified righteous indignation about our nation’s history and misgivings over his own background may have gotten the better of this historian’s professional discipline. Too bad for all of us.

Paul Wagman ( wagmanp@outlook.com ) is a former St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter and FleishmanHillard executive. He is now an independent writer, editor, and public relations counselor.