City of St. Louis ‘betrays’ its pledge to alter legal positions protecting abusive police, critics say

Six months after St. Louis Mayor Tishaura Jones’ administration promised to reconsider its defense of legal doctrines that protect abusive police, it is continuing to defend them, prompting charges of “betrayal” from civil rights lawyers.

In campaigning for office, Jones spoke frequently about the need for greater police accountability, citing the deaths of George Floyd in Minneapolis from a knee on the neck and Breonna Taylor in Louisville from a botched no-knock raid.

Six months ago, St. Louis Public Radio asked the mayor’s office why it still was going all out to defend St. Louis police in similar cases – the death of Nicholas Gilbert in 2015 in a case of prone restraint with six officers on top of his manacled body and the police killing of Don Ray Clark Sr. in 2017 in a no-knock raid on the 63-year-old veteran’s home in Dutchtown.

Jared Boyd, the mayor’s chief of staff, said then that the city would reconsider its legal positions and that the new city counselor would take a new look at “what winning looks like…It’s not to say we shouldn’t be cognizant of city resources, but that can’t be the only thing” as it has been traditionally, he said.

Those words have been thrown back at the mayor’s office in recent days by civil rights lawyers, by two of the town’s best-known columnists, Tony Messenger of the Post-Dispatch and Ray Hartmann of Riverfront Times, and by the host of St. Louis on the Air, Sarah Fenske.

Javad Khazaeli, who represented citizens who filed civil rights suits after being abused and arrested during the Sept. 17, 2017 “kettling,” said the word for the city’s inaction was “betrayal.”

Not only is there no evidence of altering the city’s position in the prone restraint and no-knock cases, but the city is also trying to protect officers who abused citizens during the much-criticized mass arrest on the evening of Sept. 17, 2017 during protests that followed a judge’s acquittal of former officer Jason Stockley in the killing of Lamar Johnson after a high-speed chase.

Khazaeli says the city is seeking a national precedent expanding the use of the doctrine of qualified immunity in mass arrest situations.

Qualified immunity already is the leading roadblock to police accountability, acting as a get out of court free card for officers who violate citizens’ civil rights.

It’s actually better than a get out of court free card. It’s a never come to court card. The case is thrown out before ever going to trial.

If an officer’s conduct does not violate clearly established law, the officer is immune from lawsuits. The only conduct that does violate “clearly established law” is an action that “every reasonable” police officer would know was illegal the moment it occurred. That may require a prior Supreme Court decision involving almost identical facts.

The city lost on qualified immunity in the kettling case in January before a three-judge panel of the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in an opinion written by a judge appointed by former President Trump. Now the city is asking the entire 8th Circuit to meet en banc to overturn the panel decision.

Nick Dunne, a spokesperson for Jones, told the Riverfront Times, that the city “is not and will not make any argument to expand qualified immunity – only to apply existing federal law as it applies to holding individual public servants accountable.” Boyd, the chief of staff who made the promise to reconsider legal positions in police cases, said in an interview Wednesday, that the first thing the city will tell the appeals court if it agrees to hear the case en banc is that the city is not seeking to expand qualified immunity.

But the city’s brief calls the appeals panel’s decision “a dangerous precedent for police attempting to preserve public order in civil disorder situations.”

The brief angles for a new Supreme Court precedent, saying the case “raises questions of critical national importance in the context of policing mass civil disorder.” It seeks a new ruling that would immunize subordinate officers “under the unique circumstances of a mass arrest, during mass civil disorder” – even if their supervisors orders were clearly unreasonable.

The brief does not cite a prior Supreme Court decision exempting all subordinate officers from liability in mass arrest situations. So this would be new law – hence the reason critics say the city is asking the court to expand qualified immunity.

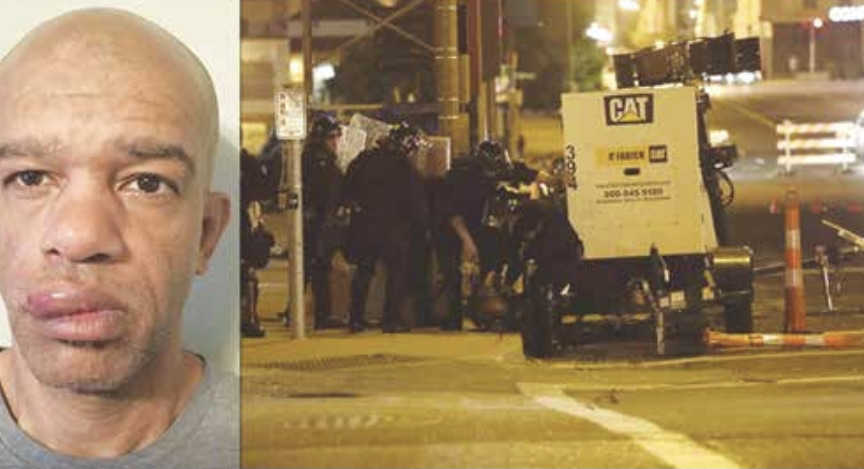

A massive amount of evidence has been assembled showing widespread misconduct in the Sept. 17 kettling arrests. Officers beat citizens, sprayed them in the face with pepper spray and arrested them after trapping a group in a city block near Washington and Tucker Blvd. in downtown St. Louis and refusing to let them leave.

A federal judge made this summary: “Over 100 people were arrested that night. During and after the arrests, officers were observed high-fiving each other, smoking celebratory cigars, taking selfies on their personal phones with arrestees against the arrestees’ wills, and chanting, ‘Whose Streets? Our Streets!’ An anonymous person posted a celebratory photo of police officers on Twitter that night.”

The night of Sept. 17 was the same night that white officers severely beat a Black undercover officer, Luther Hall, whom they mistook for a protester. The beating occurred after the officers had exchanged racist texts expressing their enthusiasm for beating Black demonstrators.

Different critics of the mayor put the blame for failing to alter the city’s legal position on different people. Hartmann, the RFT columnist, says that even though the new city counselor, Sheena Hamilton, is the first Black woman in that post, she has an establishment background with Armstrong Teasdale and Dowd Bennett and has defended major employers against race discrimination suits.

Khazaeli blamed Robert Dierker, the former judge and deputy city counselor, who has supervised the briefs and clearly added signature rhetorical flourishes. Khazaeli told Fenske:

“All I know is that the person who talks to us (Dierker) and who is the brains behind this litigation during this current administration is the same person who titled a chapter of his book, “The Cloud Cuckooland of Radical Feminism.’” The book was, “The Tyranny of Tolerance: A Sitting Judge Breaks the Code of Silence to Expose the Liberal Judicial Assault.”

In the early stages of the Gilbert prone restraint case, Dierker wrote that Gilbert’s mother’s argument to the U.S. Supreme Court was “agitprop” designed to “use published reports regarding the death of George Floyd as a cudgel to try to browbeat this Court into reviewing a case that is a straightforward application of basic Fourth Amendment principles. The only things in common between this case and the reports regarding George Floyd are drug use and heart disease.”

That argument didn’t persuade the Supreme Court, which sent the case back to the 8th Circuit.

Undaunted, Dierker’s response for the city was that the Supreme Court had actually “found no fault” with the 8th Circuit’s decision — even though it had sent it back to the appeals court with an opinion expressing disagreement. Dierker said the appeals court shouldn’t spend any more time on arguments before it “put(s) an end to this case.”

Kevin M. Carnie Jr. of the Simon Law Firm, the lawyer for Gilbert’s mother Jody Lombardo, said the city has not expressed an interest in settling the case, which still is pending before the appeals court.

Emanuel Powell, staff attorney at ArchCity Defenders and a lawyer for the Clark family, said police officers in that no-knock case are also seeking qualified immunity. Powell has been awaiting a decision on pretrial motions since Nov. 19 of last year. He says that the litigation delays can end up denying clients justice. In a separate case involving a death in the Workhouse, the mother of the dead inmate died recently after waiting more than two years for a decision.

“It’s a litigation strategy, he said, “that results in exceptionally long times between the filing of cases and any real work to uncover the truth and get accountability for those impacted by police violence.”

William H. Freivogel is publisher of GJR, a professor of media law at Southern Illinois University Carbondale and a member of the Missouri Bar.